- Share via

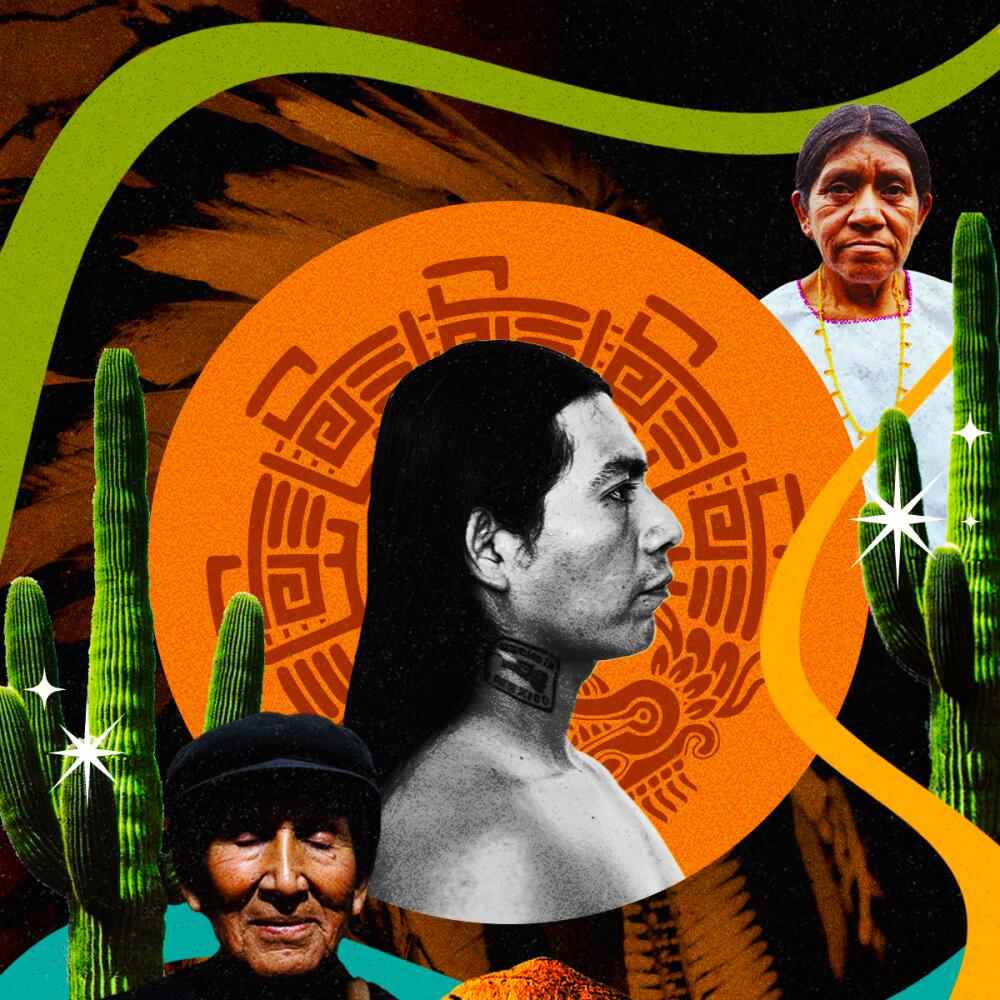

For many diasporic Latines, an inevitable argument arises around identity and language. If you don’t speak the primary language of your home country, whether that’s Spanish, French or Portuguese, the implication can be that you are not Latine or “Latino enough.” But this framing ignores the thousands of Indigenous languages still spoken by First Nations across Central and South America.

For speakers of some of the most commonly spoken native languages like Quechua, Nahuatl or Guarani, the conversation is less about whether you speak the language but rather how Indigenous languages are left out of the discussion.

“In school, they would ask: ‘What dialect [of Nahuatl] do you speak?’ as a way to devalue you,” said David Marcelino Cayetano, co-founder of Speak Nahuatl, an international online language school teaching the diaspora the Nahuatl language.

According to a recent analysis from Pew Research, 78% of U.S. Hispanics say it is not necessary to speak Spanish in order to be considered Hispanic. Within the group of Latinos who don’t speak Spanish, however, 54% say they have been shamed because of it.

Cayetano grew up in what is now known as San Luis Potisí, a Mexican state, with the Soquitipa community. Despite the region having a large Indigenous population, Cayetano recalled being discriminated against by non-Indigenous people, especially at school.

