- Share via

Kevin Brown didn’t do well under pressure.

Bullied as a child, anxious and depressed for much of his adult life, the 61-year-old retired police criminalist had suffered consequences at work and at home for failing to stand up for himself.

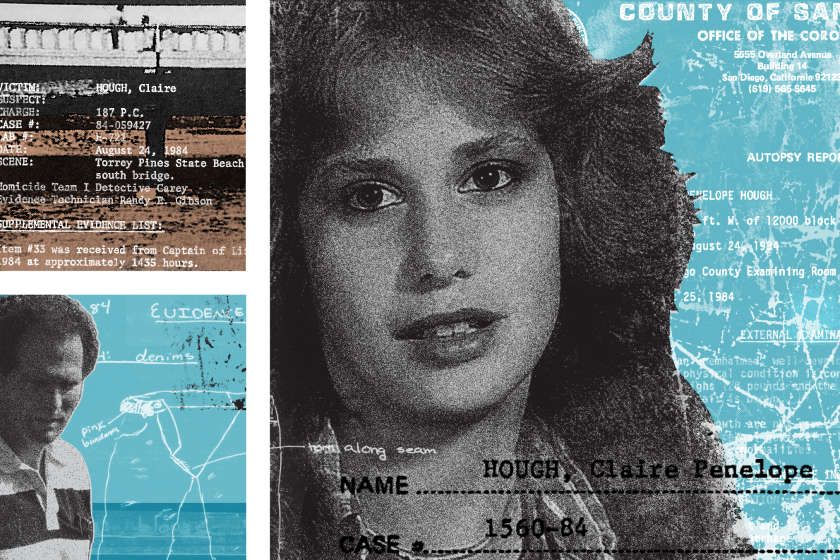

Now, unbeknown to him, he was in the crosshairs of two veteran San Diego detectives investigating the brutal murder of a 14-year-old girl at Torrey Pines State Beach in 1984.

