Egypt’s Christians feel safer under Sisi, but bias and injustice persist

- Share via

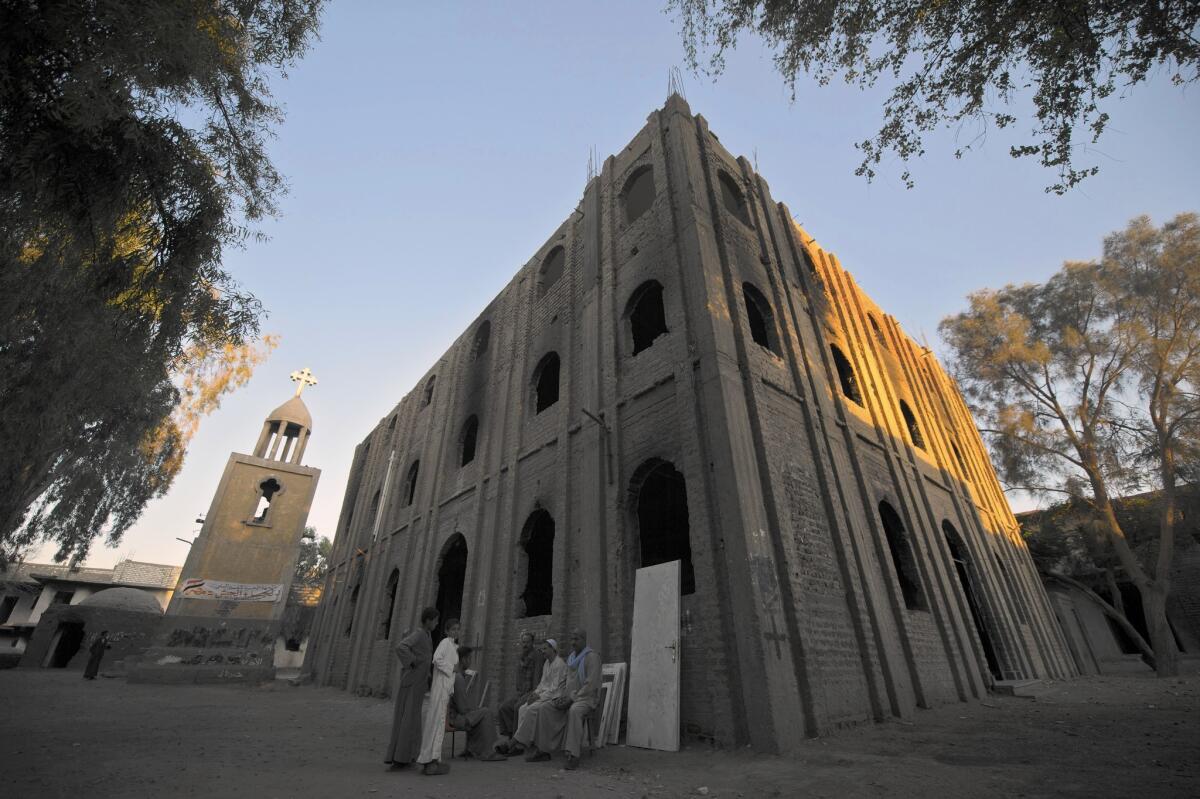

Reporting from DELGA, Egypt — On the outskirts of this village, where the rich green of the Nile Valley abruptly meets the desert, parishioners of the St. George Coptic Catholic church recently built a wall.

It was a simple structure of stone blocks and mortar surrounding a plot of land owned by the church. Father Ayoub Yousef said he hoped to build a dialysis center there so villagers wouldn’t have to travel for treatment.

But last month, local authorities knocked it down, leaving the blocks jumbled in the sand. Yousef said the authorities were responding to complaints from angry villagers, but they showed no legal justification for the demolition.

It was a violation of the law, and of parishioners’ rights, said Yousef, who dresses in long black robes and has a salt-and-pepper beard.

“What we’re asking for is the implementation of the law,” he said. “We don’t want advantages for Christians. We’re not saying Muslims are oppressing us. Just apply the law.”

Yet for Egyptian Christians, that’s often a distant dream.

Discrimination against Christians, who make up less than 10% of Egypt’s population, is nothing new. But attacks against Christians rose after a 2011 uprising overthrew the autocratic government of President Hosni Mubarak, replacing him with a democratically elected Islamist leader, Mohamed Morsi. And the violence may have reached a peak shortly after Morsi was overthrown in 2013.

Many Christians had participated in the uprising against Morsi. So when security forces stormed a protest camp full of Morsi supporters, killing more than 1,000 people, Islamists targeted Christians in retaliation. Dozens of churches and Christian homes throughout Egypt were attacked and burned.

