- Share via

As the sun set over the Nevada desert, coroners from across the country mingled with business executives, sipping icy margaritas and Tanqueray and tonics by a pool.

The private party, held on the terrace of Las Vegas’ Golden Nugget hotel on a summer night in 2017, was a gift from Cryolife, a biotech company that sells valves sliced from human hearts to be used as medical devices. The festivities reflected the cozy relationship that has grown in recent years between the nation’s coroners and the industry that trades in tissues from human cadavers.

The relationship wasn’t always so warm. Only a decade before, coroners and medical examiners complained they were shut out as the companies helped rewrite the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act. Within three years and with a push from the company’s lobbyists, a version of this new model law had been passed by 46 states.

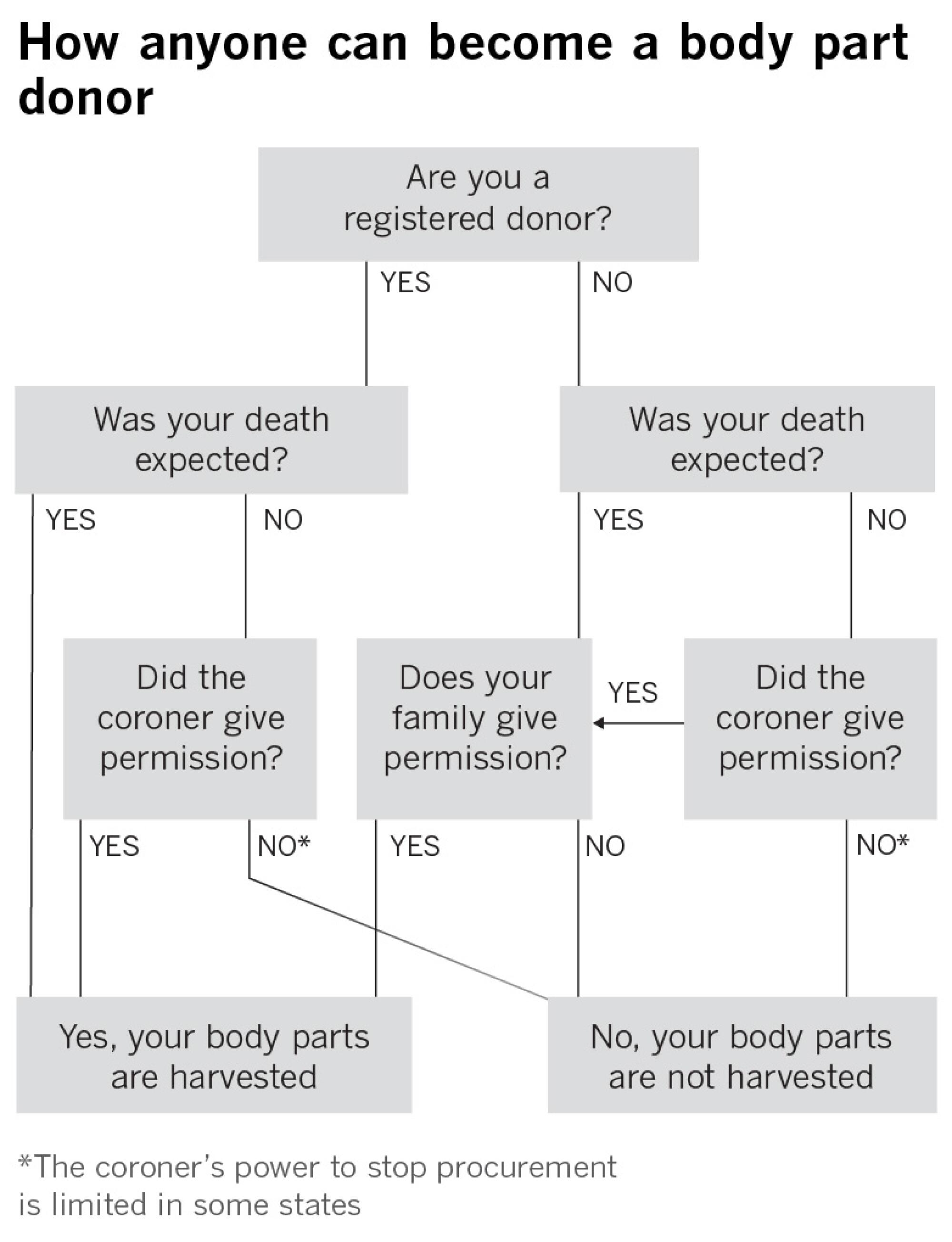

The act makes it much easier for body parts to be harvested quickly — even in cases in which coroners believe it interferes with their ability to determine the cause of death.

