Column: The new child tax credit will remake American family life for the better

- Share via

Starting Thursday, the money will begin to flow in one of the most important government initiatives ever aimed at transforming the economics of family life in America.

It’s the child tax credit, which will deliver $3,000 per child ($3,600 for children 5 and under) to the vast majority of families over the next year. Half the amount will be provided in monthly payments over the next six months, and the rest after families file their tax returns for 2021.

However it’s disbursed, the money is expected to be transformative for millions of families. Building on a program last enacted in 2017 in a more limited form, the child tax credit is part of the American Rescue Plan signed by President Biden in March.

The most important job in democracy is the job of child-rearing.

— Michael Tubbs, former mayor of Stockton, Cal.

The entire plan, which includes enhanced food stamp benefits and other safety-net features, is projected to help cut the child poverty rate in the U.S. nearly in half, to 7.5% from 13.6%, according to an analysis by Columbia University. But the child tax credit is its biggest component.

“It’s a massive expansion of a credit that’s been around for a long time but only helped some families,” says Natalie Foster, co-chair of the Economic Security Project, which presses for programs to place more economic power in the hands of ordinary Americans. “This will help virtually all families.”

Anti-poverty groups like Foster’s are organizing to make the child tax credit a permanent part of the U.S. economy, rather than a one-year pilot.

That’s important because safety-net programs for children have both immediate and long-term benefits.

The first payments from the expanded federal child tax credit are being deposited in families’ bank accounts this week. Here’s what to expect.

“Giving cash to families with children will both reduce child poverty today and increase mobility out of poverty tomorrow,” Christopher Pulliam and Richard V. Reeves of the Brookings Institution wrote recently. Children in families that participated in programs offering unconditional cash transfers have shown improved educational attainment and emotional and behavioral health.

Those with higher exposure to the government’s earned income tax credit for low-income households “are more likely to graduate high school and college, be employed as young adults, and have higher earnings,” Pulliam and Reeves reported. These are all factors in improving their mobility out of poverty and the low-income segment.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

The credit actually is even more significant than that. It’s the closest the federal government has ever come to funding a nationwide experiment in the concept known as universal basic income.

As the term implies, UBI means providing individuals and households with an income floor of unconditional cash. A check would go to everyone, whether they’re employed or not.

No strings attached. No means test. No bureaucrats examining your personal lifestyle or looking for hidden income. No politicians demanding that you seek out even a menial job or leave the children in the hands of caretakers before getting the money.

Nine such programs have been launched in localities across the country, with 20 more in the pipeline, including in Los Angeles, Oakland, San Francisco, San Diego and Long Beach.

Among the highest-profile UBI pilot programs was a two-year program launched in Stockton in February 2019 under then-Mayor Michael Tubbs. The program gave 125 randomly selected residents $500 a month for 24 months.

The largest program underway is the Compton Pledge, which is providing 800 residents of that city up to $600 a month. The $9.2-million privately funded program launched by former Compton Mayor Aja Brown began in December and will run for two years.

If there’s one thing that many anti-poverty activists and free-market advocates agree on, it’s that our existing social safety net isn’t capable of dealing with the challenges presented by the evolution of the economy and of the very definition of work.

“The idea of recurring cash is increasingly popular,” says Nika Soon-Shiong, executive director of the Fund for Guaranteed Income, which is helping to provide funding and helped launch the Compton Pledge. Soon-Shiong, a co-director of the Compton Pledge, is the daughter of Dr. Patrick Soon-Shiong, who owns the Los Angeles Times.

With child tax credit payments showing up in recipients’ bank accounts and mailboxes beginning Thursday, it’s timely to examine how the credit and UBI programs differ from what is normally thought of as welfare, and how they represent a vast improvement over more traditional features of the social safety net.

To begin with, they’re inclusive. Even more important, they’re almost entirely unconditional.

(By that standard, the child tax credit falls a bit short of the UBI ideal. Not only does eligibility depend on households having children younger than 18 in residence, it does carry some income limits: Married couples earning up to $150,000 and singles earning up to $75,000 can receive the full credit. Households exceeding those limits can receive smaller amounts, up to couples earning $440,000 and singles earning $240,000, for whom the phase-out is complete.)

Most other safety-net programs either establish stringent income standards or dictate where the money is to be spent — for example, for food, or heating bills or rent. By contrast, UBI programs trust recipients to make rational choices with unrestricted cash.

That principle isn’t new: It dates back at least to Harry Hopkins, who as Franklin D. Roosevelt’s assistance czar viewed the purpose of those programs as putting food on the table without subjecting enrollees to demeaning inquiries into their social habits and economic situations by social workers.

The coronavirus crisis may mean that the time has come for universal basic income’s closeup.

To this day, however, social programs are infected by critics’ suspicions that their beneficiaries are somehow morally undeserving or incapable of making responsible decisions. That’s the gist of the complaint about the child tax credit aired by Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.), who disparaged the plan in February because it didn’t incorporate requirements that recipients have a job, be married or seek treatment for substance abuse.

“If pulling families out of poverty were as simple as handing moms and dads a check, we would have solved poverty a long time ago,” Rubio wrote. “For decades, there was a bipartisan consensus that work, marriage, and community were critical pieces of poverty reduction.”

This is the same Marco Rubio, by the way, who basked in praise for shoehorning an expanded child credit into the Republican tax cut bill in late 2017. That credit required recipients to be employed, a rule that has been eliminated in the new program.

Despite Rubio’s assertion, the truth is that “handing moms and dads a check” has been shown to be more effective at lifting people out of poverty than saddling recipients with intrusive conditions. As Foster told me years ago, “poor people and the middle class know best how to spend their money. They just don’t have it.”

