After 18 months reporting on the homeless crisis, this is what I learned

- Share via

Stepping up to strangers and asking them to share their stories often gives me pause, and approaching those who are homeless, especially those living in tents pitched on sidewalks, seems presumptuous. But it is also a privilege: to give a voice to the voiceless and insight into an overlooked, even shunned corner of society.

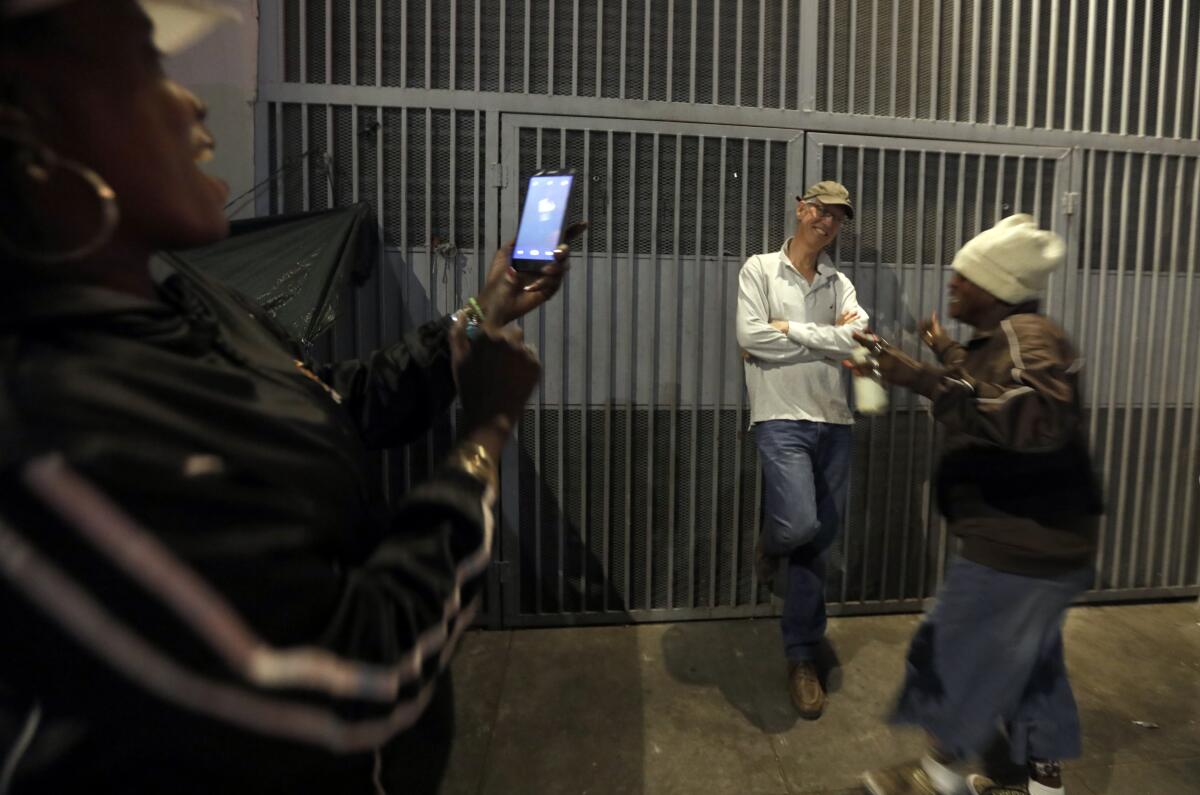

Broadway Place wasn’t the only encampment that Times photographer Francine Orr and I visited, but it was the most welcoming. Residents pulled out chairs for us. Some invited us into their tents, and when, occasionally, stares turned to hostility, we kept walking.

Encampments are accustomed to media dropping in, and even homeless individuals know the value of a soundbite. But we didn’t just drop into the lives of the residents of Broadway Place. We returned again and again over the course of eight months (and another eight months once they moved into their apartments) to track the Encampment to Home initiative and its aftermath.