Mary Ann Sens, the acting state forensic examiner in North Dakota, had warned state legislators the law “revokes the historic responsibility” of the coroner and gives the procurement companies “equal or greater priority.” Despite the concerns of Sens, North Dakota adopted the proposed law almost verbatim.

As The Times has reported, dozens of death investigations across the country have been complicated or upended when body parts were harvested before an autopsy.

There’s no denying that organs can extend lives, and tissue is sometimes life-enhancing. Corneas can save sight in those going blind. Tendons are used to repair sports injuries. But, in convincing people to become donors, companies rarely mention that a growing part of the multibillion-dollar body parts industry is cosmetic surgery — or that unlike organs, tissues are rarely of immediate need. Distributors employ salespeople whose job it is to persuade surgeons to use body parts rather than materials produced in a lab.

Rewriting the law

Even before the new laws passed, coroners rarely said no when companies asked to procure hearts, kidneys or other vital organs. But coroners often rejected requests to harvest tissues such as skin and bone when they thought it would upend a death investigation.

In July 2003, the companies set out to change state laws across the country to force coroners to cooperate. That month, the trade and lobbying group representing U.S. procurement companies penned a letter to an obscure but powerful organization now known as the Uniform Law Commission.

The group of volunteer lawyers, appointed by state governments, receives suggestions from the public and industry about laws that should be the same in every state. The commission’s meetings are open to the public, although they are not widely advertised. The group specifically invites those it considers “stakeholders” in the proposed legislation to participate.

In their letter, the procurement companies asked the commission to rewrite the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act, which regulated organ and tissue donation in all 50 states. Among the companies’ complaints: Coroners were not allowing donation of body parts in all deaths, even though the previous act had given death investigators immunity from lawsuits related to procurements if they made mistakes.

The companies wrote that coroners should not be able to stop the harvesting of body parts before an autopsy. And they offered to help write the new act.

The letter was written by the Assn. of Organ Procurement Organizations, which represents OneLegacy in Los Angeles and 57 similar companies across the country.

The companies had been empowered by a 1984 federal law to recover hearts and other organs from the dead with the hope of helping desperately ill patients. By 2003, though, some had begun harvesting bone, skin and other tissues needed as raw materials by the biotech industry. Three years later, 80% of the companies were harvesting tissues and sending them in exchange for fees to tissue processors and distributors, many of which are for-profit companies. Today the selling of human tissue is a multibillion-dollar global business.

The procurement companies describe themselves as charities; they must be registered as nonprofits under the law. Yet many spend heavily on promotional campaigns and elaborate lobbying operations, and adopt strategic plans aimed at boosting revenues. At least one pays its top executive more than $1 million a year.

The Uniform Law Commission quickly took up the companies’ proposal.

Only one consumer group attended. Joshua Slocum, executive director of the Funeral Consumers Alliance, told The Times he had tried to add language aimed at reducing the high fees the industry can make. He was concerned about repeated scandals involving the sale of body parts. He was not successful.

The companies’ suggestions heavily influenced the revised act’s text, according to documents from the commission.

A significant change was a new section that said coroners or medical examiners “shall cooperate” with the companies “to maximize the opportunity to recover anatomical gifts for the purpose of transplantation, therapy, research or education.”

The companies said the language was needed to increase the supply of organs. But under the law, “anatomical gifts” also covered skin, bone and other tissues, which the companies argued were needed to help patients through procedures such as back surgeries. The language also expanded the allowed uses of the donated body parts beyond transplantation to research of any kind.

At the suggestion of the industry and advocates of organ transplants, the drafters added a section modeled on a Texas law. It said if medical examiners intended to stop companies from recovering organs or tissues, they must attend the planned procurement procedure in the hospital operating room and make their announcement there.

