Back Story: When India and Pakistan clashed, fake news won

- Share via

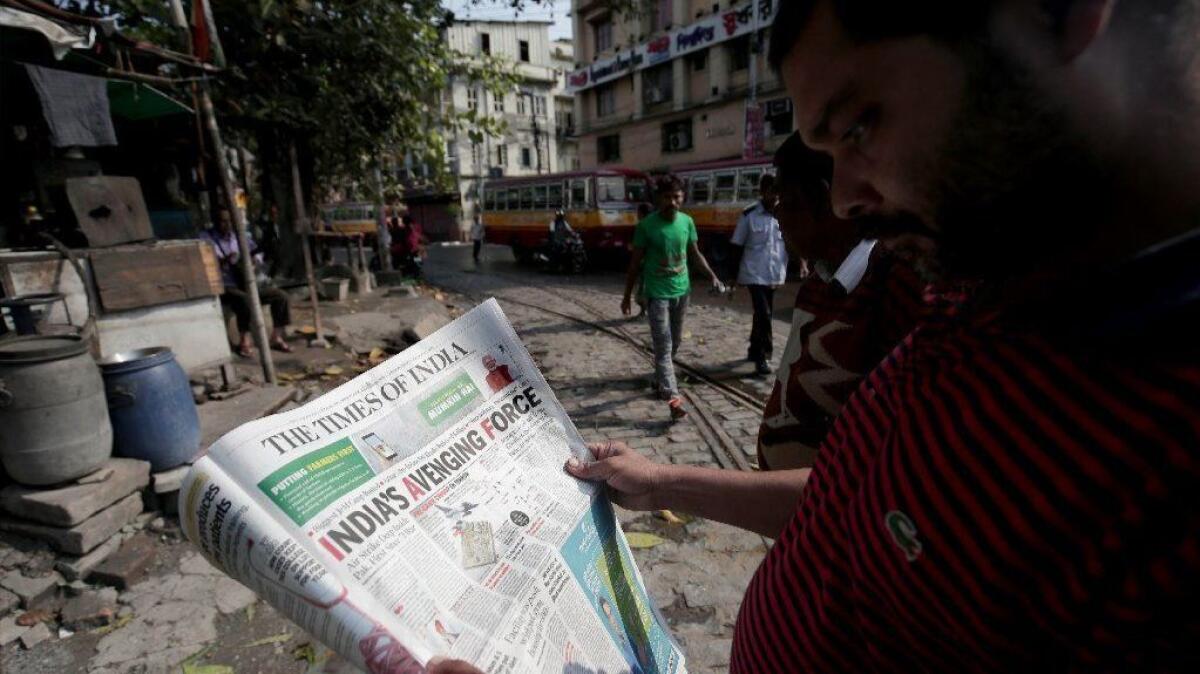

Reporting from Mumbai, India — On Feb. 14, a car bomb hit a convoy of paramilitary police officers in Indian-controlled Kashmir. The suicide attack claimed by a Pakistan-based terrorist group killed 40 officers, and Indian social media accounts were immediately filled with gory images.

But many of the pictures and videos that went viral weren’t from the attack. While the paramilitary force was evacuating its injured and sending the remains of the dead back to their families, a deluge of fake news — doctored and mislabeled — was spreading across India.

One image showed a bucket filled with mutilated body parts, mislabeled as the remains of a dead Indian soldier. A video of an exploding vehicle, purportedly showing the Kashmir bombing, actually originated in Iraq. Another viral video turned out to be of a car bomb in Syria.

With India in the midst of a heated national election campaign, the false and misleading images — sometimes republished by mainstream media — fueled calls for military retaliation against rival Pakistan.

Two weeks after the attack on police in Pulwama district, India bombarded what it said was a Jaish-e-Muhammad terrorist camp deep inside Pakistan, and Pakistan responded by downing an Indian fighter plane and capturing its pilot. Tensions subsided when Pakistan released the pilot, but experts said that fake news had helped bring the two nuclear-armed neighbors close to fighting another war.

