Great Read: Looking back on a child migrant’s journey north on ‘The Beast’

- Share via

Denis taught me how to tame “The Beast.” He was 12. I was 52.

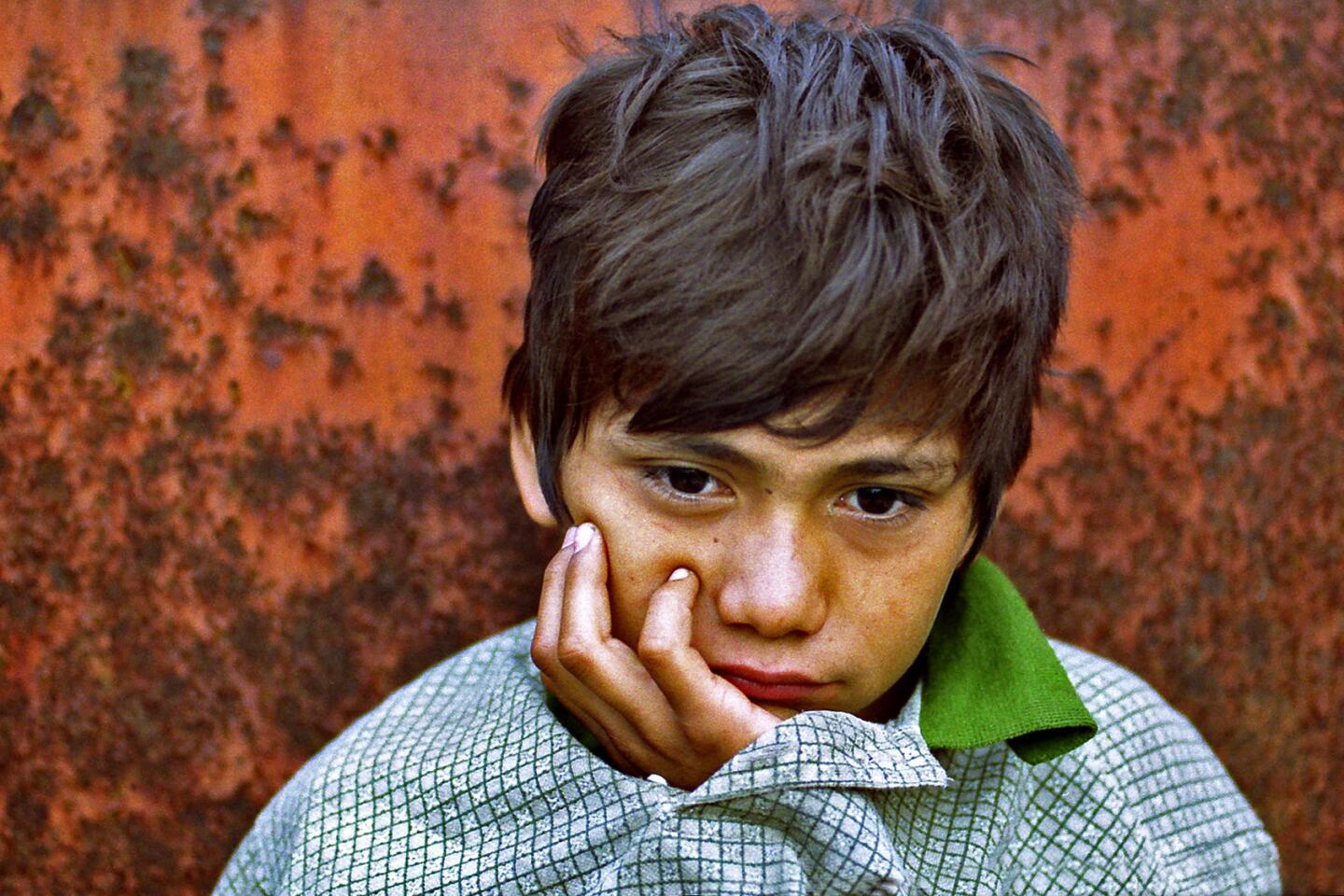

We met in a rail yard in Tapachula, Mexico, not far from the Guatemalan border. I had slung two cameras over my back and climbed the iron rungs to the top of a hopper car. I peered over and saw Denis curled up on a bed of gravel. His mattress was crumpled paper, his blanket an oversize pullover with a green collar.