Dwayne Wolf, deputy chief medical examiner in Harris County, Texas, said in an interview the language makes it much more difficult for medical examiners to stop the procurement of organs. By the time the medical examiner arrives at the operating room, he said, the transplant surgeons are in place and the donor’s family is expecting the procedure.

“No one is going to the O.R. and interfere in that process,” Wolf said. “We really can’t stand in the way.”

In 2006 the law commission began lobbying to get the model act passed in every state. In a note to state legislators, the commission said the legislation had been written after “extensive discussions” with the National Assn. of Medical Examiners, one of the nation’s most influential groups of death investigators.

That wasn’t true.

“It is particularly disturbing to our organization that a significant portion of the drafting process … occurred without any consultation with the medical examiner community,” the association wrote in a Feb. 28, 2007, letter to every state legislature.

The medical examiners’ group wrote that the proposed law contradicted the legal mandate of medical examiners to collect and preserve evidence and determine the cause of death. And it questioned why the procurement of tissues should be given the same priority as organ donation.

Carlyle “Connie” Ring, chair of the drafting committee, told The Times that the commission had repeatedly tried to get the nation’s death investigators to participate.

“You’re correct that medical examiners did not attend the drafting sessions in any large numbers,” Ring said. “We didn’t have communication as much with them as with other interests.”

At hearings across the country, local medical examiners warned of the law’s consequences.

“Once evidence is destroyed, it is too late, it cannot be recaptured,” Marie-Lydie Pierre-Louis, chief medical examiner of the District of Columbia, testified in June 2007.

Pierre-Louis warned the loss of body parts before the autopsy would interfere with court proceedings and result in officials failing to recognize threats to public health.

Jeffrey Taylor, then the U.S. attorney for the District of Columbia, joined Pierre-Louis in opposing the legislation. His office wrote in a letter to lawmakers that the removal of organs or tissue could compromise prosecutions of homicides, a problem that had plagued the district for nearly two decades. In homicide investigations, the letter said, “it may be as important to establish what did not kill the decedent as what did.”

In some states, including California, the protests led to amendments that made it harder for companies to obtain tissues than organs. But most states passed the law much as it was proposed, persuaded by the companies’ lobbyists, who said people on transplant waiting lists would die without it.

In the years since the laws passed, though, they have worked more to benefit the biotech companies selling products derived from human cadavers than to increase the supply of organs.