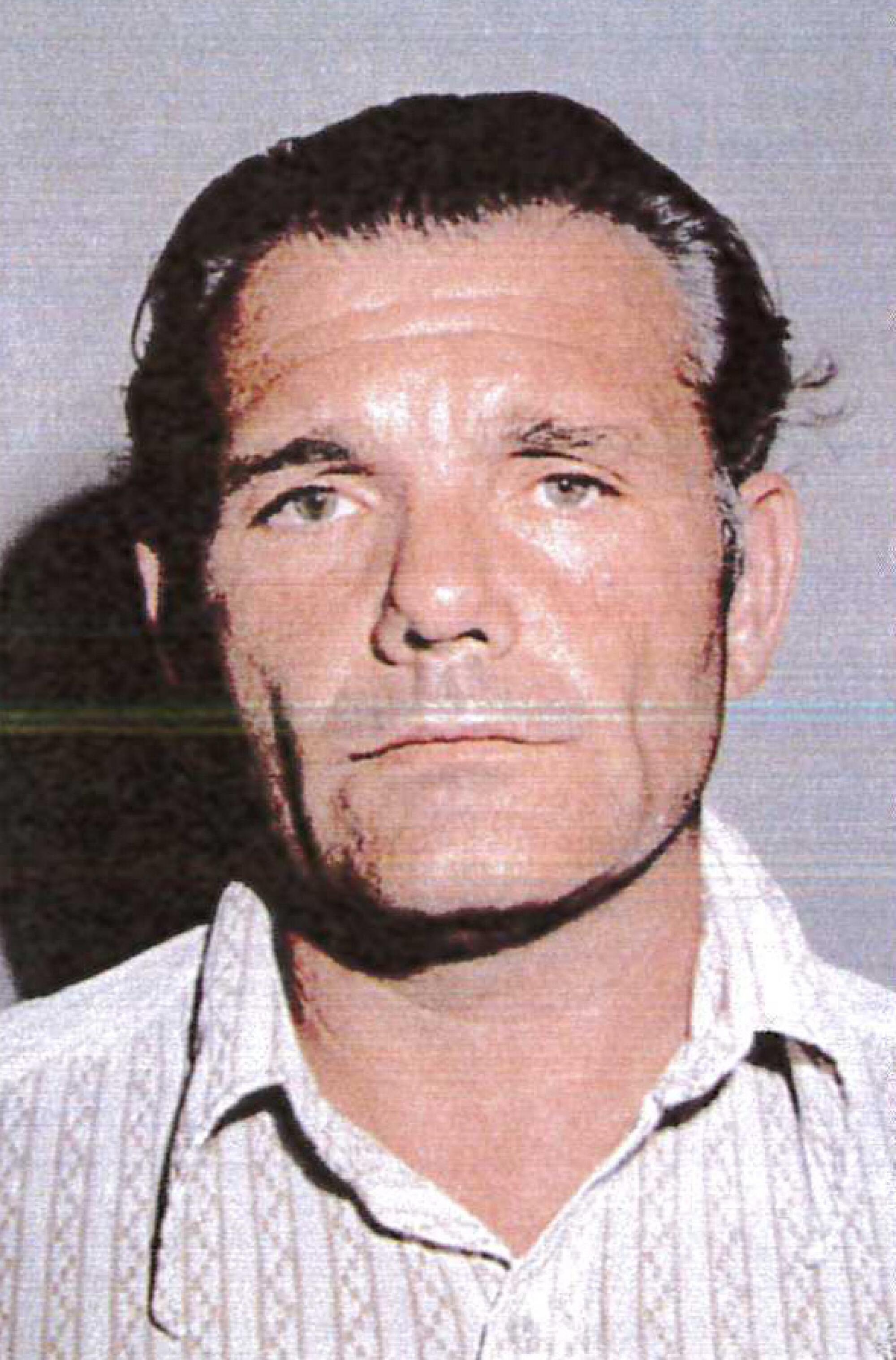

Recent DNA tests had identified Brown’s sperm cells on vaginal swabs collected during the autopsy of Claire Hough. The cold case detectives, Michael Lambert and Lori Adams, had spent a year quietly looking into Brown’s background and that of another man, Ronald Tatro, whose DNA had also shown up in the evidence.

Tatro was literally a dead end, though — drowned in a river in Tennessee in 2011. So the detectives focused on Brown.

On Jan. 9, 2014, they arrived unannounced at his Chula Vista, Calif., home and asked for his help on some old murders of prostitutes. This was a ruse to get inside and get him talking.

Brown had spent 20 years working in the San Diego police lab, leaving in 2002, 10 years before the DNA hit. His career there was cut short by poor performances during courtroom testimony. One of his bosses said defense attorneys would “beat him up pretty good” during cross-examinations, get him to back away from his findings.

Thirty years after Claire Hough was killed, a new round of forensic testing pointed to two suspects. One of them was familiar to the police.

The detectives spent a couple of hours asking about Tatro — Brown said he didn’t know him — and then steered the interview to Hough. They showed Brown her photo, and he said, “Oh, I remember her.”

“Did you ever meet her?” Lambert asked.

“No, not personally,” Brown said. “I just remember the picture looks familiar.”

Lawsuit seeks to hold detective accountable for criminalist’s suicide.

Police interrogations are like ladders: Rung by rung, detectives try to move a suspect uphill in the direction of confessing. They know that a suspect saying “I did it” can be powerful evidence. But confessions are also problematic; false ones are a leading cause of wrongful convictions.

Here, by acknowledging some familiarity with Hough, Brown had taken the first step up the ladder.

Her murder was big news when it happened, and it had been revisited in the media numerous times over the years, so Brown wasn’t the only person in San Diego who would have recognized her picture. But the detectives weren’t going to leave it at that.

They asked Brown whether he was the criminalist who analyzed the Hough evidence in 1984 — they already knew he wasn’t — and he said he couldn’t remember all victims in the cases he worked.

There was some discussion about how the lab was set up back then, before DNA tests came along and could identify suspects from the tiniest bits of blood, saliva and other bodily fluids.

Then Lambert dropped a bombshell. “The issue that we have with this case,” he told Brown, “is that in some of the evidence, your DNA showed up.”

“Who?” Brown asked.

“Yours,” Lambert said.

Brown said contamination must have happened: “I had my hands in a lot of things there.”

Detectives knew that Brown’s DNA was from sperm cells, but they didn’t tell him that, letting him wonder out loud if maybe he had touched her clothing or breathed over it while a criminalist nearby examined the evidence. He said they didn’t always wear masks or gloves.

Eventually he asked, “Do you know how it got — where my evidence is?”

“Yes,” Lambert said. “Your evidence was on vaginal swabs.”

“What?” Brown said.

“And it was sperm,” Lambert said. “It wasn’t touch DNA, it wasn’t saliva.”

The detectives sharpened their approach. “We know that you were there,” Adams said. “How else would your semen get inside her?”

“There’s only one way, Kevin,” Lambert said.

“I know,” Brown said. “I’m not that dumb.”

This would have been a moment for Brown to point out that criminalists commonly brought their own semen into the lab, deposited on pieces of cloth so it could be used to test the efficacy of sperm-detecting chemicals. But he didn’t.

Instead, he wondered out loud if someone planted his semen, although he couldn’t explain how that was done, or who would want to do it. Detectives told him contamination of any kind had been ruled out.

“Did you have sex with her?” Lambert asked.

“I don’t even remember if I did,” Brown said, adding a few minutes later, “I don’t know how ... I don’t remember ... I don’t remember every person I may have been sexually intimate with, but I do know that I’d never, ever kill anybody.”

The detectives brought up Tatro again, and offered possible scenarios.

“Maybe,” Lambert said, “you guys knew each other well enough that maybe you hung out together once in a while and you just happen to go to the beach at Torrey Pines that day and ran into a pretty young girl who was by herself and, ‘Hey, let’s party with her and hang out with her for a little bit,’ and then it turns into a sexual thing, whether it was consensual or not with her. And then maybe something just went wrong.”