The push to clear these sidewalks — a wholesale relocation with a deadline — was more ambitious than anything the city or county had tried in years, and to capture that, we lingered, to use one of Francine’s favorite phrases.

More than 30 years ago, encampments like these began to make news throughout the county. Built of plywood and cardboard, the small municipalities were given names — Tent City, Justiceville — and invariably decried as mean and shabby. Often they were razed.

Today’s encampments are no less squalid. Only now they are ubiquitous.

After visiting with Big Mama and her neighbors, I would drive through skid row, past tent camps that made Broadway Place and 39th Street seem almost suburban in their tidiness, and I was overwhelmed by what I saw.

Los Angeles, once celebrated for making dreams real, was no different from any other city in the country.

Homelessness lies at the center of a long-standing debate in American society that has hardly been resolved. That debate goes back to the 1930s when senators labeled Social Security socialism. It goes back to the 1960s when liberals and conservatives argued over the programs of the Great Society, and again, years later when President Obama pressed for passage of the Affordable Care Act.

The debate can be summed up in one question: Is government responsible for the health and welfare of its citizens?

Three years ago, voters in the city and county of Los Angeles gave their answer by taxing themselves to support the work of agencies responsible for building affordable housing and helping the homeless. But even then, some were skeptical that it would work.

While some might say many homeless individuals prefer the freedom of their life — the sidewalk their front porch, open to conversations, handout and hustles — the truth is no one wants to live on the street. But not everyone wants to take the steps to get into housing.

The process is slow, frustrating and not always a sure thing. Suspicious of agencies, wary of paperwork, unwilling to change their routines, some of the residents of Broadway Place and 39th Street stayed put. (Most impressive, though, were the efforts of outreach workers who helped the homeless navigate the bureaucracies designed to help them.)

By offering housing to everyone in these encampments, Encampment to Home was breaking with past efforts that have favored those in greatest need. Some will question either that decision, given the city’s housing shortage, or the selection of these particular encampments, out of thousands of others. The questions are fair: These residents of Broadway Place saw their lives changed on the merits of being in the right place at the right time.

But it is important to realize that homelessness is not a monoculture. It can change anyone’s life: those with severe mental illness and those exhibiting no greater disability than sleeplessness and fatigue. Assessing need is like assessing compassion; with so many variables, it cannot always be measured.

So what entitles the homeless — all the homeless — to housing? Some residents told me they had worked for it by going through all the paperwork, and one was fiercer in her opinion. “Don’t we all deserve to have a roof over our heads?” she asked. “Why do you want to see somebody suffer? That’s evil.”

As a bottom line, you cannot do better than that. No one deserves to suffer.

With the residents of Broadway Place settled into their apartments, Francine and I watched as habits and behaviors from the street moved indoors as well, so that living in an apartment became in some cases even more challenging than being homeless. Domesticity is a reflex, drawing upon childhood lessons, old memories and popular culture, and not everyone has those frames of reference.

Some argue that subsidized housing is its own worst enemy. They cite “moral hazard,” the theory that recipients of handouts have little incentive to maintain their property or behave responsibly when someone else is footing the bill. Though I saw evidence of disregard, I didn’t come away with the impression that it was related to society’s largess.

As one social worker told me: “For many they are leaving behind police, rape, eating out of trash, prison or bullets passing over their heads, and now they need to be reconditioned. They have to learn how to dream.”

But dreaming isn’t always easy. It means putting aside the trauma and the disappointments of the past and imagining a new life. Counselors can help — and the apartments had them — but that responsibility lies with the residents.

Sitting alone one afternoon in the apartment courtyard, I felt a surprising sadness. The building was quiet, music and voices muffled behind so many closed doors. The community that I had gotten to know on the street felt diminished, less tribal, more normal, I suppose.

Inside their apartments, away from the distractions of the street, residents had to face the causes of their homelessness and try to find a place in a world that had overlooked them for so long.

They struggled to pay bills, get along with new neighbors, stay healthy, find work. Their lives, as battered and scarred as they were, suddenly were no different from anyone else’s, and the future was theirs to either win or lose.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.