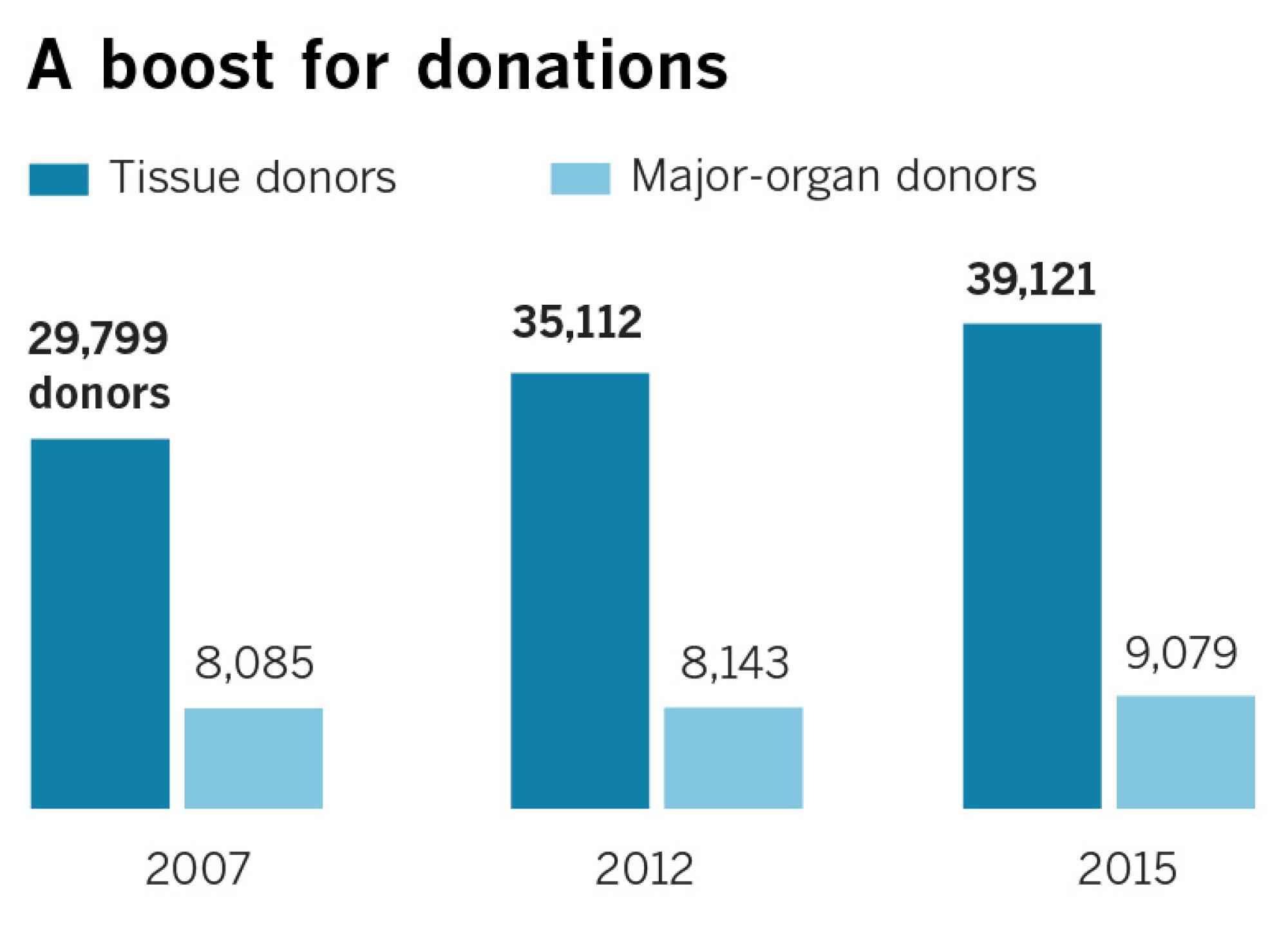

Robert Hale, supervisor of tissue operations at Donor Network West in Northern California, called the growth in donated body parts “astounding,” in a 2016 presentation. From 2011 to 2015, the number of donors of bone, skin and other tissue recovered by the company increased 88%, from 1,214 to 2,280, he said.

In comparison, the company recovered organs from 300 donors in 2015, according to its annual statement. That was one more donor than in 2011.

Hale said in his presentation that each donor body was supplying raw materials for more than 100 tissue implants — a number that grew each year as the industry developed new products.

Some of the hottest new products were on display at the world’s largest annual plastic surgery meeting in Orlando, Fla., in 2017. Doctors entering the conference hall were greeted by 15-foot banners promoting processed skin from cadavers. Surgeons said they used the skin for myriad cosmetic procedures, including penile augmentations and fixing breast implants that had fallen out of place.

Among the most talked about innovations was Renuva, a syringe filled with human fat, used to plump lips, cheeks and buttocks. A consultant hired by its manufacturer, MTF Biologics of New Jersey, told a crowd of surgeons that one of the product’s few hurdles was that “it takes a lot to make a little.”

The companies now harvest so much tissue from Americans that they are increasingly exporting it overseas.

Canada has such ready access to Americans’ body parts that tissue banks aren’t pressured to find donors in that country, according to a 2017 study. The country’s imports of deceased Americans’ skin have grown especially fast. The skin imports leaped by 25% in 2012, an analysis found, with similar double-digit growth projected through 2017.

Elling Eidbo, chief executive of the Assn. of Organ Procurement Organizations, said he did not know how much tissue was used for cosmetic fixes. He said tissues are used for important medical treatments. For example, he said, corneas can prevent blindness and skin can help treat patients with serious burns.

Such uses are emphasized in the industry’s campaigns that urge Americans to sign up to “Donate Life.” The campaigns avoid discussion of cosmetic surgery.

Members of the Uniform Law Commission told The Times they are pleased with the results of the revised act.

