Stateless people in Dominican Republic hope to regain citizenship

- Share via

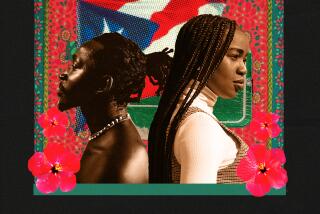

Reporting from Santo Domingo,Dominican Republic — Maribel Campusano Fajardo smiles shyly at the ring on her left hand. “The ring is just a promise, because we can’t get married without the identity card,” the 25-year-old said.

Fajardo’s fiance, Rafael Toussaint, 26, is one of thousands of people born in the Dominican Republic to Haitian parents rendered stateless by legal policies until last month.

In May, the Dominican Congress approved a law that will regularize the status of many people like Toussaint. It ends an eight-month legal standoff that followed a Constitutional Court ruling that canceled the citizenship of those born after 1929 to immigrants without proper documentation.

The ruling made retroactive nationality policies outlined in the 2010 constitution. It affected an estimated 210,000 people, according to the Office of the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees. Most of them were born during an era when citizenship was granted automatically.

The new law will enable those who possess birth certificates — about 24,000 people, according to the government — to regain their citizenship. But those who never had birth certificates will have to prove that they were born in the country and apply for naturalization.

Human rights advocates, who had termed as racist the court ruling and the policies since the 1990s that led to it, are cautiously optimistic about the law. They are concerned about its implementation and for the tens of thousands of people who are expected to seek naturalization.

“A naturalization process is necessarily a discretionary process,” Gonzalo Vargas Llosa, chief of the U.N. refugee mission in Santo Domingo, said. “It’s not a human right to be naturalized; it’s a human right to have a nationality.

“Especially in a country with weak institutions and with a proven history of applying policies in a discriminatory and racist manner.... The possibility of a naturalization process not being fair and just and leaving out a lot of people is very high,” he said.

The legislation follows a national and international outcry. Advocates brought Toussaint’s case and 81 others to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights last year. The commission ordered the Dominican government to protect Toussaint and the others from deportation and to grant them provisional rights.

Dominican authorities framed the previous policies as the nation’s way of coping with difficult immigration issues.

“This is a problem from a long time ago and the Dominican state has the will to change it,” said one lawyer from the Central Electoral Board, which manages birth certificates. He spoke anonymously because he did not have permission to grant interviews.

Toussaint’s parents moved to the Dominican Republic from Haiti decades ago on a temporary visa to work in the sugar industry. For generations, Haitians have crossed the border into the relatively wealthy Dominican Republic. Many worked in sugar fields, and others as maids or construction workers.

The sugar industry spurred the country’s economic growth. Treaties between Haiti and the Dominican Republic granted many people work visas, and many of the children of those immigrants are dealing with the citizenship issue.

“If I open my door to you and say come in to my house, later I can’t say you came on your own,” Toussaint said. “The state opened the door for them.... They weren’t illegal.”

Toussaint said that his father worked in the sugar cane fields until he was injured, and a resulting infection killed him.

Toussaint was born in Santo Domingo, the capital. He speaks Spanish fluently and stumbles over his words in Haitian Creole. He met Fajardo when he was a child and reconnected with her in his 20s. They fell in love and five years later live in a cramped cinder-block home.

He dreams of becoming a police officer. “I wanted to work for my country where I was born, but they made it so I couldn’t,” he said.

For now he sells cellphone accessories on the street, and Fajardo, who is six months pregnant, is the primary breadwinner. She comes from a long line of Dominicans and works for the government in a highway tollbooth.

Their love story shows the distance between the policies and real-life experiences of many Dominicans of Haitian descent. Vargas Llosa said an elite, “unholy alliance between the conservative press, the conservative church, the political sphere and the economic sphere” was to blame for the court ruling.

In January, a poll in the paper Hoy found that more than half of Dominicans surveyed thought children born to immigrants in the country should have citizenship.

“There are a lot of Dominicans who are racist, but many who are not,” Toussaint said.

Fajardo’s family never questioned their relationship.

“I wanted to have a baby, but I thought to myself if I have kids now I will have a whole bunch of problems. I didn’t want it now with all the problems,” Toussaint said. “This year we said finally we decided to try; we trust in God.”

Gaestel is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.