“No, no, no, no,” Brown said.

“Maybe you know him,” Adams said, “but as you’re engaging in a sexual encounter with this young girl, he interrupts it and — and he’s a wacko and he’s freaking out. Now, he’s attacking and slashing and you’re like, ‘I’m just getting the hell out of here’ and you leave. And she turns up dead and now you’re terrified. I mean you just witnessed something horrific.”

Brown was quiet. Then he asked, “The spermatozoa that you have is mine?”

“Is yours,” Lambert said.

“You’re sure?”

“Absolutely.”

Digging a hole

Brown scrambled for explanations. He said back around the time Hough was murdered, he had anxiety issues during sex. “I had the inability to ejaculate,” he said. “I went through quite a few years when I wasn’t able to do that. So I find it hard to find my sperm there when I had that issue.”

He didn’t know it, but he was digging a bigger hole for himself.

One of the issues confronting detectives during their investigation was the low number of sperm cells found on the vaginal swabs. There were about 150 cells, according to the lab results, when a normal ejaculate has hundreds of millions.

They had theorized that maybe Brown had a low sperm count, or maybe he couldn’t fully ejaculate. And now, in the interrogation, he had offered up that answer himself.

Detectives pressed him further by talking about Hough.

“This is everybody’s daughter,” Adams said. “This is not some prostitute. This is not some throw-away girl that nobody cares about. Everybody that has kids can relate to this girl.”

Lambert: “She wasn’t a troublemaker. She was a good girl from a good family. She came out here to visit her grandparents and ended up being found on the beach.”

Brown: “I don’t know what to say. It wasn’t me. I don’t know how my sperm got in her and I didn’t do that.”

A few minutes later, his mother-in-law walked in. She lived in the house and had overheard something. “This sounds serious,” she said.

“Yeah,” Brown said. “Would you get John? Call John.”

John is John Blakely, Brown’s brother-in-law. He lived in the house too. He’s a defense attorney.

The interrogation was over.

But the detectives weren’t finished. They handed Brown a search warrant they had obtained a few days earlier. More than a dozen officers came in and began removing things and taking photographs. They were there for several hours.

The warrant authorized them to take computers, cellphones, diaries, photos, newspaper clippings, videos — items that detectives thought might show Brown and Tatro had been in communication over the years since the murder, or that Brown had been following media accounts of the Hough case, or that he had an interest in sadomasochism.

When they were done, they carted away 14 boxes, a suitcase and four trash bags — thousands of objects, many with little obvious connection to the case. They took cookbooks, a Bible, a copy of the Declaration of Independence, a signed photo of former President George H.W. Bush.

It would be up to the detectives to sort through it. But first they went to Mater Dei Catholic High School, where Brown’s wife, Rebecca, taught. They explained what was going on and asked her to drive home so her car could be searched too.

Standing in the school parking lot, Adams would later recall, she heard Rebecca Brown mutter this: “Boy, I sure know how to pick ‘em.”

A friend named Mike

Later that day, Kevin Brown left a message for the detectives. He wanted to talk some more.

This was unusual. “I don’t think I ever had a suspect ask me back before,” Adams said, “especially into their house.”

When they met the next morning, Brown said he’d been thinking, “trying to piece in my memory what might have happened in my life, and the name Claire kept popping up.”

He remembered an episode with a friend named Mike, “a hustler” who liked to go out and meet women. Brown couldn’t pinpoint when it happened, but he thought it might have been around the time Hough was murdered, almost 30 years earlier.

“Mike met these two girls,” Brown said, “and I believe one of them was Claire and — God, at the time they looked old enough.”

He said the girls were visiting from out of town and staying at a Holiday Inn near downtown San Diego. He and Mike got together with them several times over the course of a week.

He thought maybe they’d gone to Balboa Park and Pacific Beach, but he wasn’t sure. He believed he probably had sex with the one he thought was named Claire. Could she have been the one who wound up murdered later at Torrey Pines State Beach?

He couldn’t recall details about the girl, even after he was shown a photo of Hough again. “I just remember the word Claire and these two girls that we met,” he said.

The detectives were skeptical. Hough was staying with her grandparents in Del Mar Heights, not at a Holiday Inn in San Diego. She was 14 and didn’t have a driver’s license or access to a car. She wasn’t riding around town with strangers.

“I don’t believe we’re talking about the same Claire,” Lambert said.

He pressed Brown again on how he knew Tatro, maybe through strip clubs, prostitutes or photo sessions with nude female models. Brown said he didn’t know him.

The retired criminalist also tried to clarify his comments from the day before about sexual dysfunction. He said when he lived in New Mexico in the late 1980s, he was intimate with a woman who told him she had become pregnant. She wasn’t, but it spooked him so much that for years afterward, until he got married, he was afraid during sex to have an orgasm.

