San Franciscans question George Gascón’s legacy as ‘godfather of progressive prosecutors’

- Share via

Adriana Camarena abhors the idea that George Gascón is being touted as a reformer in the nationally watched contest for control of the Los Angeles County district attorney’s office.

The Bay Area organizer spent years leading rallies against Gascón in San Francisco, and her voice rises with annoyance as she rattles off the names of men killed in controversial police shootings during Gascón’s time as district attorney: Mario Woods, Luis Gongora Pat, Amilcar Perez-Lopez, Alex Nieto.

Although each of the men Camarena named was armed, their cases sparked public outcry and raised questions about Gascón’s commitment to holding police accountable after he failed to prosecute the officers involved. Camarena said Los Angeles activists, who quickly embraced Gascón, should be more skeptical of the so-called “godfather of progressive prosecutors.”

“I understand why they want a change, but I would say they are not going to get a change,” Camarena said. “They are going to get somebody who is a career officer who has nothing to show as a progressive prosecutor.”

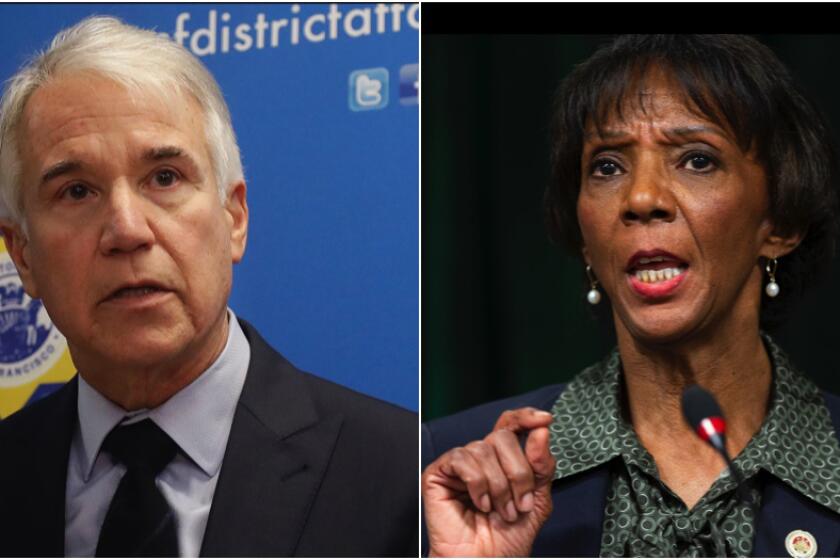

A champion of alternative sentencing, diversion programs and reducing prison populations, Gascón had a tenure in San Francisco that earned him praise and endorsements from criminal justice reformers and national progressive leaders, including Sens. Kamala Harris, Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren. But as Gascón tries to oust Los Angeles County Dist. Atty. Jackie Lacey in a race that many see as a flashpoint in a national debate about criminal justice, the impact of his policies in San Francisco are under a microscope.

The November contest between Los Angeles County Dist. Atty. Jackie Lacey and former San Francisco Dist. Atty. George Gascón to oversee the nation’s largest prosecutor’s office has been framed as a test of appetites for criminal justice reform.

In San Francisco, a number of activists, law enforcement officials and local leaders offer less-glowing reviews of Gascón. Mayor London Breed has endorsed Lacey, and the city’s police union is one of many in the state spending millions to derail Gascón’s campaign. Some of Gascón’s former constituents argue that his diversion programs for low-level offenders removed the threat of punishment, driving a historic surge in property crime and car break-ins. Others, like Camarena, said his progressive reputation is more myth than reality.

Gascón insists that frustrations with him in San Francisco largely stem from resistance to his reform initiatives. Residents, he said, were poisoned against him by police unfairly blaming Proposition 47 — the landmark ballot initiative he co-authored that reduced several felony crimes to misdemeanors in California — for the city’s struggles with auto burglaries, homelessness and drug use.

“It’s very, very hard when a community is being bombarded every day by Officer Friendly telling them the reason we have a homeless person on the corner … is because of Prop. 47,” he said. “It’s a very powerful PR machine that is relentless.”

