Latinos hope George Floyd protests bring focus on police violence in their community

- Share via

You don’t know these names, but Alejandra Merriman does.

She wrote them on a piece of poster board and held it as she marched to demand justice: Frank Mendoza. Anthony Pacheco. Martin Escobar.

A purple-inked chain linking dozens of names of Latinos killed by law enforcement in Los Angeles since 2000. And then there was the latest name, the reason she was out there marching alongside hundreds of others. The one belonging to Andres Guardado.

“In the brown community, we’ve always been taught by our parents to keep our head down and keep pushing. But our generation, my generation … we’ve had enough,” Merriman said. “We need to speak up for our own people. We can’t rely on others to speak up for us. We need to come together.”

Protests in the wake of the killing of George Floyd — a 46-year-old Black man who died after a Minneapolis police officer knelt on his neck while he was begging for air — conjured up the centuries-old past of brutality against Black Americans, centered specifically on the issue of police brutality.

It has also helped energize efforts by Latinos, the largest minority group in the U.S., to use some of that momentum to draw attention to deaths of Latinos by police.

For Latino organizers, getting any kind of traction on these issues has been hard. They say the names of the dead don’t stick in the public’s memory. They rarely lead to large protests and national movements.

The reasons, advocates and experts say, are numerous: media coverage that focuses strongly around immigration, a national leadership vacuum among Latinos on this issue and the fact that in some parts of the American Southwest, including L.A., Latinos make up a sizable portion of law enforcement. In the Los Angeles Police Department, half of the officers are Latino, making it by far the largest group in the department.

And when Guardado, an 18-year-old, was shot five times in the back in a Gardena street, it was a Latino L.A. County sheriff’s deputy who pulled the trigger as Guardado lay on his stomach. The killing generated national attention — and protests — in a way that almost no other shooting of a Latino had in years.

At some protests, the influence — and inspiration — of Black Lives Matter is hard to miss. Signs in solidarity with that movement, many held by Latino protesters, are hoisted high.

“I think we as a Latino community owe a great gratitude to the Black community and to the Black Lives Matter movement,” said Julissa Natzely Arce Raya, an author who has been sharing Guardado’s story on social media. “Because of the work that Black organizers have done and the Black community has done to bring forward police brutality and police killings, really to the national consciousness of America, we are starting to wake up to that same reality. ... In many ways, the Black community has shown us how to organize and speak out for our community.”

Latinos are no stranger to police brutality in a city in which they now make up almost half the population.

In 1943, during days-long attacks by white military servicemen against Mexican Americans in East Los Angeles and downtown, in what became known as the Zoot Suit Riots, the police looked on and then arrested mostly Latinos.

During the “Bloody Christmas” of 1951, there was the unprovoked beating of seven prisoners — most of them Latino. The beatings, dramatized in the 1997 film “L.A. Confidential,” resulted in the first grand jury indictments of serving LAPD officers and the first criminal convictions for use of excessive force in the department’s history.

At the time, Centro Community Service Organization, a Boyle Heights grass-roots group, was part of the fight to indict the officers.

As the years passed, Centro CSO focused its attention on immigrant rights and education, said Sol Marquez, an organizer with the group. But then, in 2016, came a rash of killings of Latinos by police in Boyle Heights and the focus shifted once more to police brutality.

“It was horrible and such a slap in the face of all of us that we had to take up the campaign to bring these cops to be jailed or something to happen to them,” Marquez said.

The group gained greater attention earlier this year, after video showed an LAPD officer beating a homeless man. Centro CSO is pushing for the officer, Frank Hernandez, to be fired.

Merriman began researching police brutality against Latinos after learning about the death of Michael Ramos, a 42-year-old fatally shot by an Austin, Texas, police officer in April. It prompted the 30-year-old to join Centro CSO.

She compiled the names on her poster board from a Times database published last month that showed that since 2000, there have been nearly 900 killings by local police that were ruled a homicide by county medical examiners.

Almost all of the dead were men, nearly 80% were Black or Latino. In nearly all cases, the use of force was deemed legally justified by the L.A. County district attorney’s office, which conducts an investigation into each death. Since 2000, only two officers have been charged as a result of shooting a civilian while on duty.