“The law has been working in terms of what our goal was, which was to increase the supply of organs,” said Sheldon F. Kurtz, a former commission member and University of Iowa law professor who helped draft the model law.

Gifts of cocktails and catered feasts

Since the laws passed, the companies’ lobbyists have worked hard to build alliances with death investigators.

“Thank you Kim and friends at Upstate NY Transplant Services for the most educational and wonderful weekend,” Scott Schmidt, president of the New York State Assn. of County Coroners and Medical Examiners, wrote in a 2009 newsletter. The group’s conference at Barton Hill Hotel & Spa had included meals, wine and a hospitality suite.

Schmidt wrote that four procurement companies had “never” wavered in their support for the group’s events and that fees to attend would “easily double” without their money. In 2018, the companies continued the payments.

“They do it to develop a relationship with us,” Schmidt, chief coroner of Orleans County, told The Times. He said he previously opposed procurement of tissues before the autopsy but “had my mind changed.” That wasn’t because the companies “had their checkbook there to pick up a happy hour,” he said, but because “they are educating us that donation can be done without jeopardizing our cases.”

Schmidt said under New York law he can’t stop the companies from taking body parts, so he’s learned to work with them. “There’s no good argument against donation,” he said.

The California State Coroners’ Assn. was soliciting cash last fall from procurement companies and other businesses to help pay for its annual symposium, which included a cocktail reception, luncheon and a night out at a Santa Rosa restaurant. The group asked for more money to pay for meeting rooms at the Flamingo Conference Resort & Spa and raffle prizes of weekend getaway trips.

“Checks should be made payable to CSCA,” Gary Tindel, the group’s executive secretary and Yuba County’s former sheriff-coroner, wrote in a note soliciting the payments. Tindel refused to disclose to The Times which companies ultimately helped pay for the five-day event.

Jonathan Jacobs, director of John Jay College’s Institute for Criminal Justice Ethics, said medical examiners and coroners are public officials with crucial responsibilities who should not be allowed to accept gifts or industry payments.

Gifts or preferential treatment raise “ethical scrutiny,” Jacobs said. “Why invite suspicions of these kinds?”

Some companies have also added death investigators to their boards and paid them director fees.

OneLegacy began paying more than $2,000 a month to Lakshmanan Sathyavagiswaran to sit on its board less than two years after he retired as L.A. County’s chief medical examiner-coroner in 2013. During his 20-year tenure of overseeing the morgue, Sathyavagiswaran put in place a “zero denial policy” in which the goal was to greenlight OneLegacy’s requests to harvest organs, he explained on his resume. The policy was designed “to insure a balance between protecting the integrity” of the death investigation, he wrote, “while increasing the supply of organs.”

Sathyavagiswaran resigned from the OneLegacy board in 2016 when the county asked him to temporarily direct its morgue again. He no longer works for the county and didn’t respond to requests for comment.

In St. Louis, the city’s chief medical examiner, Michael Graham, sat on the board of Mid-America Transplant for 27 years, according to his resume. Company financial reports show Mid-America paid him $500 to $2,000 a year since at least 2004.

Graham said his board seat had helped him work with the company. “We don’t give them carte blanche,” he said. In a later interview, Graham said he was no longer on the board.

In news releases, on websites and in interviews with the media, the companies have criticized coroners who blocked their requests for body parts.

A website aimed at passing a 2016 Pennsylvania bill that would force coroners to cooperate with the companies said the state’s forensic investigators had “a deadly pattern” of blocking donations of organs. The website specifically called out Westmoreland County Coroner Kenneth Bacha, saying he had denied more of the companies’ requests for procurement than all coroners in the states of Florida, New Jersey and Missouri combined. The website said hundreds of patients were needlessly dying. “DELAY = DEATH,” it said.

Bacha told The Times the statistics were “absolutely false.” He said he supported organ donation but had lost trust in a company after he allowed procurement in the case of a possible drug overdose. The Center for Organ Recovery & Education in Pittsburgh promised to save a blood sample so he could test drug levels, he said, but never delivered, leaving the cause of death uncertain. Instead he used evidence at the scene to decide it was a heroin overdose, he said.