“I just didn’t want to have a baby,” Brown said.

He sensed that the detectives doubted his story. He offered to take a lie detector test. They drove him to a substation in the South Bay.

Polygraphs are controversial, their reliability so suspect that courts generally ban any mention of them during criminal trials. Scientists question whether the physiological changes measured by the machine — blood flow, sweat — are due to deception or to stress and other factors.

Brown was worried about the test. He had told the detectives earlier that he suffered from generalized anxiety disorder, a medical condition that left him flustered and inarticulate under pressure, and now he thought his nerves might betray him, make him look guilty.

“I am at a loss of words how my sperm got on a 14-year-old’s vaginal swabs,” he said. “For the life of me, I have no idea.”

‘This is not going to go away’

The polygraph results were mixed. According to the examiner, Brown was truthful when he said he had never hurt or killed anyone. The results were inconclusive when he said he didn’t know Tatro.

When asked whether he had sex with Hough or knew anything about her death, Brown’s denials showed deception, the examiner said.

After the polygraph, Brown seemed confused by the results. “I don’t know anything about this Claire,” he said. “I don’t even know where I would have encountered her. In my thoughts, I know I wouldn’t have killed her.”

“OK,” Adams said, “did something just go horribly wrong or maybe get a little rough and get out of control?”

“I’ve never done that with anybody,” Brown said.

The detectives pressed him again to explain the sperm DNA. “I don’t know how it got there,” he said. “Obviously, I must have had sex with her. I don’t know.”

Adams said, “OK, so we will at least agree that sex is the reason why it got there? Period. Sex is how that semen got there.”

Brown: “That’s the only way I can think of.”

But when Adams asked him for details on where and how he first encountered Hough, he was silent. He asked for his brother-in-law, the defense attorney.

Lambert said, “Kevin, I’m going to be honest with you. This is not going to go away.”

“I know,” Brown said.

The detectives tried to keep him talking, suggested again that maybe Brown wasn’t there when Hough was killed. A few minutes later, Brown asked for more information about the teen. He said it might refresh his memory.

“I don’t have the slightest clue what you’re talking about on this stuff,” he said. “But yet you’re right. I didn’t do well on the polygraph.”

Adams tried a different tack. “I may be out of line,” she said, “but I will say that I don’t believe for a second that you thought she was 14. I really don’t. I think she was probably a little bit more mature than most girls and probably acted a little more grown up than most girls. I don’t believe for a second that you would have known her age, her true age.”

“Well,” Brown said, “I didn’t.”

Tension at home

In the days following his police interrogations, Brown grew anxious and scared. Twice he had trouble breathing and his wife took him to urgent care.

Off and on throughout much of his life, first in New Mexico and then in San Diego, Brown had sought the help of counselors and doctors. They treated him for insomnia, anxiety and depression.

He traced the troubles to his childhood and being bullied in school. He told the doctors he was often uncomfortable in social groups and had difficulty asserting himself. He said those failures sometimes made him angry.

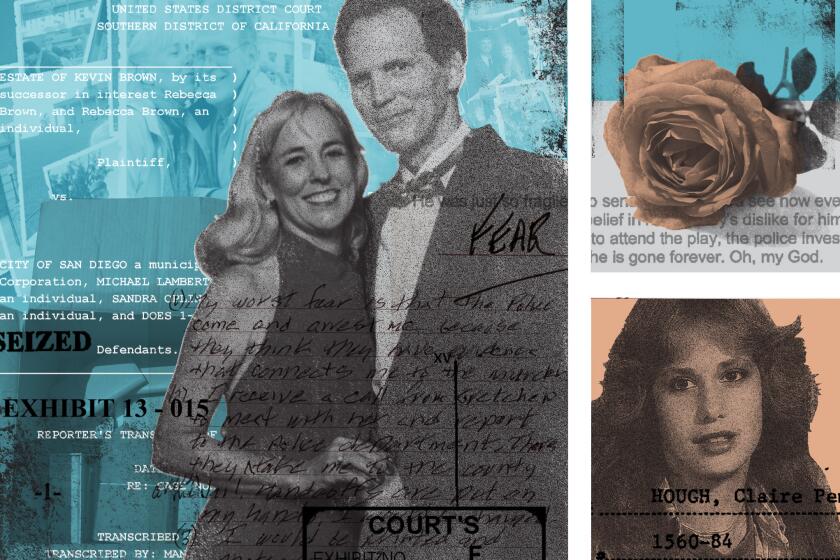

In February 2014, a month after police first contacted him about the Hough murder, Brown began seeing a new psychiatrist. He mentioned “legal problems” that were causing stress but didn’t specify what they were about.

Tensions ran high at home. Some of the things that had come up about Brown in the police interrogations — nude photo shoots, prostitutes, pornography — were news to his wife, Rebecca, who was there for part of the questioning. “It didn’t please me,” she said, although she was certain those activities had ceased once they married.