A single click of my camera startled him awake. He stood up on his mattress. He looked like a kitten stretching and yawning.

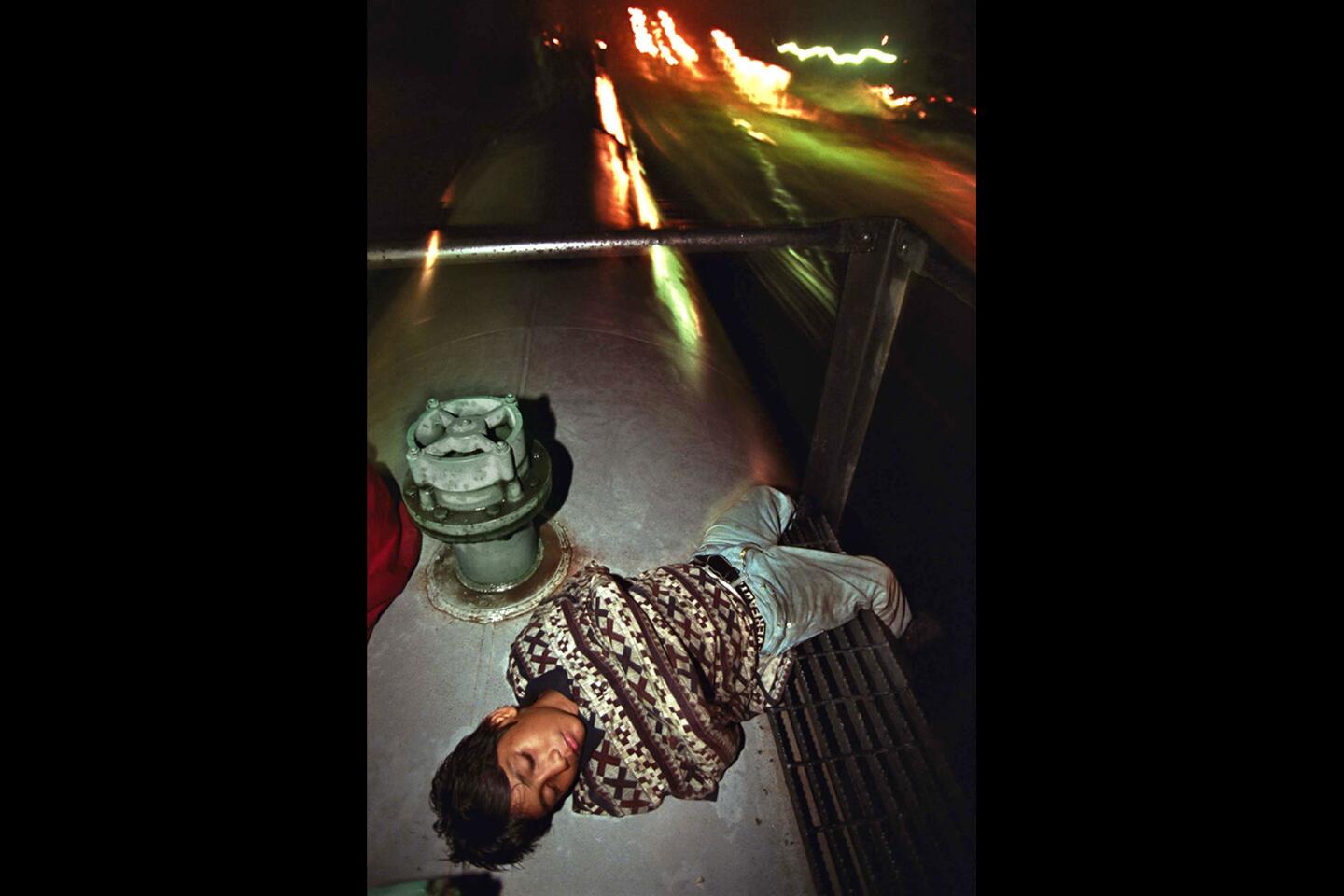

It was the summer of 2000, and I was there to document the journey of the stowaways who rode the freight train that lurched northward through the soggy Mexican countryside. Migrants called it The Beast — a machine that would mutilate those who slipped or carry the lucky ones to El Norte.

