Column: Closing schools in the pandemic was bad. Keeping them all open would have been worse

- Share via

If there’s one aspect of pandemic policy that seems to have elicited agreement across the political spectrum, it’s that closing schools and keeping them closed into 2021 was a blunder.

The consequences of extended school closures were brought home, vividly, with the release late last month of reading and math scores for fourth- and eighth-graders, documenting a sharp slide in proficiency since the pre-pandemic year of 2019.

Even before then, opinion was coalescing around the idea that the schools should have remained open. “What a mistake that was,” New York Gov. Kathy Hochul, a Democrat, said in August, referring to the state’s decision to switch pupils to remote learning in March 2020.

Younger age groups were deeply involved in the spread of the infection.

— Mattia Manica et al

For many educators, politicians and policy wonks, the statistics ended the debate. Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, a champion of letting COVID-19 rip through his population with little interference, crowed that the results “prove that we made the right decision” to keep schools open.

Yet there’s much more to consider. The question that never gets raised, much less answered, when the conversation turns to how bad the school closures were, is: “Compared to what?”

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

“What would have happened had schools remained open without any mitigation measures?” New York neurologist and psychiatrist Jonathan Howard asked recently.

“One obvious answer,” Howard observes, “is that nearly all children would have gotten COVID, as would everyone they live with, and most school employees.”

The number of deaths among children younger than 18, which the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention pegs at 1,853, “would have been higher had 60-70 million unvaccinated children contracted the virus over several months’ time in 2020. It’s reasonable to assume that several thousand children would have died.”

The debate over school closings, like so much pandemic-related discussion, is infected with myths, misinformation and ignorance. It’s proper to note, first, that when the initial school-closing decisions were made early in 2020 no one knew much of anything about the coronavirus.

Florida’s study advising young men to avoid the COVID vaccines is hopelessly unscientific.

There was little consensus about how it spread, at what stage of sickness it was most contagious, or who was most susceptible. The best mitigation measures were uncertain, but it made sense to limit concentrations of vulnerable populations in small spaces, i.e., classrooms.

Pressure to reopen schools started almost immediately, based on assumptions that the virus was no greater health threat than the flu and that children were immune.

Today’s received wisdom is that classrooms “were not locations of significant COVID spread,” as Brown University health economist Emily Oster, a critic of school closings, told me last month.

But that’s not true, according to recent research. Studies from Italy and France establish that schools were significant sources of COVID spread. “Younger age groups were deeply involved in the spread of the infection,” the Italian scientists found. Among other factors, infected pupils transmitted the virus to a larger number of individuals than infected persons in the general population, possibly because they interacted with more people than the average.

Those findings might explain what happened when Florida opened its schools in August 2021 and banned remote teaching: Child COVID deaths in the state more than doubled by the first week of September. One month into the reopenings, districts across the state were being forced to shut down schools and impose quarantines affecting thousands of pupils.

Opponents of anti-pandemic measures such as masks and vaccines tend to dismiss the toll on children as too minimal to warrant concern. It takes a special kind of ignorance and heartlessness to overlook the child death toll to the point of opposing vaccinating children against COVID, as does Florida’s benighted surgeon general, Joseph Ladapo.

Who paid for the college education for GOP critics of Biden’s student loan relief? The taxpayers, that’s who.

Howard points out that death is not the only pediatric COVID outcome to care about. More than 1 in 5 children hospitalized with acute COVID infections suffered lasting neurological conditions, according to a 2021 study. Thousands may have suffered severe neurological conditions, even including stroke. The COVID pandemic appears to be responsible for a spike in multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children, or MIS-C, a life-threatening condition in which the heart, lungs, kidneys, brain, skin, eyes or gastrointestinal organs become inflamed. The CDC reported nearly 9,100 cases between mid-May 2021 and Oct. 31, 2022, including 74 deaths. Nearly half the cases were in children ages 5 to 11.