“The wave of misinformation after the Pulwama attack was driven by inflamed emotions, overanxious media on all sides, the desire to use this as a political weapon,” said Govindraj Ethiraj, a journalist who runs the Indian fact-checking site Boom.

“Fake news is the manifestation of accelerated information dissemination,” he said. “In Pulwama, this has gone to a new high.”

India has seen a burgeoning industry of fake news and misinformation, driven by the proliferation of smartphones and the popularity of WhatsApp, the Facebook-owned messaging platform with more than 200 million users in India.

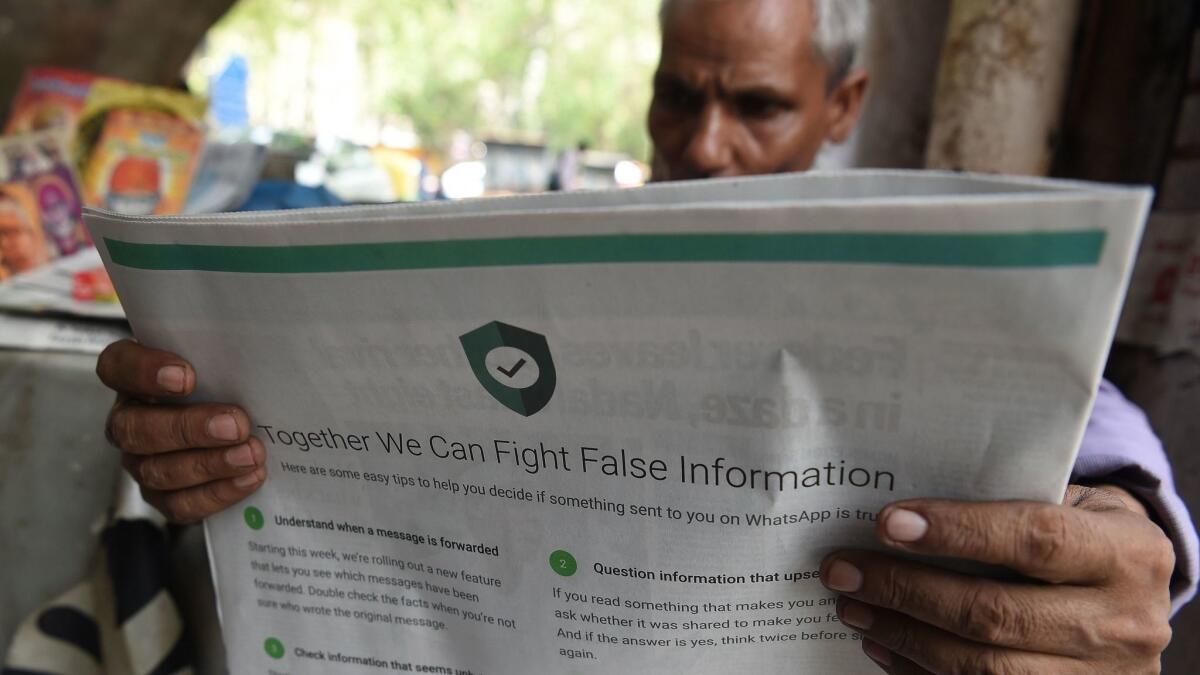

Politicians have blamed WhatsApp, and Indian regulators have warned social media companies that they must take down false and unlawful information or face legal action. WhatsApp has responded by limiting the size of chat groups and the number of times one message can be forwarded; it also launched a public education campaign in India to curb the spread of fake news.

How WhatsApp is battling misinformation in India, where ‘fake news is part of our culture’ »

But the barrage of misinformation after the Feb. 14 attack in Kashmir suggests that these efforts are not enough.

“Maybe these steps have reduced [misinformation], but the scale of this event is so large it could well be counter-balancing the impact of these fixes,” Ethiraj said.

