Monster firestorm brings death and devastation back to area hit by California’s worst fire

- Share via

SACRAMENTO — Less than two years after the most destructive fire in California history tore through Paradise, the same region was under siege from a second monster firestorm that quickly grew to more than 250,000 acres, sweeping through mountain hamlets and killing at least three people.

On Wednesday night, Butte County Sheriff Kory Honea once again faced the grim task of announcing victims of the flames, just as he had for weeks after the destruction of the Camp fire.

Southern California is being engulfed by smoke and unhealthful air from fires up and down the West Coast.

Three bodies were found in the wake of the Bear fire, part of the massive North Complex blazes that raced through northern Sierra Nevada foothills before dawn Wednesday. The multiple blazes caught crews and residents off guard as they leaped southwest towards towns in Butte County, including the community of Paradise, which was largely destroyed by the 2018 Camp fire that killed 85 people.

The fires staggered a county still grieving the earlier catastrophe and besieged a state with unprecedented wildfires burning from Mexico to the Oregon border.

“We cannot underestimate what they can do to the community and what they can do to the people we love,” Honea said.

With the speedy advance, the North Complex fires, which had been burning since a barrage of lightning strikes hit the region Aug. 17, grew by 80,000 acres overnight, forcing fire officials to divert thinly stretched resources to yet another disastrous blaze.

With so many fires burning, millions of people in the Bay Area, Central Valley and parts of Southern California are breathing dangerous levels of particle pollution.

Across the state, 28 major wildfires have prompted more than 64,000 people to evacuate, said Daniel Berlant, a spokesman for the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection.

Fortunately for crews and residents in Southern California, Santa Ana winds were not as strong as forecast, and three major fires burning in Los Angeles, San Bernardino and San Diego counties did not grow substantially.

But in Northern California, some 20,000 residents in Plumas, Butte and Yuba counties were forced to flee the North Complex fires, which exploded in size to 254,000 acres overnight.

Fire officials on that incident and the Creek fire to the south struggled to get an exact footprint of the flames because high pressure kept the intense smoke, now blanketing almost the entire state, close to the ground.

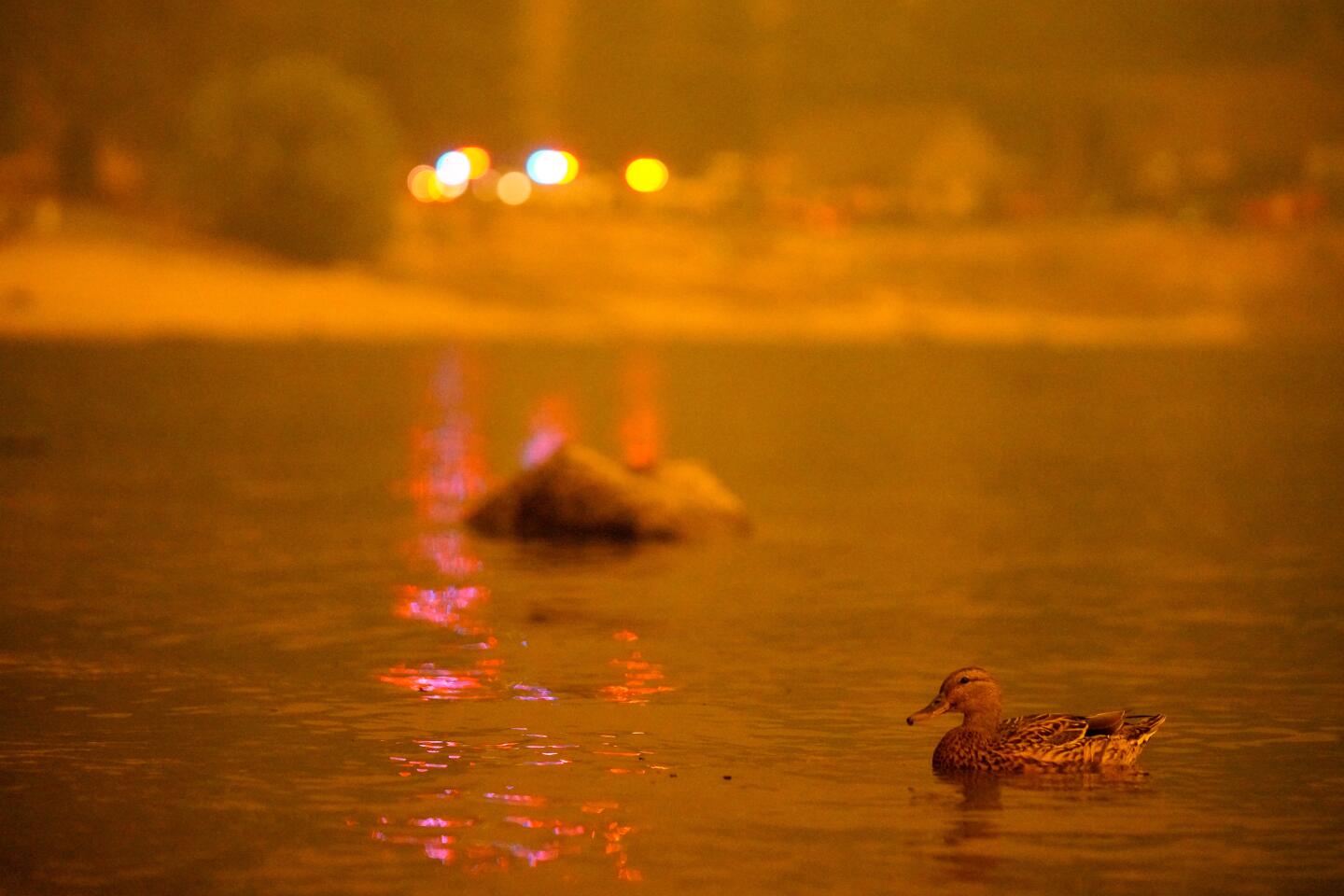

The skies around the Bay Area and other parts of Northern California took on an eerie glow as smoke from several fires enveloped the region.

