Must Reads: ‘I want this day to heal me’: For thousands, the canonization of Oscar Romero was deeply personal

- Share via

Reporting from Vatican City — In life, Archbishop Oscar Romero of El Salvador was persecuted, shot in the heart by a single bullet while he celebrated Mass.

In death, his legacy was politicized, calumniated — all but silenced.

So for many Sunday, it was extraordinary to see Pope Francis at last declare Romero a saint in St. Peter’s Square.

Tens of thousands of pilgrims filled Vatican City’s ancient plaza for the ceremony, which also canonized Pope Paul VI, who led the church through turbulent times in the 1960s.

Romero’s followers traveled from El Salvador, Los Angeles, Washington; from distant lands like Sweden, Norway and Australia.

On this grand stage, they savored every detail: the bright blue sky filled with cotton-like clouds; the Gregorian chants ringing over a sea of 70,000 people; the red-ostrich-feathered helmets of the Vatican’s fancy Swiss guards; the bloodstained rope belt worn by Romero at his time of death, now tied around the Pope’s waist to honor his memory.

Romero! Romero! Your pueblo is with you, Romero!

For a people who endured the atrocities of war, the oppression of poverty, the agony of gang violence — and a long, complicated history with the United States that lingers more than ever — this canonization was not only a celebration. It was redemption.

Redemption for a saint whose assassins have yet to be brought to justice in his homeland.

“We deserved to have this day,” said Jesus Gutierrez, a Salvadoran doctor from Torrance who waited before dawn to enter the square. “We’ve dreamed about being right here, in this moment, for so long.”

A great pilgrimage

To reach Rome, some went to great lengths. They took out bank loans and loaded credit cards; they crowdfunded and dipped into savings; they worked double shifts and lived on tight budgets.

“I sold pupusas, empanadas, panes con pollo, yuca frita, mangoneadas,” said Norma Portillo, 52.

The morning of the ceremony, the teacher was decked out in El Salvador’s blue and white colors. She worked up a large crowd from her hometown, Ciudad Barrios, where Romero was born in 1917.

“Que viva Romero!”

“Que viva!”

Everywhere you turned there were people with firsthand stories about their soon-to-be saint.

He baptized me during a Mass in San Salvador.

He held my daughter in his arms when he visited Santa Tecla.

He had dinner at my Tia Conchita’s house when he passed through San Miguel.

Antonia Estrada Posada, 68, struggled with a different kind of memory as she held fast to the guardrail encircling the growing crowd outside St. Peter’s Square.

The last time she was among thousands of people was in 1980 for Romero’s funeral. She was 30.

El Salvador was in political shambles then, on the brink of war. Military death squads backed by U.S. forces were killing countless people. Nearly all of them were poor. Romero was assassinated — for being one of the fiercest critics of the massacring.

Romero, the country’s archbishop, spoke out against the systematic killings of the poor by the right-wing squads that did the bidding of the country’s military-led government. By 1980, the country had descended into civil war, and Romero’s voice came to be a galvanizing force for the resistance, the loosely organized groups that pushed back against the oppression. Others, the government in particular, regarded him as a leftist, an agitator.