A viral video showing fighter jets destroying a target, purportedly the Indian air force’s Feb. 26 airstrike, turned out to have been taken from a video game. A video posted as showing military personnel celebrating after the airstrike was actually year-old video of Indian army soldiers dancing. A photo labeled as an Indian soldier reporting for duty despite being injured really showed a wounded Russian soldier.

Credible mainstream television channels even picked up false social media posts and presented them as facts. On Feb. 26, several Indian media outlets showed old footage of a Pakistani jet and incorrectly identified it as having been taken that day.

Many of the posts were overtly political. A doctored image purported to show Rahul Gandhi, president of the opposition Congress Party, standing next to Adil Ahmed Dar, who had claimed to be the suicide bomber. A doctored video of Congress leader Priyanka Gandhi Vadra claimed to show her laughing at a news conference after the bombing. A photo taken out of context showed Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi posing for cameras instead of paying tribute to the slain paramilitary officers.

Many of the fake posts were easily debunked. But experts said they fed into many Indians’ jingoism and political partisanship.

“During such a time, when people’s sensitivities are involved, people are more vulnerable and gullible,” said Pratik Sinha, co-founder of Alt News, an Indian website that aims to debunk fake news. Sinha said his site’s traffic increased by more than five times on the day of the Indian airstrike.

Why the next round of India-Pakistan hostilities could be even scarier »

The effect of fake news was exacerbated by a lack of details from the Indian government and conflicting accounts provided by India and Pakistan.

The Indian air force did not confirm details or casualties of its Feb. 26 airstrike. But the Indian foreign secretary said the strike killed “a very large number” of terrorists, and Amit Shah, president of Modi’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party, claimed that more than 250 terrorists were killed.

Pakistan said there had been no casualties or damage to infrastructure.

As the election campaign heats up, with voting in multiple stages set to begin in April and results expected May 23, the Election Commission of India has raised concerns about the effect of fake news. Facebook has said it is expanding its fact-checking network in preparation for the elections.

Even the Indian military has begun to fight fake news.

As false images went viral in February, India’s Central Reserve Police Force, whose soldiers were killed in the initial attack, asked Facebook and Twitter to block such content and issued an advisory on Twitter asking people to refrain from circulating unverified images.

“This was false and very disrespectful of the sacrifices made by the soldiers,” M. Dhinakaran, a CRPF spokesman, said in an interview. “During such a sensitive time it had the potential to create communal tension and lead to violence.”

The day after the attack, the CRPF set up a team of 12 soldiers to fact-check the deluge of fake posts. They asked their force of 300,000 soldiers spread across India to identify misleading posts, which were fact-checked at headquarters, and to speak up in their private WhatsApp groups to correct misinformation.

“With traditional media, we could control the spread of fake news by giving them the correct picture,” Dhinakaran said. “But with social media controlling the message, it is harder.”

The elaborate ceremony that says everything you need to know about India-Pakistan tensions »

In the days after the attack, the team said, it debunked about 20 stories. Some verged on the absurd — including a photograph of a puppy accompanying a false claim that 13 trained sniffer dogs had been killed in the blast.

Some of the doctored images shared were so gory that members of the CRPF team erased them from their computers and phones.

“It was really heartbreaking,” said one team member who requested anonymity because he wasn’t authorized to speak to the media. “Forty of our martyrs had laid down their lives for the integrity of the country. If hatred was being spread in their names, we thought that this defeats the purpose. So we decided to counter it.”

Weeks later, politicians in both India and Pakistan are sticking to their stories about the various attacks. Pakistan’s media have also carried unsubstantiated claims. On Feb. 27, Pakistani mainstream media outlets showed a 2016 image of a crashed Indian jet and claimed it was taken that day.

“The fact that both governments have effectively been able to create these information bubbles, where it seems like most of their citizens believe the official version, paradoxically creates room for de-escalation,” said Sadanand Dhume, a resident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute who writes about South Asia.

“Everybody’s willing to believe their own version, which means that both sides can declare victory to their people and go home.”

Thirani Bagri is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.