Denis — his last name was Contreras — shoved his hand into the pocket of blue trousers that still had a crease down the center of each leg. He yanked out a little matchbox. He slid it open to reveal a few matches, several Mexican peso coins and a folded scrap of paper. He wanted me to read it.

Written on the paper was his mom’s 10-digit phone number.

“I want to see my mother because I don’t know her,” he said. “I want to see her face. She lives in the state of Los Angeles.”

Lesson No. 1. How to jump onto The Beast.

You have to run the same speed as the train. Grab the ladder on the front of the train car. That way if you slip, you can pull your legs off the track before the wheels come. If you grab the ladder on the back end and you fall, the wheels of the next train car are so close they’ll chop off your legs. I’ve seen it!

::

For three months I hung onto, jumped across, crawled over and slept on top of more than a dozen freight trains to capture the experiences of youngsters heading to the border. Working with reporter Sonia Nazario, we produced “Enrique’s Journey — The Boy Left Behind,” a six-part series published in The Times in 2002.

Fourteen years after that journey, I was in Denis’ hometown, San Pedro Sula, Honduras, the murder capital of the world. Another Times reporter and I were doing a story on the sharp increase in the number of Central American minors — tens of thousands of them — who have been crossing the Texas border without their parents. Just like in 2000, many of them are stowaways on The Beast.

We didn’t know anyone in San Pedro Sula, but I had an address.

Before heading to Honduras, I had copied a page from my journal dated Aug. 3, 2000. Denis had carefully printed his address in that journal while we were on a train in Chiapas state.

During that earlier trip, I would track Denis in my viewfinder for a couple of days, lose track of him for a while, and then find him again. I remember thinking how fragile and vulnerable he looked. But the more I focused on him, the more he revealed his disarming street wisdom. He knew how to enlist others to watch over him. He didn’t need me.

But now, all these years later, I wanted to find him again. He had tamed The Beast. Did he wish he never had?

The address was specific: colonia, street, block and lot.

It wasn’t easy to find. We stopped several times to ask for directions, but people seemed suspicious of us. So we drove to the barrio’s police station and found the officer in charge in the dirt parking area.

“Who? Who are you looking for?”

I jumped out of the car and answered, “Denis Contreras.”

Another cop within earshot said, “Any brothers or sisters?”

“Sandra, Mabel, Omar, Edwin.”

“Yeah, I know the house.”

He took the lead on his bicycle. When he stopped, he leaned his bike against the white painted grillwork spanning the entrance and knocked on the iron gate.

The TV was loud so I knocked and yelled, “Hola, Denis?” A twentysomething girl in skinny red pants stared at us from the interior doorway. She looked just like Denis.

Mabel invited us in. Soon I spotted a bare-chested, sleepy-eyed man. I blurted out in English, “Oh my God, Denis, it’s you! Remember me? I’m Don. We rode the trains together!”

Lesson No. 2: How to sprint along the back of The Beast if there’s trouble.

Don’t look down between the train cars. It’ll make you afraid. Just look straight ahead and stare at a spot on the next car where you want your foot to land. Start running as fast as you can along the middle of the roof and jump hard. It’s fun, like freedom!

::

Why were kids risking their lives to leave? In our two weeks in Honduras this summer, we found some answers.

We followed a mother with her 2-year-old son, trying to hire a smuggler to guide them to Los Angeles. Not long ago, her sister was killed in her house by a gangster, and her grieving brother hanged himself in the bedroom.

I photographed a young man who had recently been deported from Texas. He posed behind the razor-wire-topped wall that surrounded his house. Gang graffiti marked the streets. Two days after he had returned from the United States, his traveling companion was killed by a neighborhood gang member at the corner store.

I stood in the rain at the city morgue loading dock where relatives tenderly lowered the doll-like corpse of a 6-year-old girl into a small wooden coffin. She had been caught in the crossfire — shot through the heart by a family member who was in a gang.