She and her 80-year-old mother, MarLynn Blakely, were also upset about the items police had seized during the search of the Browns’ home. Many were mementos belonging to MarLynn, who spent parts of her days leafing through photo albums, remembering. Now she couldn’t, and she let Kevin Brown know about it with her tears.

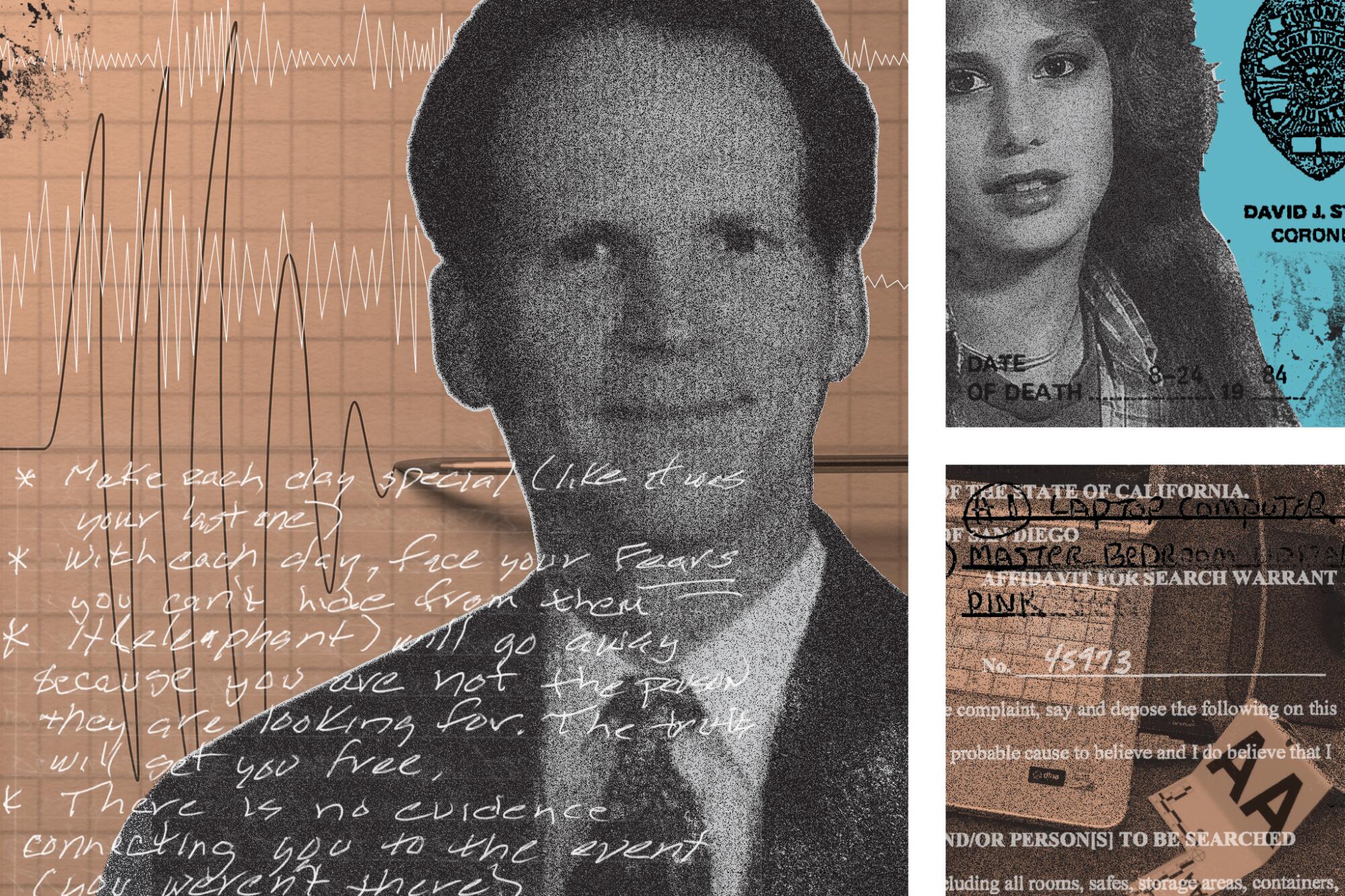

A month went by, then another. Brown lost weight. He couldn’t sleep. He wrote a note about his worst fears: that he would be arrested, kept in jail until trial, a year or longer. He would be behind bars, unable to relax, sharing space with prisoners who would harm him when they found out he used to work for the police.

“Being away for this time and being by myself is the part that scares me,” he wrote.

The Browns hired a defense attorney, Gretchen von Helms. They told her they believed contamination was the reason for Brown’s DNA hit. She advised them to be patient as detectives finished their investigation.

But waiting was hard. Rebecca Brown called Det. Lambert and asked him when they were going to get back the items taken by police. Soon, he told her.

In their minds, once the possessions were returned, the nightmare would be over. Police would know Kevin Brown had not been involved in the murder. He wouldn’t be arrested.