T.J. Roser, the company’s coroner liaison, said he wasn’t aware of the case.

Some coroners say they are hesitant to speak out because they fear the companies will publicly criticize them. At the same time, the companies frequently gave awards and public praise to the death investigators who cleared the way for their recovery teams, creating a one-sided chorus of satisfaction with the rising number of procurements inside the morgues.

“If donation is something the family gives permission to do, and precludes me from ever finding out why their loved one died, I’m OK with that,” Mary Case, a Missouri medical examiner, said after receiving an industry award in 2016.

Flawed paper gave industry cover

A key target of the industry lobbyists has been the National Assn. of Medical Examiners — the group that said it had been shut out from revisions of the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act.

At the group’s 2017 conference at the DoubleTree Resort in Paradise Valley, Ariz., Cryolife helped pay for golf rounds at the “Cadaver Open,” while MTF Biologics covered the cost of wine at a reception attended by hundreds.

MTF Biologics, the maker of the cosmetic filler Renuva and one of the largest human tissue processing companies in the world, said it gave the money in support of the medical examiners’ “overall mission.” Cryolife didn’t respond to questions about its gifts.

The procurement companies have become so influential at the medical examiners’ association that their executives now sit on the group’s board of directors. The association’s current chairman is Kim Collins, medical director of tissue recovery services at We Are Sharing Hope SC, a large procurement company in South Carolina.

Collins said she did not believe the companies’ financial contributions could sway medical examiners but agreed there was a “perception” of a conflict of interest. She said she planned to have the board discuss the appropriateness of accepting the industry’s money.

That board sets the association’s policies. And in 2014 it signed off on a paper written by seven of its members that concluded that organs or tissues could be harvested “in virtually all” deaths with no consequences to autopsy findings.

Its authors wrote they came to that conclusion after failing to find a single case in which a death investigation was “negatively impacted by donation.” The authors cite as evidence a 1994 newsletter from a committee of the American Bar Assn. They said their own review found no cases since then.

Times reporters, however, found at least six cases through simple searches of media reports, court opinions and scientific articles that would have been available before the paper was published in 2014.

In one case, an Indiana prosecutor shocked a Wayne County court in 2009, saying he was dropping charges against James McFarland, who was being tried on a charge of murdering his 19-year-old girlfriend. The jury had already been selected when the prosecutor announced that the pathologist who performed the autopsy of Erin Stanley had suddenly revealed he was no longer sure McFarland had strangled her.

The pathologist explained, according to news reports, how a procurement team had washed Stanley’s body before his autopsy and then harvested skin and bones. In the process, the team had mutilated her neck with syringes in attempts to draw blood samples. He explained he was no longer sure whether the blood he found in the deceased woman’s neck was caused by being strangled or left by the syringe needle.

In another case, in Ohio, the parents of Kevin Piskura had sued Taser International after he died days after being hit in the chest with the company’s stun gun during a fight with police.

Lawyers for Taser argued Piskura died of “alcohol poisoning,” and not from the company’s stun gun, after a chest wound described by his doctor and parents was not found in the autopsy, according to a 2013 court decision. His physician and parents said they believed the wound from the Taser dart, which had been visible on his chest in the hospital, disappeared when his organs were procured.

The company told The Times the case was dismissed.

Times reporters also found more than two dozen other cases in two Southern California morgues where procurement appeared to hamper death investigations.

Published in the association’s scientific journal, the paper has been cited by legislators enacting laws and coroners responding to public concerns. Many county morgues include links to it on their websites. Company representatives, in interviews with The Times, have called it “scientific” proof there was no harm from their increasing activities in county morgues.

What is rarely if ever mentioned is that two of the paper’s seven authors work as top executives at procurement companies and two others are medical examiners who serve on a company’s advisory committee.

One of the authors, Daniel Schultz, made $324,000 in 2016 as director of human tissue operations at Lifelink Foundation in Florida, according to its tax filings. The company received almost $30 million for bone, skin, heart valves and other tissues that year.