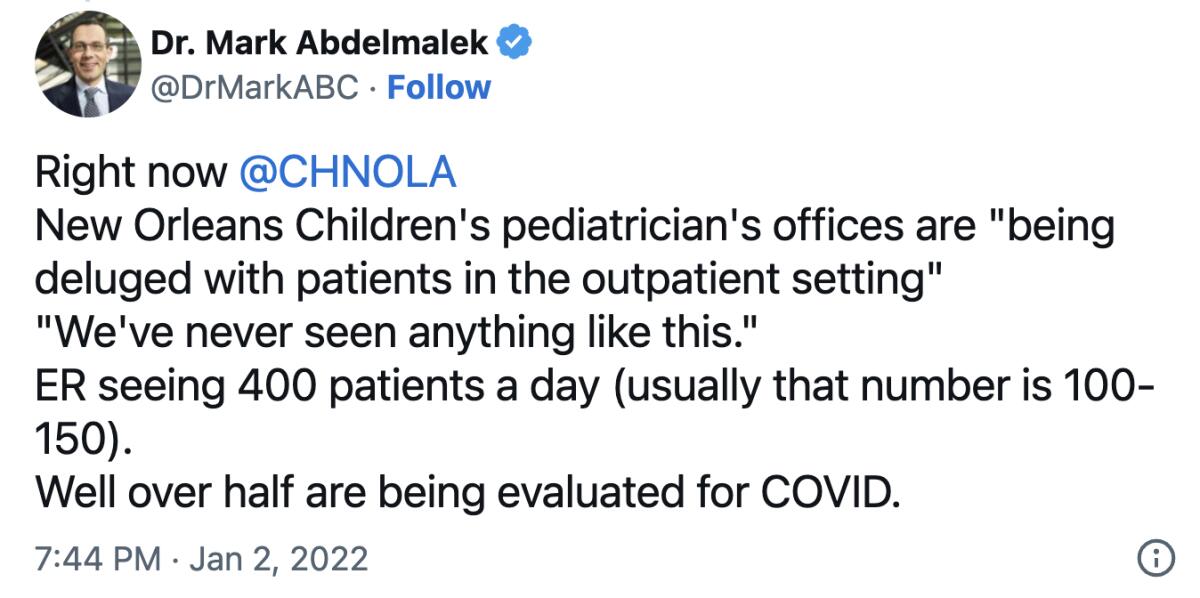

Hospitals across the Southeast, where anti-pandemic school policies were typically lax, were overrun with patients during the Delta and Omicron surges in 2021 and early this year.

The outbreaks were fueled by low rates of child vaccination against the virus, the product of anti-vaccination propaganda that was sometimes distributed by officials in states such as Florida. By early January, CDC statistics show, an average of 914 children were being hospitalized every day with COVID, up from about 90 per day in mid-October.

Another rarely discussed aspect of how the pandemic has affected children is that more than 214,000 American children have lost one or both parents to COVID during the pandemic, and tens of thousands more have lost caregivers such as grandparents. This may be related less to school closings, but is germane to the systematic abandonment of anti-COVID measures nationwide.

This is a hidden crisis, child-care experts say. “Children losing caregivers to COVID-19 need care and safe, stable, and nurturing families with economic support, quality child care, and evidence-based parenting support programs,” a CDC study noted, adding that the loss of caregivers “increases risks of short-term trauma and lifelong adverse consequences” for the bereft children. But scant resources exist.

Put it all together and it becomes clear that the discussion of the pandemic’s effect on children shouldn’t start and end with whether schools should have been opened or kept closed. DeSantis may crow about his state’s having kept its schools open, but Florida’s record on the educational impact was distinctly mediocre. In any event, his opposition to anti-pandemic measures has placed Florida 12th-worst in overall COVID death rates. (California, which favored stringent measures, has the 12th-best rate.)

It’s possible that keeping schools closed was a big mistake. But we don’t know. What’s worse, we’re not asking the right questions. “Those who make this claim should honestly grapple with what would have happened had nothing been done,” Howard wrote, “rather than indulge an absurd, revisionist fantasy that everything would have been fine and dandy.”

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.