Lambert never told them that, but that’s what they believed. Kevin Brown started crossing days off on a calendar, each one a step closer to being cleared. When the stuff came back, they would celebrate. They made plans for a romantic getaway at a hotel in Imperial Beach.

Except the stuff didn’t come back. Rebecca Brown called Lambert again. Soon, he said. She called the next month. Soon. She asked him six or seven times.

Kevin Brown was keeping a journal, filling it with self-affirmations. On Aug. 26, 2014, he wrote this list:

* Make each day special (like it was your last one)

* With each day, face your fears. You can’t hide from them

* It (elephant) will go away because you are not the person they are looking for. The truth will set you free

‘Cat and mouse game’

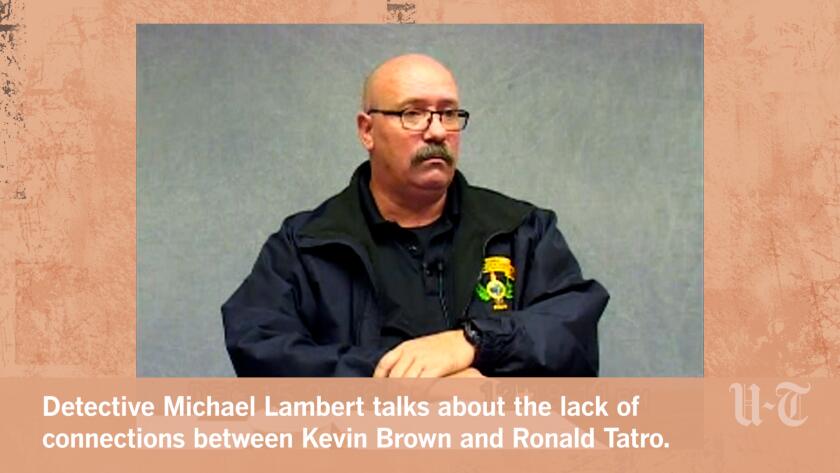

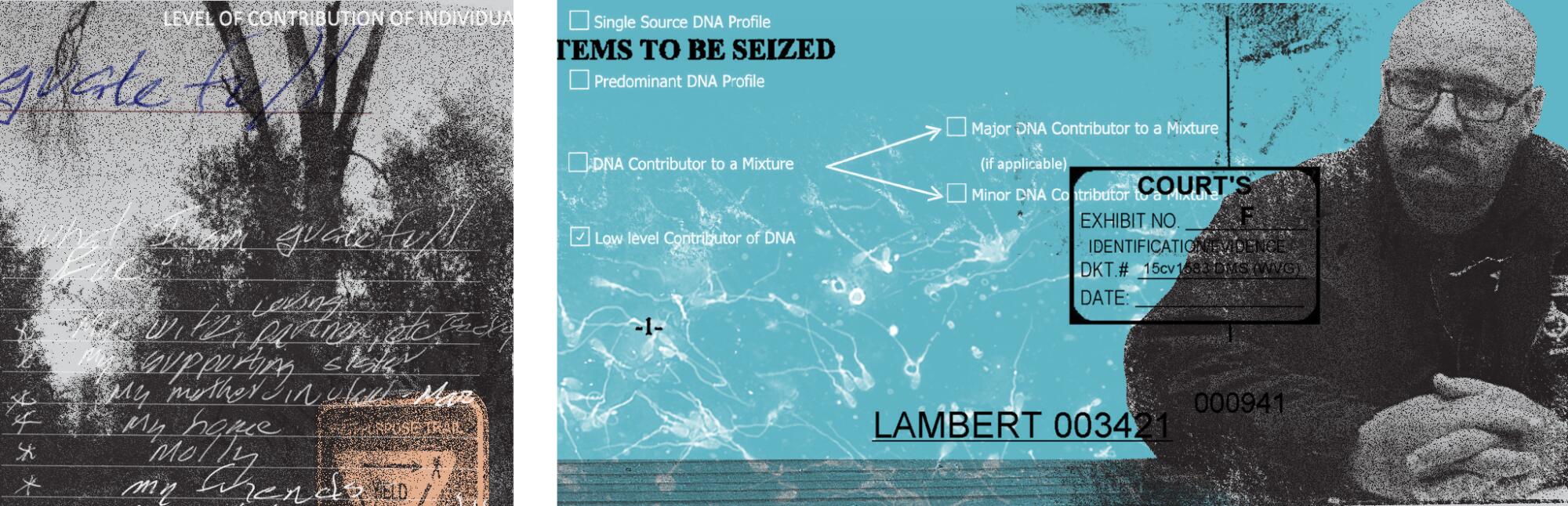

Lambert knew within three months of the search that none of the items police seized from the Brown house had anything to do with Claire Hough’s murder.