The gray shroud made it unsafe for pilots to drop retardant and water or surveil where the fires had been and where they were going.

“One of the things we’ve seen statewide is with all the smoke, we can’t get a good assessment,” said Chris Vestal, a spokesman for the Creek fire response in the Sierra National Forest.

Embers stormed across miles of rugged, dry terrain in minutes, sparking new fires and creating a high-speed, fast-morphing footprint difficult to read on the ground.

“Right now it’s just a challenge without having air support,” Vestal said, “from a suppression standpoint and observation standpoint.”

When aircraft are in use, he said, fire commanders use “those retardant lines to give us an actual idea of where we’re going to put our bulldozer lines.”

“Being able to see it puts people in the most advantageous spots,” Vestal said.

The Butte County sheriff announced the deaths of three people Wednesday as fires continue to rage through a region already devastated by the Camp fire two years earlier.

On Wednesday, crews on the Creek fire were left to work with ground tools in areas of better visibility, mostly on the southern flank, closest to foothill towns such as Prather, Auberry and Clovis in the flatland, where winds were light. Ash rained down throughout the day.

The forest that surrounds them carried up to 2,000 tons of burnable timber per acre, most of it dead and dry from a bark beetle infestation that grew quickly in the Sierra during a drought that began in 2012.

(For comparison’s sake, the fires in Southern California are churning through about 14 tons of chapparal and grass per acre, consuming a lighter, quicker-burning fuel than the conifers and oak trees of the Sierra.)

Mark Van Aacken was surveying his community’s damage along Shaver Springs Road on Wednesday with the help of a local firefighter who helped him and a friend through the roadblock. It was an intel mission more for his neighbors than himself. He knew his house was gone. A firefighter showed him a photo the night before.

“But still a picture doesn’t do it justice apparently,” said Van Aacken, 40. “Seeing it firsthand is kind of another situation. I’m kind of bummed my wife isn’t with me to see it at the moment.”

They were seeking fresh air, solitude and life away from coronavirus lockdowns. Instead, they got caught in a firestorm, some rescued by helicopter.

Van Aacken and his wife moved to Auberry almost four years ago from Arizona to be closer to family in the area and to settle down and raise their twin 7-year-old daughters in the great outdoors.

“It’s been great, four-wheeling all the time … just being in the outdoors away from the city life,” he said. “It’s always like camping — it’s the small town, you know?”

The family has kept tabs on the state’s rash of fires over the last month and knew their area was at risk, so they evacuated as soon as Fresno County sheriff’s deputies knocked on their door and told them to leave.

“I feel like we’ve just gotten away with it every year,” Van Aacken said. “So I feel like we were a little relaxed about the fact that every tiny fire that came up they dropped so [many resources] on it we never thought it’d be that big an issue.”

His brother lost his home too. But across the road, his father’s still stood.

“We were just hoping at least one of the homes was still standing,” he said.

California’s record-breaking wildfires continued to rage Tuesday even as authorities conceded they would get worse with downslope winds from Shasta to San Diego.

The North Complex fires are burning through similar, heavily wooded terrain. The incident now stands as the ninth-largest wildfire in California history, one more dismal statistic in this record fire season; the second, third and fourth largest were started by the same August lightning storm.

Photos showed devastation in the tiny Butte County hamlet of Berry Creek, where many homes and other structures were destroyed. Officials said they don’t know the extent of the destruction in the town, which is north of the Oroville Dam.

Jay Kurth, incident commander for the U.S. Forest Service, said the agency was still working Wednesday morning to “figure out where the fire footprint really is” because of the extreme overnight activity.

Paradise and Concow were placed under evacuation warnings, and orders were issued for other areas around Lake Oroville.

Frank Martinez, 55, lives in the Mount Ida neighborhood of Oroville, at the base of the mountains, and has numerous friends in Berry Creek. Tuesday afternoon, as the Bear fire closed in on that town, more than two dozen relatives and friends fled their homes there and headed for Martinez’s 1.5-acre spread for refuge. Martinez said that by that time, flames were already threatening a bridge on the evacuation route, backing up about 100 cars. The caravan became separated, with some vehicles stuck on the road as Cal Fire worked to clear the passage.

Just hours after some of his friends reached his house, news came that Martinez might have to leave as well. Around 10 p.m., “it was like all of the sudden someone turned on a switch” and the wind became “crazy bad,” he said.

By 1 a.m. Wednesday, the evacuation warning for Martinez’s neighborhood had turned into an order, forcing him, his eight rescue dogs and other refugees to head into more urban areas of Oroville. He has been told his house has been destroyed, he said Wednesday, “but I can’t believe it until I see it.” He knows of at least about 25 friends who lost homes in Berry Creek, and he said the school, church and local bar also burned.

In 2017, Martinez was informed that he had lost his home in the Wall fire, but that turned out not to be true, though flames came just two feet from his propane tank before firefighters beat them back, he said. In 2018, when the Camp fire destroyed the nearby town of Paradise, his Berry Creek friends again took shelter on his property. Though 85 people died in the Camp fire, making it California’s deadliest blaze, Berry Creek was spared. “We are veterans of this,” he said.

So, for his house, “I am keeping my faith and I’m keeping my hope alive,” he said. “Basically we don’t know until they lift the evacuation orders.”

Times staff writer Luke Money contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.