San Francisco’s property crime rate jumped 37% during Gascón’s tenure, driven largely by record numbers of car break-ins. In 2017, the city reported more than 31,000 auto burglaries, the worst year on record, according to the San Francisco Chronicle.

A 2018 Public Policy Institute of California report found a link between the passage of Proposition 47 and increases in property crime and larceny. But one of the authors of that report, Magnus Lofstrom, cautioned against blaming all of San Francisco’s ills on Gascón’s signature policy initiative. The city’s population rose significantly during Gascón’s tenure, and increased tourism and wealth could have created more opportunity for auto burglars, Lofstrom said. Additionally, San Francisco police rarely, if ever, arrested suspects in car break-ins as they surged, the Chronicle reported.

Randy Shaw, head of the Tenderloin Housing Clinic in San Francisco, said he supported Proposition 47 but believes Gascón’s policies were disastrous for the low-income neighborhood where he has tried to give aid to the homeless for decades.

“He made no effort to deal with the drug and crime problems in the Tenderloin — none, zero. That might be generous. He might have been worse than zero,” Shaw said. “He discouraged the police, because at some point they decided, what’s the point in making these arrests, because he isn’t going to prosecute them.”

Gascón’s prosecutors filed criminal charges in about half the felonies and 40% of misdemeanors presented to his office from 2011 to 2019, records show. But Gascon and his allies argue that the filing numbers show only a partial portrait of his record.

The filing rates do not capture instances in which prosecutors went after defendants for a probation violation rather than pursuing a new charge, according to Alex Bastian, a spokesman for the San Francisco district attorney’s office. Taken together with filings, prosecutors “took action” in 59% of felonies and 54% of misdemeanors, records show.

In his bid to become L.A. County’s next district attorney, George Gascón has touted his record as a reformer. While many praise his history, questions are being raised about his handling of LAPD.

Such tactics infuriated police officers, who said they felt like they were arresting the same people multiple times because of Gascón’s reluctance to open new cases.

“They would dismiss the new case and file on the motion to revoke [probation],” said Tony Montoya, president of the San Francisco Police Officers Assn. “When you’re on probation, there’s supposed to be some deterrent to continue down the path that got you on probation. Now, there wasn’t.”

Roughly 10% of all misdemeanors brought to Gascón’s office during his tenure were handled through a diversionary program called Neighborhood Courts. Launched in 2012, the program aimed to hold low-level offenders accountable without saddling them with a criminal conviction.

Defendants in such cases would meet with community volunteers and be offered “directives” to make amends for their offense; these could include entering a drug treatment program or completing a community service regimen. As a result, the defendants would avoid a conviction, which Gascón hoped would reduce the likelihood they would reoffend later in life.

He was also a leader in a statewide movement to eliminate cash bail, using a risk evaluation based upon several factors — including a defendant’s criminal record, employment status and the severity of the offense with which they had been charged — to determine the likelihood they would appear in court, instead of making their pretrial release dependent on their financial situation.

Taken together, the efforts seem to have accomplished Gascón’s goal of cutting back on the use of prisons and jails. Records show that San Francisco’s average daily jail population fell by about 27% during his tenure, from 1,746 in January 2011 to 1,271 in October 2019, when he resigned to challenge Lacey.

Brian Pearlman, who oversaw misdemeanor cases for the San Francisco public defender’s office during Gascón’s tenure, said he believes the programs were a lifeline for a number of first-time offenders and drug-addicted defendants who needed to see the inside of a treatment center rather than a jail cell.

“I saw so many people who went through that process finally seeing that system caring for them. … I saw a lot of people work their way out of the criminal justice system into housing and help,” he said.

But Lorraine French says her life, too, was forever changed by Gascón’s progressive policies. The 80-year-old holds him partially responsible for the 2017 murder of her younger brother during a robbery involving a man who had been granted pretrial release under the risk assessment tool Gascón championed.

Lamonte Mims, who was already on probation when he was charged with gun possession that year, was released after an evaluation found him to be a medium public safety risk. Lorraine’s brother Edward was taking pictures in the city’s idyllic Twin Peaks area when he was shot and killed while Mims and a companion allegedly robbed him of his camera.