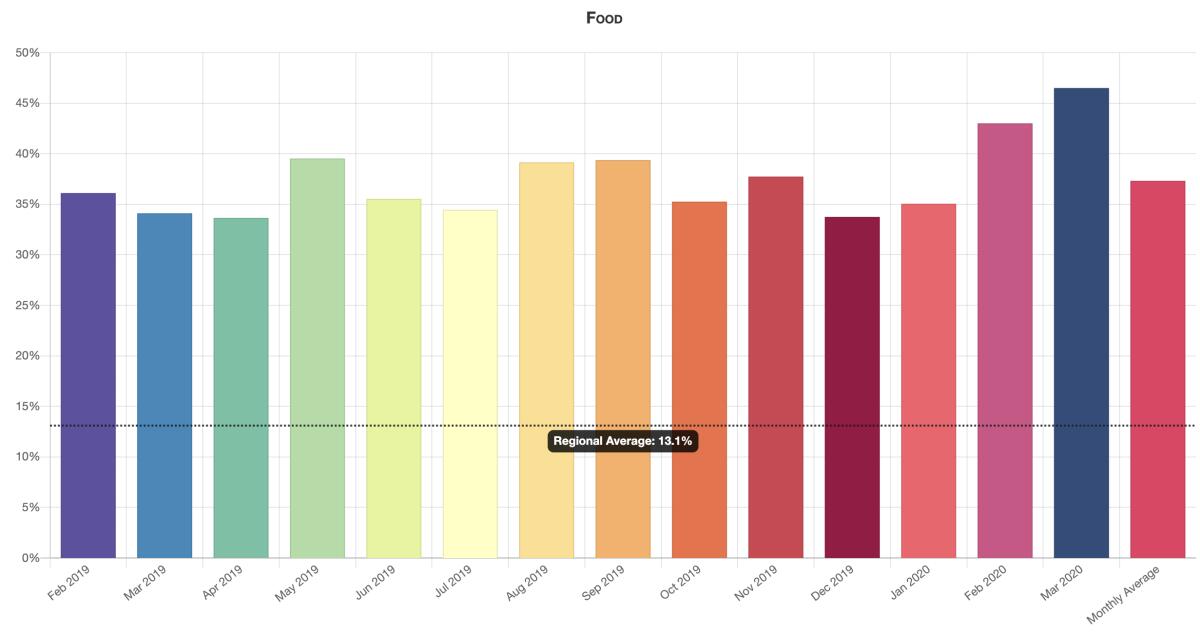

An analysis of the first year of the Stockton program found that the money was spent on crucial needs such as food, shelter and utilities — and recipients stepped up their food spending early last year in anticipation of pandemic lockdowns.

The analysis also found that many participants used the opportunity afforded by the cash to improve their work situations — 28% of recipients had full-time employment at the outset of the program; a year later, 40% did. By comparison, full-time employment in the control group rose from 32% at the start to 37% after a year.

In other words, recipients were able to move into full-time work at about twice the rate of the control group.

“Individuals were able to leverage the $500 in ways that enabled them to show up and fill out a job application — if you’re working part time and taking care of a child, there’s not a lot of time in your day,” Stacia Martin-West, an expert in social work at the University of Tennessee, told me. “Financial scarcity creates time scarcity.”

That conforms to the experience of other unconditional programs such as Alaska’s Permanent Fund Dividend, which has distributed money from the state’s oil boom since 1982.

“We’re seeing that the money is paying for rent, paying for food,” Nika Soon-Shiong says, though a formal analysis of the Compton Pledge hasn’t been completed. “All this goes further to debunk the welfare stereotype that people are going to spend the money on drugs and alcohol. They’re spending the money on investing in their families and investing in their communities.”

That’s the example set by Christine, 44, a Compton Pledge participant with a 4-year-old daughter who is working to establish a nonprofit to help homeless and low-income residents with meals, clothing, housing and transportation. (She asked that her last name not be published to protect her privacy.)

Compton Pledge funding has supported Christine during the months in which she has had to stay home from her part-time job as a Metro bus driver to care for her daughter, whose asthma presents her with an added risk from potential COVID-19 infection.

Recipients of Stockton’s $500 guaranteed monthly income benefited in myriad ways.

Christine’s experience parallels that of other households existing on the razor’s edge of low income, where any unexpected expense can overturn a family’s lifestyle. That’s especially true due to inflation, which is rising as the nation emerges from the pandemic.

“All the prices have gone up,” she told me, mentioning a couch she needed for her apartment that nearly doubled in price before she could buy it and a used car on which the price tag has risen to $6,700 from $4,000 while she’s been in the market. “I don’t know how people expect anyone to live with everything so high,” she says.

Parents face unique pressures, which is why the child tax credit could be a godsend for millions of families.

“The most important job in democracy is the job of child-rearing,” says Tubbs, who is currently co-chair of Mayors for a Guaranteed Income, a network of municipal leaders advocating for UBI. (The other co-chairs are Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti and Melvin Carter, mayor of St. Paul, Minn.)

“It’s exciting because of what it means for the next generation of children to grow up not in poverty and with parents who have the resources to provide for them,” Tubbs says. “The basic income in Stockton was spent on children — on child care, on school supplies, on food.”

The child tax credit, he says, “is going to allow parents the time to parent, to not be anxious and stressed but to be present as parents. We know that poverty is an adverse childhood experience. This should have been done 100 years ago. But I’m glad we’ve arrived at that point today.”

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.