Last year Schultz and Lifelink were sued by a family after the company took the heart of Duane Mulville, a former minor league catcher who died unexpectedly at age 48 at his Georgia home. Mulville had signed up as a donor in another state. His wife, Beverly Mulville, said she asked the company not to take her husband’s heart. She said she intended to have a private autopsy determine whether he died of an undiagnosed heart condition that could have been passed to her six children. The autopsy could not determine why he died.

A Lifelink spokeswoman said the company doesn’t comment on pending litigation. She said Schultz was not available to comment.

The paper’s other corporate author was Samantha Wetzler, assistant medical director at LifeNet Health, in Virginia Beach, Va. The company received $297 million for bone, skin and other tissues in 2016, federal tax filings show.

Douglas Wilson, executive vice-president at LifeNet Health, said the company had not encouraged Wetzler to write the paper or given her extra compensation for it.

In an email to The Times, Wetzler said she would welcome evidence of problems caused by body part procurement. After The Times sent her details of cases in which procurement interfered with the death investigation, she did not respond.

The paper states critics are wrong to say human tissues are processed into commodities that are “stocked” on inventory shelves and left to sit for years. Instead, the paper describes the tissues as being of “immediate need” by patients. Yet The Times found processed bone and skin in brightly colored packages, stamped with expiration dates years in the future.

Collins, the association’s chairman, said the paper was written to educate medical examiners and not to benefit the procurement industry.

“All the authors are pro-donation,” she said. “But I can’t see how any of them wouldn’t put their patient — the decedent — first.”

Collins said she didn’t know why the authors had not found cases such as the failed murder prosecution in Indiana or the Taser wound that seemed to disappear. “Those are disturbing,” she said.

The authors also misstated the conclusion of the 1994 newsletter they cited. Teresa Shafer, who was an executive at LifeGift, a Texas procurement company when she co-wrote the newsletter, pointed out in an interview that the work had involved determining whether the recovery of organs had affected death investigations. It did not deal with tissue procurement, she said. “Tissue donation is more invasive,” she said.

Shafer, now an industry consultant, said she doesn’t believe tissues should have the same priority as organs in the law. “If that organ is not transplanted, someone is going to die,” she said. “Bone is not lifesaving.”

In addition to their jobs as procurement executives, Schultz, Wetzler and Collins also perform autopsies for county morgues as trained pathologists. Many governments are eager for such outside help because of a nationwide shortage of forensic pathologists.

The dual roles, however, raise questions when their corporate employers ask to harvest body parts before an autopsy. If they deny a procurement to safeguard an investigation, it hurts their corporate employer’s bottom line. If they allow the harvesting of body parts it could keep them from determining the cause of death.

Stefan Timmermans, a UCLA professor of sociology who has studied the history of the procurement companies’ work inside morgues, said the dual jobs raised questions about conflicts of interest. “You need to be very strong ethically to separate those two roles.”

When Collins has performed government autopsies, she has at times been asked by her Sharing Hope colleagues to approve procurements. “I’ll deny some cases,” Collins said. She said as medical director at Sharing Hope she isn’t involved in executive decisions and doesn’t see her two jobs conflicting.

Not long after the paper was published in 2014, Wetzler gave a presentation to coroners in Colorado and Wyoming, citing its claim that procurement had never interfered with a death investigation.

“Yes, tons of people have anecdotal stories, but for whatever reason they’ve never been documented and published, so they can’t really be reviewed,” she said, according to the webcast.

She told the coroners — many of whom are elected — it wasn’t in their political interest to deny donation. “There is no politician who can advance their career by saying they are not on board with organ and tissue donation.”

Wetzler said that when she performed autopsies as a medical examiner she told the procurement companies, “Go ahead and take what you need. I just need photos before you start.”

Arkuie Williams, administrative deputy in Virginia’s chief medical examiner’s office, told The Times the state has since changed its policy so that procurement company employees who serve as part-time medical examiners can no longer authorize the harvesting of organs or tissues.

The paper, meanwhile, continues to be brought up when the industry’s position is challenged.

“There’s a position favored by the National Assn. of Medical Examiners that zero denial should be a goal for tissue donation,” Frank Miller, chief deputy coroner in Lorain County, Ohio, testified in a 2017 deposition explaining why he let a company take the heart of a teen when it was unknown why she had died. “And so in most or all cases I allow it.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.