How we investigated the use of restraints on psychiatric patients

- Share via

Where did the data come from?

To report this story, The Times analyzed data collected by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, the federal agency that has gathered restraint information from psychiatric inpatient facilities nationwide since 2013 as part of its Inpatient Psychiatric Facility Quality Reporting Program.

The Times initially sought to include all available years of data in its analysis, but inconsistencies in federal data for Los Angeles General Medical Center in 2016 and 2017 made that impossible.

L.A. General’s inpatient psychiatric unit has restrained patients at a higher rate than in any other in California, a Times analysis has found.

In those years, federal data show the hospital had a volume of patients more than 20 times higher than other years in its psychiatric unit at the Augustus F. Hawkins Mental Health Center, resulting in a dramatically lower restraint rate.

CMS said agency officials believe L.A. General had submitted “incorrect data” during those years, when it was known as L.A. County-USC Medical Center. L.A. County, which runs the hospital, said that it turned in correct data and that CMS appeared to have posted incorrect figures on its site.

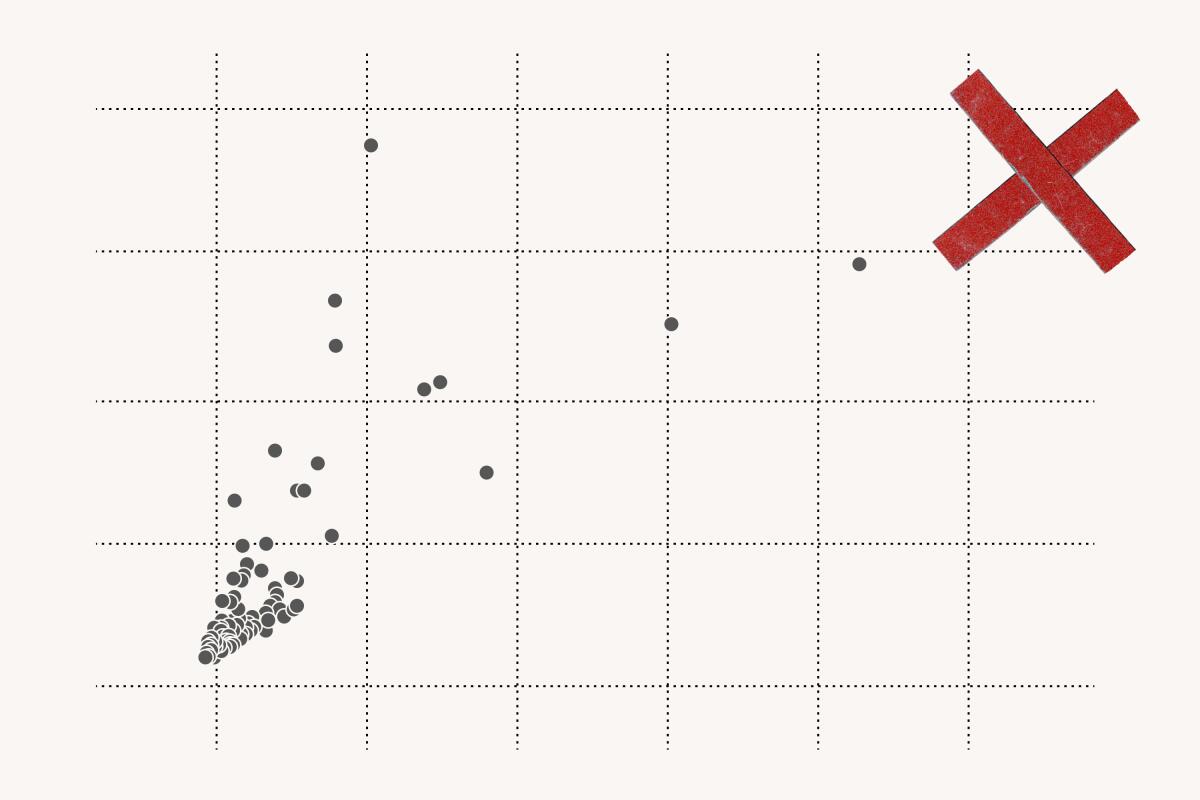

To avoid those years, The Times decided to analyze data about restraint use from 2018 to 2021, reflecting the most recent data available. The Times analysis found that during that time, the restraint rate at Hawkins ranked first in the state and in the top 10 for all inpatient facilities nationwide.

Reporters also wanted to determine how L.A. General’s inpatient psychiatric facility ranked among hospitals with the highest patient volumes in the country, since smaller hospitals can be more prone to dramatic changes in their restraint rates due to their small numbers of patients.

With guidance from healthcare data experts, the reporters identified large facilities as those in the 75th percentile for the total number of days patients stayed in each psychiatric facility. Among those high-volume hospitals, L.A. General ranked highest in the country for its restraint rate.

How did we figure out how long patients were restrained?

Through public records requests, The Times obtained reports that L.A. General submitted to the county’s Department of Mental Health showing the total number of hours that each psychiatric patient was restrained in a given month. The reports do not identify those patients.

The Times used those reports, many of which were handwritten, to build a database. Among the reports from 2018 through April, reporters found more than 200 cases in which patients had been restrained for a total of 24 hours or more within a month in L.A. General’s inpatient psychiatric unit.

High rates of restraining psychiatric inpatients do not automatically spur action by regulators, The Times found.

In addition, The Times reviewed medical records for two patients who were restrained not at Hawkins but on the main campus of L.A. General. Such episodes are not included in federal reporting of restraint hours. Reporters analyzed the medical records, which include doctors’ restraint orders, to assess how long the two patients were restrained during their hospital stays.

What are other factors that contribute to restraint?

The problem has alarmed hospital staff, who have ramped up security at Hawkins. Four years ago, state workplace safety regulators cited the hospital after two incidents in which a psychiatric inpatient at Hawkins injured staff.

After The Times asked for assault figures, the county health services department provided data indicating that the average number of attacks at Hawkins each month had not increased between mid-2018 and spring 2022.

The Times also obtained data from the California Department of Industrial Relations, which requires many hospitals to report information about serious episodes of workplace violence suffered by their staff. Those figures did not show an increase in the number of attacks on L.A. General personnel in all hospital units between 2018 and mid-2023.

Hospital and county officials attributed the high rate of restraints to an increase in patients with a history of violence. The county health services department initially said in a statement to The Times that L.A. General was the “primary recipient of dangerous incarcerated psychiatric patients who are released from custody and transferred to psychiatric facilities” under an L.A. County program that diverts people from jail into community-based housing and care.

But officials with that diversion program said clients released from jail under the program are sent to Olive View-UCLA Medical Center, not L.A. General. They also bristled at the suggestion that people diverted from the jails were dangerous, saying that they “have been deemed safe for release by the courts.”

If you want to learn more about how regularly a local hospital uses restraint on psychiatric patients, and how those restraint rates compare with state and national averages, here’s where to look.

The county department then said it had incorrectly referred to the diversion program rather than “in general to individuals released from jail,” and pointed to a list of changes to the criminal justice system over more than a decade that aimed to divert Californians from prisons and jails.

Experts and advocates interviewed by The Times said it was unclear that those changes could be connected to any shifts in the patient population at L.A. General.

“It is very difficult to credibly link the statewide criminal justice reforms to increases in patient violence at a particular hospital,” said Magnus Lofstrom, policy director of criminal justice at the Public Policy Institute of California, who has studied the effects of changes in the justice system. “There are so many potentially confounding factors that can drive these patterns — some local, some statewide, and some that are national.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.