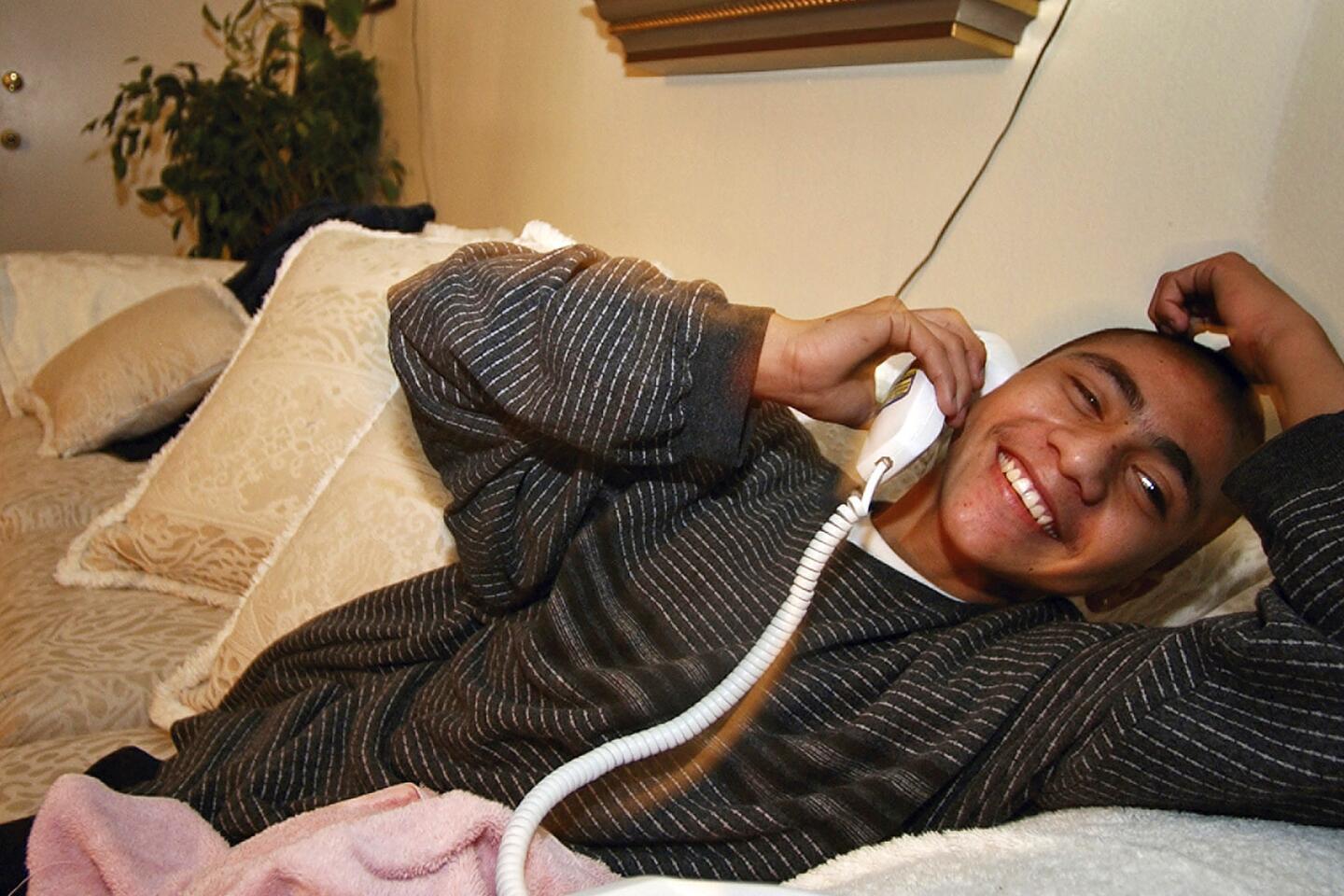

I already knew some of Denis’ history; we had met a few times over the years. He found his mom, in San Diego. He went to school, learned English. But he drifted into trouble, spent time in juvenile hall, and his mom sent him home to Honduras. Then, four years ago, he called to say he was back. We met in La Jolla at his landscaping job; he said he had found religion, gotten a girlfriend and started a family.

But more trouble would follow. In San Pedro Sula, inside the small, dim living room of the home where he was born, he told me that he had been deported just a month before.

As we talked, Denis’ neighbors were squeezing between our car and the gate, straining for a glimpse of the strangers inside.