He dug through the boxes and bags himself. Nothing connecting Brown to Hough or to Ronald Tatro. Nothing showing Brown had any sexual interest in teenage girls, or in sadomasochism. Nothing indicating he had been keeping track of media coverage over the years of the murder.

There were other holes in the case the detective was trying to build. Lambert believed that because of the sperm DNA, Brown had assaulted Hough right around the time she was murdered. But tests found no other physical evidence tying him to her or to the place where it happened. No hairs, no fingerprints, no blood, no skin cells.

The only new discovery — DNA extracted in May 2014 from a pubic hair found on the victim’s bandana — pointed to Tatro, not Brown.

- Share via

Detective Michael Lambert talks about the lack of connections between Kevin Brown and Ronald Tatro.

Lambert came up empty trying to find ties between the two suspects too.

He arranged for the Police Department to issue a “crime bulletin” to local media outlets describing Tatro as a “subject of interest” in homicides that occurred in the early to mid-1980s. It included a photo of him and a description of the blue-and-white van he drove. It didn’t mention that he was dead.

The bulletin, which generated a short story in the Union-Tribune, asked anyone who knew Tatro “or his associates” to call the cold case team. No valid tips came in.

Lambert also sent a confidential bulletin with two photos of Brown on it to law enforcement agencies nationwide. It identified him as a former criminalist whose hobbies included nude photography.

The bulletin said Brown was being investigated in connection with the murder of a teenage girl who had been raped, beaten, stabbed and strangled. It asked the agencies to review their unsolved homicide files “for any similar cases” and compare the evidence with Brown’s DNA.

Again: nothing.

Lambert interviewed people who knew Brown. He went to China Lake and met with Navy physicist Kevin Sheldon, a former roommate. He showed him a picture of Tatro; Sheldon didn’t recognize him.

Sheldon told the detective how meek and impressionable Brown was — that you could get him to do and say almost anything. But, Sheldon later recalled, that didn’t seem to be a message Lambert wanted to hear.

He quoted the detective as saying that Brown was playing “a cat and mouse game,” but that wouldn’t stop police from solving the case. To Sheldon, Lambert had already made up his mind.

The detective wasn’t the only one.

‘A weird vibe’

In the fall of 1992, 10 years after he had moved to San Diego and eight years after Claire Hough was murdered, Kevin Brown placed a personals ad in the Union-Tribune, “men seeking women.” It said he was interested in a slender nonsmoker for a possible relationship.

Rebecca Blakely saw the ad, called the phone number and left a message. On Dec. 4, 1992, they had their first date, at the Harbor House restaurant in Seaport Village. It went well.

They did a Venn diagram to chart their commonalities: dancing, cats, music. It turned out that each had the same car-radio stations programmed as presets.

“I thought he was really sweet,” Blakely recalled later. “He was quieter and thoughtful. He seemed very respectful. He was not loud. He was not demanding. He was not pushy. He was not arrogant. Things I did not want to get involved in.”

By the third date, to watch the Christmas boat parade, she knew she wanted to marry him. She asked if he would kiss her. He did.

The wedding was about eight months later, in Lake Tahoe. It was her third marriage, his second. Neither had children.

Her family was not thrilled with the relationship. Some of them found Brown reclusive and odd. “Look what the cat dragged in,” one relative whispered to another the first time they saw him. “I got a weird vibe,” said another.

Their suspicions bubbled up again when they learned he was being investigated in the Hough case. Rebecca Brown’s sister called and asked flat-out whether he had sex with the girl. He said “yes,” according to her account. She said she called Lambert and relayed the conversation.

Brown thought his comment was taken out of context. The phone conversation with the sister-in-law came shortly after the police interrogations. Detectives had led him to believe he’d had sex with Hough because that was the only explanation for his sperm winding up on the vaginal swabs.

He didn’t believe that for long.

He started thinking more about his time in the lab and talking to some of the criminalists he used to work with back in the 1980s, including James Stam, a former boss.

Stam believed contamination was the likely explanation for what happened. He remembered how different things were in the lab back then, in the days before DNA analysis. How criminalists all worked at large tables in the same cavernous room, not always wearing masks or gloves. How evidence swabs were left in the open air to dry.

And how they brought their own semen into the lab, kept it on small pieces of cloth to use in testing. The cloths were stored in desk drawers or the refrigerator, available for anyone to use.

“We weren’t being a willy-nilly, crummy lab,” Stam said. “It’s just the way things were.”

Stam was interviewed by Lambert and told him he didn’t think Brown was guilty. The detective begged to differ, pointing out incriminating statements Brown had made during the interrogations.

That information didn’t impress Stam. He remembered the problems Brown had as a criminalist testifying in court, how he could be pushed around by defense attorneys and talk himself into trouble.

“Until you can eliminate contamination,” Stam remembered telling the detective, “you can’t go anywhere further with this.”

To Lambert, it had already been eliminated. His boss told him that when he first got the case. So he saw no need to go into detail with Stam about the lab practices in 1984. He didn’t ask any of the other criminalists he interviewed, either.