Mims was charged in the killing, though he did not pull the trigger. Officials later said a data error led Mims to receive a lower “public-safety assessment” score than warranted, but the slaying raised questions about the tool used to evaluate him. French demanded a meeting with Gascón, during which the district attorney offered his condolences but then began “screaming” at her as she challenged him about the evaluation’s role in her brother’s death, she said.

“When he started yelling at us, I said, George … if you can’t do your job, then quit,” French said. “You chose to be the DA. We have the right to question you.”

Gascón denied that he yelled at French. Although he remains horrified by what happened in the Mims case, Gascón said, one tragic outlier does not invalidate the broad successes of the program. The same assessment tool, based on algorithm scores, is used in dozens of jurisdictions across the U.S., including L.A. County, where the courts last year received a grant to launch a pilot program with the tool.

“Just like there are times when people go out on bail and commit horrendous things … a real tragic event occurred when a young man was released without bail, and he went on to murder someone, and that weighed very, very heavily on me,” Gascón said.

For some, frustration stems from Gascón’s rhetoric not lining up with results. Although his office filed misconduct charges against dozens of police officers, his refusal to prosecute police in fatal force cases has been criticized in the wake of nationwide protests over the police killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor.

The decision not to file charges against officers in the 2015 shooting of Woods, a 26-year-old stabbing suspect who was under the influence of methamphetamine, has hung heaviest over Gascón throughout the campaign. Bystander video appeared to show Woods, who was holding a knife, walking away from officers when he was shot. Police say Woods ignored orders to drop his weapon before officers opened fire.

At the time, Gascón said the officers “would have been derelict in their duty to protect the public had they let Woods escape.” His decision was heavily criticized by then-Public Defender Jeff Adachi and John Burris, the civil rights attorney who represented Woods’ family.

About five months later, officers in the city’s Mission District shot and killed Gongora Pat, a homeless man who advocates said was suffering a mental health crisis. Police responded to reports of Gongora Pat waving a knife but found him seated when they arrived at the scene. When he refused to comply with orders to drop the weapon, an officer shot him with a beanbag round. Police allege that Gongora Pat then got up and marched toward an officer with the blade in his hand, and two of them fired a volley of fatal gunshots.

The encounter lasted less than a minute, and many have criticized the officers for failing to de-escalate the situation, claiming the decision to shoot a less-lethal round at Gongora Pat while he was on the ground provoked the deadly incident. Gascón decided he could not prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the officers were criminally liable.

Gascón, who did not prosecute any officers in on-duty killings during his eight years in office, has argued that he was hamstrung in many shooting cases in San Francisco by state law that severely limits when police can be charged in deadly force cases. He supported a 2019 Assembly bill that raised the threshold requiring that police use fatal force only when “necessary” instead of when “reasonable.” Under the new law, Gascón says, he would have charged the officers who shot Woods.

“It’s a very comfortable position for Gascón. This is what he always does,” said Camarena, who was a spokeswoman for the Gongora Pat family. “It always seems like the ball is never in his court.”

Gascón maintains he is more qualified than Lacey to confront officers who take lives unjustly, arguing that Lacey has declined to bring charges in far more egregious cases involving unarmed people. A review of San Francisco police records shows that the majority of shootings in which Gascón declined to prosecute involved suspects armed with guns, knives or blunt objects.

Despite the outcome of the Woods case, Burris said he believes Gascón is genuinely dedicated to police reform in a way most other prosecutors are not.

“I think he wants to do it. I think his philosophy certainly is there; his legal philosophy and his commitment to social justice certainly seems to be there. I never doubted it,” he said.

Hillary Ronen, a member of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, had been critical of Gascón’s record on police shootings but ultimately endorsed him. Making enemies of activists and police unions shouldn’t be considered a flaw on Gascón’s record, she said, but rather should be seen as proof of his independent streak.

“I worked very closely with him and believe him to be a very genuine and good person,” she said. “But I will tell you, he didn’t have a ton of good friends in San Francisco by the time he left.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.