We stepped into the breezeway between the front door and the gate. Denis posed for a couple of photographs, but he appeared uneasy. “I haven’t been back long enough to know who the bad guys are,” he explained.

Denis agreed to meet me for an interview the next afternoon, but not at his house. “Meet me after work. I’m off at 3.”

Lesson No. 3: How to avoid trouble on The Beast.

I would beg for money and give it to the men on the train to buy cigarettes and Chiclets. I’d smoke one or two a night to help stay warm because it gets cold. I was trembling, like shaking. The rest I’d give away as gifts so they would protect me.

::

The next day, I waited outside a 10-story office building in the Altia Business Park. It looked like Irvine, with its mirrored windows and lush landscaping.

A few days earlier I had spotted a 5-foot-tall poster for the business park at a reception center for deported Hondurans. It read, “You can also live your American Dream in Honduras.”

Denis worked on the fourth floor in an international call center, answering customer complaints from Denver Post newspaper subscribers.

We met near a line of taxis outside the guarded employee entrance. He had always looked sharp, and today was no different. He wore khaki slacks and a polo shirt. But the smile I remembered was missing.

“I’m sorry, Don, I don’t want to talk about anything,” he said. “I just want to forget about everything.”

Lesson No. 4: How to get by on The Beast.

People would give me shirts and sweaters. Every time the train would stop I would go knocking on doors. I’d smile and tell them I was from Honduras and I’m looking for my mother and I hadn’t eaten for a day. They would react friendly and say, “OK, wait right there, I’ll bring you something.” They’d give me some water, beans in a little plastic bag and a handful of tortillas. I didn’t carry anything else but my little matchbox.

::

A few days later, colleague Cindy Carcamo and I wrapped up our reporting and were ready to jet home the following morning. I called Denis and invited him to join us for dinner, and was pleasantly surprised when he agreed.

We picked him up outside the barrio police station, several blocks from his house.

At the restaurant, he scanned the menu. “I’d like fish. I haven’t had fish in years. I couldn’t afford it. I would really enjoy that.”

Carcamo asked Denis what he remembered about me. That brought a smile to our faces and eased us into a long night of good conversation.

Denis recalled that he first laid eyes on me in the Tapachula freight yard. He was the youngest of half a dozen men and boys waiting for the next freight train.

“You were the first white man I’d seen since leaving Honduras,” he said. “Right away I asked you for money because I had a good memory in my head. The last white man I met was when I was 11. I had run away from home and I walked up to him and asked for money. He gave me $10. I couldn’t believe it.

“So as soon as I saw you I hoped I’d get that lucky again. You didn’t give me anything. But you talked a lot and asked a lot questions.”

At the restaurant, he answered all my questions. But he didn’t offer an anecdote that would neatly summarize why Honduras was being drained of future citizens.

“Why did you leave, Denis?” I asked.

He explained that when he was younger, he often ran away from home to escape an older brother who hit him. Each time, his sister Sandra would find him and talk him into coming home. But when he was 10, he heard another boy talking about riding the trains to the United States.

“He said it was fun, it was safe, it was fast. I would just listen, listen, listen. Then my brother hit me again and I decided to go.”

Looking back, he said, he still felt guilty that he had stolen money from his sister’s room to buy the bus ticket to the Guatemala-Mexico border.

“Sandra raised me since I was 1½ years old, almost a baby,” he said. “She was my sister, but she was my mother too. But I just left and didn’t realize it until like four years ago that I broke my sister’s heart.”

He had a tattoo of his sister’s name on his chest, and he named his oldest daughter Sandra as well.

The desk clerk called a taxi to take Denis home to his barrio. As we waited, I asked, “Do you wish you’d never gone?”

He didn’t hesitate. “Yes,” he said.

The taxi pulled up. “But you found your real mom, learned English and got a job,” I said. “That was your dream on the train. Wasn’t that good enough?”

“No.”

I held the back door open and Denis jumped in. “What would you say to those thousands of kids who want to ride the trains to the North now?”

“I would tell them to stay,” he said. “They might get a better life, but if God wanted them to be born in the United States, he would have done that. He decided for us to live right here.”

Lesson No. 5: How to stay alive on The Beast.

I heard about females getting raped, people fighting with machetes. You know, God was with me. An angel was protecting me.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.