With a high concentration of Christians, Minya, the governorate where Delga is located, was a focal point of the violence.

Supporters of the ousted president seized control of Delga, demanding that Christian families pay protection money. After security forces killed the protesters in Cairo, angry Delga residents burned churches, attacked 20 Christian homes and killed a Christian resident, dragging his body through the streets. It was 73 days before security forces reasserted control of the town.

Some two years later, conditions for Christians in Egypt are markedly better. Many see Abdel Fattah Sisi, the general who led the coup against Morsi and was subsequently elected president, as their protector, sent to deliver them from the rule of Islamists.

The number of attacks and kidnappings for ransom, common in the years after 2011, have dropped. In a historic first that heartened many Christians, Sisi attended a Christmas Eve service in the main Coptic Orthodox cathedral in Cairo in January 2015, and again this year. He ordered the military to rebuild the churches burned in 2013, although progress has been slow.

“God gave us Sisi,” said Medhat Atta Morkos, a 54-year-old pediatrician from Minya who was kidnapped for ransom in 2012. After his release, he said, he lived in fear — not going out at night, and staying away from his rural clinic — but now his life has returned to normal.

“It’s a miracle that Sisi came and saved us from the corruption that happened,” he said. “He saved the country from being destroyed.”

But despite undeniable progress, Egypt’s largest religious minority still endures widespread injustice and discrimination.

Obtaining a permit to build a church, or even conduct renovations on an existing building, requires presidential approval — a daunting bureaucratic hurdle not required of Muslims. Prosecutions and investigations for blasphemy, often targeting Christians, are on the rise. Attacks on religious minorities still go unpunished. Christians are rarely represented in the top ranks of state institutions.

And authorities often deal with sectarian incidents not according to the law, but by imposing traditional reconciliation councils, which usually end with Christians, even if they are the victims, banished from their villages or forced to pay fines.

So although Christians enjoy better security under Sisi, an autocratic leader who brooks no dissent, the underlying reality is still the same, said Ishak Ibrahim, officer for freedom of religion and belief at the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights.

“The state is not addressing the root of the problem,” Ibrahim said. “The number of sectarian incidents may have decreased, but the view of the state has not changed.”

In Delga, where a building belonging to the St. George church still lies in ruins, Christians are feeling uneasy.

The army, which residents say had been deployed in the village constantly since security forces retook it in September 2013, left abruptly last month — on the same day local officials demolished the wall around the church’s plot. Since their departure, Christian residents say they’ve begun to hear threats in the streets.

“Your protectors are gone,” went one. “You’ll see what happens now.”

Noura Shehata Rizk was selling notebooks and pens at the St. George church to raise money for charity work. She said it had been tense since the military vehicles rolled out of the village’s rutted dirt streets.

She doesn’t let her daughter walk alone anymore, and with the memories of the terror they endured in 2013 still fresh, she worries about what could happen now. Accountability for past crimes would help, she said.

“The solution is that anyone who does something is taken and punished, so it keeps others from doing the same,” she said.

Yet impunity for attacks on religious minorities in Egypt is commonplace. Instead of investigating sectarian incidents as crimes, authorities often rely on traditional reconciliation councils, denying victims their rights and access to justice.

In a recent case, a teacher from a Minya village was convicted of contempt of religion for a short video clip he made showing some of his students mocking Islamic State militants. He was sentenced to three years in prison, and he and his family were banished from their village after a reconciliation council.

The four students he filmed were convicted of contempt of religion, and three of them were sentenced last week to five years in prison, the maximum sentence. The fourth was ordered held at a juvenile detention center.

Mina Thabet, program manager for minorities and vulnerable groups at the Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedoms, says Sisi has offered superficial changes to garner the support of Christians, without addressing deeper problems.

“Christians are a marginal group and can be pleased by small things because they have nothing,” he said. “But the solution is not rebuilding some damaged churches. The real solution is allowing Christians to have freedom to practice their religion.”

Yousef says many Christians don’t blame Sisi for their problems, partly because they see authorities at the lower levels, such as police officers, security officials or judges, as responsible for allowing or abetting discrimination.

Plus, “Christians have no alternative,” he said. “What can they do? Fear runs deep in them, right next to the blood in their veins.”

Chick is a special correspondent. Special correspondent Hassan El Naggar contributed to this report.

ALSO

Supreme Court majority blocks Louisiana law restricting abortion providers

How Asian Americans climbed the ranks and changed the political landscape

Knife reportedly found at O.J. Simpson’s former Brentwood estate is being tested by LAPD

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.