That left him surprised by what came next.

A bullet on the floor

On Sept. 26, 2014, Lambert and his partner, Lori Adams, interviewed Steve Blakely, one of Rebecca Brown’s brothers. He told the detectives he could imagine Brown committing the murder “because there is something off about him.” His wife, Nancy, was so concerned about the allegations she barred Kevin Brown from their house and took his picture off a wall.

Steve Blakely also told detectives about comments made by the Browns several months earlier. The couple shared their belief that Kevin had been implicated in the Hough case through contamination, and that it occurred because he had his sperm in the lab.

“I thought there was no way that (sperm in the lab) could happen,” Steve Blakely told the detectives.

Lambert had the same reaction. “Like, eww, why would you do that?” he remembered thinking. “I never heard that before in almost 30 years of law enforcement.” It wasn’t something the Browns had ever shared with him, either.

After the meeting with the Blakelys, Lambert called the police lab and asked David Cornacchia, who had done the DNA work in the Hough case, whether criminalists kept their own semen in the lab.

It’s true, Cornacchia said. True in 1984, and true now.

Lambert’s stunned reaction caught the criminalist off-guard. “It is funny,” Cornacchia said later, “because at that moment I realized I have been doing this for so long, I didn’t realize that it (semen in the lab) is kind of weird.”

Stunned or not, Lambert didn’t alter his investigation because of the revelation. He said Cornacchia told him that lab managers were aware of the practice when they concluded that contamination was unlikely in the Hough case.

“He’s on the science side of things, and I have to trust in the fact that when he makes an identification in the lab, that they observed whatever protocols are pertinent to them,” Lambert would later say. “We don’t challenge them on their work and how they do it.”

Cornacchia, however, wasn’t in the lab in 1984 and didn’t know how it operated. He said he told Lambert that.

As all this was going on, Brown’s struggles continued. His weight loss was nearing 25 pounds on an already thin frame. He stopped gardening and doing other things he enjoyed. He had trouble concentrating and spent hours sitting in chairs, staring. His hands sometimes shook.

Rebecca Brown tried to pull him out of it. In late September, they scheduled a date night. She came home from work and found him in bed, lethargic.

There was a bullet on the floor and what she thought might be a suicide note. It thanked her for the 20 years they’d been married. “They’ve been wonderful,” he wrote. “You’ve been wonderful.”

He denied that he was thinking about killing himself, but his brother-in-law, John Blakely, was concerned enough to take three guns that were in the house and lock them away.

A defense attorney, Blakely had been giving Brown informal advice during the investigation, but he wasn’t representing him. In fact, he told Lambert he thought Brown might be guilty: “To me, he fits the profile of somebody who might be involved in something like this.” He also told the detective about the apparent suicide note and the guns.

A short time later, Lambert went to the school where Rebecca Brown worked. He said he wanted to make sure she was OK and not in any danger from her husband.

She told the detective that the only person Kevin Brown was likely to harm was himself.

It’s not coming back

October 2014. Lambert had been investigating Claire Hough’s murder for almost two years. He was getting close to presenting the case to the district attorney’s office for a decision about whether to charge Kevin Brown.

Out of the blue, Brown called and made another appointment to speak with the detective. He wanted to know when police would be returning the items they had taken nine months earlier during the search.

This, according to what Rebecca Brown remembered her husband telling her, was Lambert’s reply: You know you killed her. I know you killed her. And you’re not getting your stuff back until you confess.

“He was crestfallen,” Rebecca Brown said.

Lambert denied he would ever tell a suspect that — “I would be worried that they would flee” — but the result was the same: The stuff didn’t come back.

In mid-October, Rebecca Brown got a phone call from her sister, Pat Stengel, who lives in Missouri. She said she had just talked with Lambert, who told her his investigation was wrapping up.

“And then,” Stengel said, “it’s bye-bye Kevin.” Rebecca Brown shared that with her husband.

That weekend, Rebecca Brown was directing a play at the high school where she worked. Her husband would usually come along and video-record the performances. But she had told school officials about the ongoing murder investigation, and they banned him from campus.

He suggested going in disguise. She said no. He was downbeat the whole weekend, so out of it she took away the pills he was taking for anxiety and insomnia. He called Lambert and canceled the appointment they had for another interview.

The next day, Oct. 20, Rebecca Brown came home from work and her husband wasn’t there. He’d left about 10 a.m. to run some errands.

One of them was to Home Depot, to buy a rope.

One was to a cabin the family owns near Julian, to get a white plastic chair from the front porch.

Rebecca Brown reported him missing. The next day, rangers in Cuyamaca Rancho State Park spotted his black Ford Ranger parked off Highway 79. They walked down a dirt trail.

Kevin Brown was hanging from a tree, dead.

Editor’s note: This story was compiled from thousands of pages of police reports, court filings, sworn depositions and trial transcripts. Unless otherwise noted, the quotes used are from those records.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.