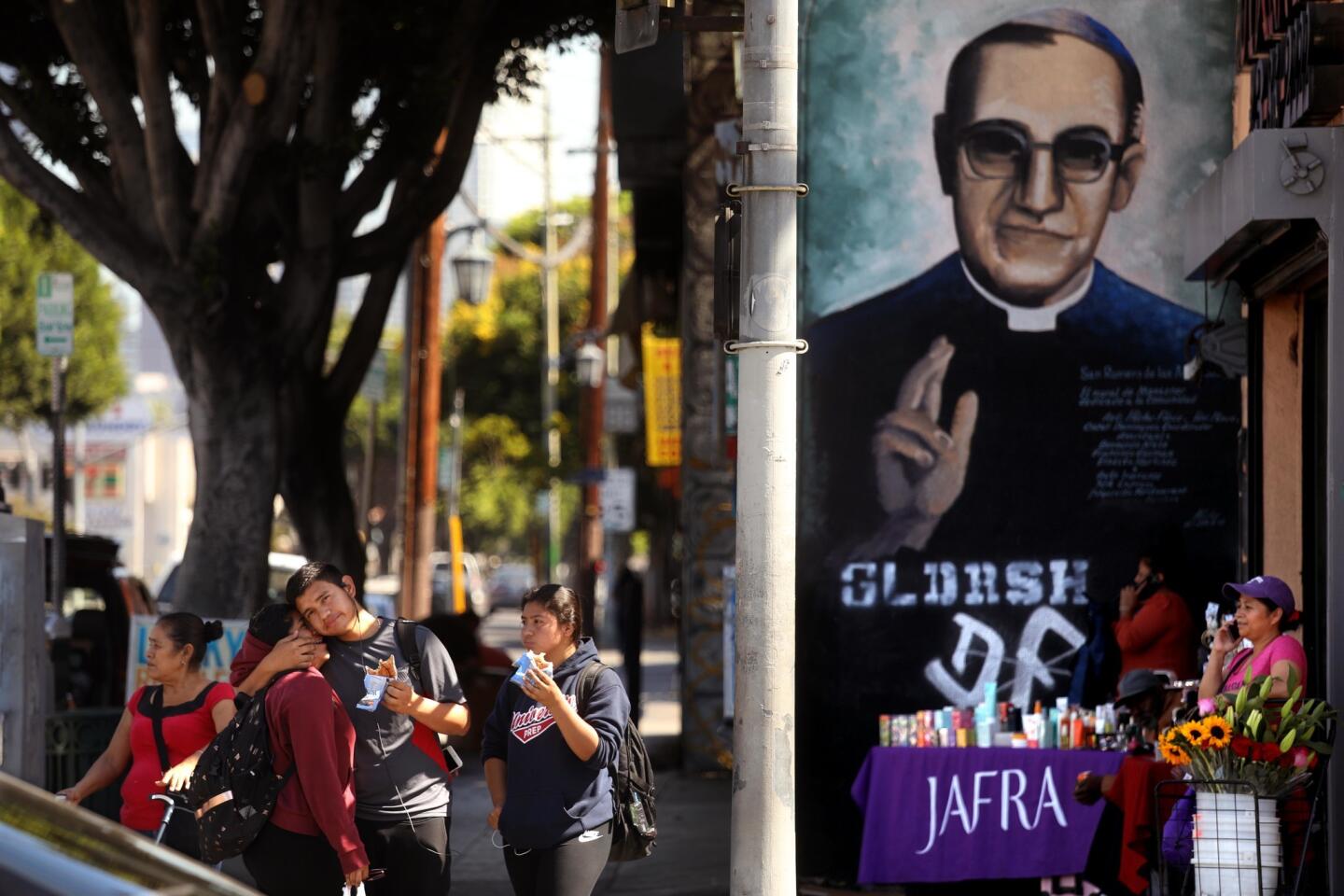

The civil war dragged on for 12 years, the violence so brutal that hundreds of thousands of Salvadorans fled, many streaming into Los Angeles.

The conflict ended in 1992 with the United Nations monitoring a peace accord. But the memories of the atrocities lived on with those who endured the war, and the hope that Romero someday would be properly recognized for standing up to the government never faded.

The morning of Romero’s funeral, snipers opened fire on the masses. They tossed grenades at mourners, sent everyone fleeing in terror. Estrada Posada, who still lives in El Salvador, remembers only fragments. She passed out. She got trampled by the throngs. She was left a sooty, bloodied mess on the ground until someone carried her to safety.

“I’m so nervous,” she said Sunday, her voice cracking. “I want this day to heal me and take my pain away.”

‘He’s always been our lobbyist’

In the multitudes lining St. Peter’s Square, there were pockets of pilgrims from Los Angeles. Many of the Salvadorans displaced by the 12-year civil war, by Romero’s consequential death, ended up settling all over the Southland. Many vowed that when Romero’s canonization came, they would attend, regardless of where it was in the world.

Some tagged along to the Vatican with large groups, for whom every detail of the trip was organized by local churches. Others ventured out on their own.

Sylvia Mejia, 26, and her family from Northridge arrived without tickets to the main event.

There was plenty to keep them busy: a Romero play, a Romero statue unveiling, a Romero photo exhibit; vigils, Masses, concerts, dinners, panel discussions.

But Mejia’s mom, Dorina, prayed for access to the canonization.

Moments before the ceremony, the Mejias had all but lost hope. Then in a coffee shop they met a friendly nun with extra passes.

Sylvia Mejia, a social worker, wouldn’t call herself religious.

But as she stood before Romero’s image, draped prominently over the facade of St. Peter’s Basilica, she felt overwhelmed. This icon had been a constant in her life. Her parents told her and her siblings all about his story. A smaller image of him hung for years inside her bedroom.

“He’s very much a part of my culture, of who I am and who I’ve become,” she said.

Over the years, Romero has transcended time, religion and geography, reaching far beyond the boundaries of El Salvador, a tiny country that proudly calls itself el pulgarcito de America, the flea of America.

His image is often compared to human rights leaders such as Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr. The United Nations pays tribute to him each year on the date of his death, March 24.

When Romero lived, he often spoke of his devotion to his homeland: “If they kill me, I will rise again in the people of El Salvador…. If they manage to carry out their threats, as of now, I offer my blood for the redemption and resurrection of El Salvador.”

At the canonization, pilgrims spoke of him with misty eyes. Many have considered him their saint for decades, long before the Vatican agreed to make it official.

“He’s always been our lobbyist, our lawyer,” said Dolores Copland, 43, of Long Island, N.Y. “Now he has a direct link to God.”

An inspiring figure

With sacred hymns, the papal Mass began. Soon so did the traditional chanting of the Litany of the Saints, the long and lyrical roll call of all the church’s saints.

Ora pro nobis. Pray for us.

Pope Francis, who approved Romero’s sainthood after decades of conservative stalling, was then petitioned three times to recognize as saints Romero, Pope Paul VI and five other lesser-known figures.

When the pope declared them so in the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit, the audience joyfully applauded.

Two Salvadoran women near the center of the square smiled at each other, took a deep breath and locked hands.

Moments later, Pope Francis during his homily returned to Romero, a figure whose sacrifice has personally inspired him.

He advised pilgrims to not go seeking riches, to focus instead on God.

Romero “left the security of the world, even his own safety,” he said.

All to remain close to the poor and to his people.

Twitter: @LATbermudez

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.