Juan Cartagena, president and general counsel of the legal advocacy group LatinoJustice, cited multiple factors for why killings of Latinos by police have not garnered as much attention.

According to Cartagena, some of those factors include mainstream media focusing on immigration as the biggest concern for Latinos, “an inability to talk about criminal justice policing beyond a Black-and-white binary in the U.S.” and the lack of institutions in the Latino community, such as churches, pushing hard on such issues like in the Black community.

“We don’t have the reverend on a Sunday saying, ‘We’ve got to stop these killings,’” Cartagena said.

Cartagena stressed the need for the Latino community to stand in solidarity to stop the killing of Black people, something that he said would go a “long way to address the issues we have with Latinos too.”

“At the same time, we cannot lose sight of the fact that police abuse also kills our own [people],” he said. “It is important for us to recognize this moment. Because we are at a cusp of significant debate about policing as a concept.”

On June 21, hundreds of people gathered for a three-mile march from Gardena to the sheriff’s station in Compton to protest the killing of Guardado. They held signs that read “Latinos for Black lives” and “Black Lives Matter.”

Najee Ali, a longtime civil rights activist in South L.A., attended the protest to offer support.

“As much as we’ve been saying Black Lives Matter … and they do, well hell, Latino lives matter too.”

But that’s a term that Latino organizers are careful to avoid, not wanting to take away from the Black community’s “plight for justice,” said Ron Gochez, a member of Unión del Barrio, which organized the protest.

“We don’t use brown lives matter, Latino lives matter,” he said. “We support the Black community.”

Unión del Barrio, which began in 1980, has long held marches and protests for immigrant rights and against police brutality and gentrification. A few weeks before the June protest, the organization held a caravan in Compton that grew to be more than 10 miles long and ended at the LAPD headquarters.

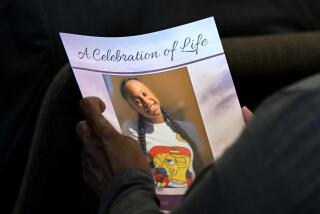

The Sheriff’s Department has said that Guardado was shot and killed around 6 p.m. on June 18, after two deputies saw him speaking to someone in a car blocking the entrance to an auto body shop on West Redondo Beach Boulevard. Investigators said Guardado “produced a handgun” and ran away, and that deputies chased him, before one shot him.

Earlier this month, the L.A. County coroner’s office determined that Guardado was shot five times in the back. Guardado had surrendered and was lying facedown on the ground when a Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputy who had been chasing him down a driveway holstered his weapon and approached the 18-year-old to put him in handcuffs, the deputy would recount.

Suddenly, according to this account, Guardado reached for the gun he’d moments before agreed to drop, which was still on the ground above his right hand, prompting the deputy to redraw his weapon. The deputy fired six rounds, five of which struck

Guardado in the back, killing him.

The narrative of Deputy Miguel Vega, provided to The Times through his attorney, raised fresh questions about the tactics used during yet another deadly police encounter.

Guardado’s case garnered attention rare for police shootings of other Latinos, with Ice Cube and Kim Kardashian sharing the case on their social media. In June, several public officials called for an independent investigation into Guardado’s death, including Sen. Kamala Harris (D-Calif.) and U.S. Reps. Nanette Barragán (D-San Pedro) and Maxine Waters (D-Los Angeles).

Last month, Melina Abdullah, one of the leaders of Black Lives Matter, stood amid a growing crowd in front of the Hall of Justice. People held signs that read “Black and brown unity” and “Tu lucha es mi lucha.” Your struggle is my struggle.

They were there not only to call for the ouster of L.A. County Dist. Atty. Jackie Lacey but to honor those who were killed by law enforcement.

“We will get justice in their names, because we can’t get justice for them,” Abdullah said. “Justice for Andres Guardado would mean that he is still here.”

In addition to reciting the names of Black lives lost, including George Floyd, Tamir Rice and Rayshard Brooks, Abdullah also called out Anthony Vargas, Guardado, Eric Rivera, Jesse Romero, Cesar Rodriguez and Christian Escobedo.

Gochez said it was “too early to tell” if Guardado’s shooting could be a tipping point.

“But I think,” he said, “there’s something in the air about change.”

Times staff writers Alene Tchekmedyian and Ben Poston contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.