“If you spoke your [native] language [teachers] would punish you or they would look at you like, oh, he’s too ‘indio’ (native), and so they would impose who was more modern or who was more educated,” he said.

The discrimination Cayetano experienced extended beyond language, “It’s not just your language, it’s also your clothing and your way of life, like how your parents teach you to work with plants medicinally and teach you to work with the land. [Non-Indigenous] people will say no, that’s outdated, that’s too ancient,” Cayetano said, speaking in Spanish, his second language, but one he was forced to learn.

At his school, Speak Nahuatl, Cayetano not only teaches the language but also the deeper meaning behind the words. He says it’s not enough to just learn the words or the dialect.

“It’s not easy, this work,” he said. “At times, it makes one want to throw in the towel ... because it’s exhausting and it’s a heavy responsibility. Because you’re not just teaching someone in Nahuatl how to say, ‘My name is,’ you’re teaching them the deeper meaning and wisdom.”

Many of Cayetano’s students live outside Latin America and want to not only reclaim their Indigenous roots but also preserve the language.

Most also say it’s not necessary to speak Spanish to be considered Latino, the Pew Research Center analysis found.

“It’s been a lifelong journey,” said Cuitlahuac Areola Martinez, a teacher at Speak Nahuatl who began as a student. “Cuitlahuac is my real name, Cui for short, and so every single year [I’m] having to deal with, ‘Oh, wow, look at your name. I can’t pronounce it.’”

Martinez recalled being made fun of for his name when he was a child living in the U.S. after migrating from Mexico.

As he got older, he began researching his ancestry and roots and realized he felt separated from his Indigenous culture. Like many who have assimilated, he learned Spanish as his first language. In the U.S. he began going by “Chris” to avoid embarrassment.

In 2016, he began taking Nahuatl classes in the Huasteca dialect every Sunday La Plaza de Cultura de Artes in Los Angeles. That was where he met Cayetano, and after a while, Martinez became proficient enough to teach others the language.

“Sometimes it can be dark, because when you’re learning the language, you’re also learning the culture and traditions that were lost, but we are also reclaiming them,” Martinez said.

Reclaiming and preserving Latin American Indigenous language has gained popularity in the U.S. for several decades as more and more native languages have become extinct over time.

In 2016, the last female speaker of the Resígaro language — Rosa Andrade of the Ocaina tribe — was murdered in Peru, according to Survival International. Although the government assigned her to teach Ocaina to the community prior to her death, the language has since been considered one of the hundreds of extinct Indigenous languages in Latin America.

In a sweeping reversal, the Pulitzer Prize Board will accept submissions from non-U.S. citizens but the change will not go into effect until 2025.

In the Caribbean, academics thought the Taíno people were extinct for hundreds of years. They were the first Native people to come in contact with Columbus and the conquistadores. The Taíno language, which originates from the Arawakan dialects of the Amazon, was then considered extinct by default. However, DNA technology, archaeological evidence and cultural research have proved that not to be the case and Taínos simply assimilated into society while keeping much of the language and traditions alive.

“One part of my family comes from San Juan de la Maguana which is considered the Taíno capital of Quisqueya, of the Dominican Republic,” said Irka Mateo.

Mateo has been reclaiming Taíno spirituality for almost 40 years and teaches Taíno ritual workshops in Los Angeles and online.

“There are many, many, many traditions, spiritual beliefs there, that are still present today,” he said.

Despite the Caribbean, and in turn, the Taíno people, having been under Spanish occupation for hundreds of years, the language and customs survived due to preservation and now reclamation.

Although fluent Taíno speakers are difficult to find, those who are reclaiming the language don’t want that to be a barrier.

“For example, the word ‘baguada’ comes from ‘bagua,’ which means ocean [in Taíno],” Mateo said. “And when there is a storm that comes from the sea, we say, ‘Por ahi viene una baguada’ (here comes the storm).”

Along with reclaiming the Taíno language in the Hiwatahia dialect, her work focuses on preserving Taíno spiritual customs and practices.

Latinidad is an ever-expanding concept, but it has not often made space for the Garifuna people who come from various regions of Central America.

“It brings healing. It’s been beautiful learning my language” said Martinez, “noticing that these words, especially with food and animals and plants, are from our [town].”

The connection with native foods and plants helps those who are preserving their Indigenous language and keeps them grounded in their intentions to keep their dialects from becoming a thing of the past.

While Latine identity across the diaspora will continue to evolve and shift over time, those who are preserving and reclaiming Indigenous languages and dialects are hopeful they can contribute positively to the progression of a more decolonized identity for First Nations people and their descendants.

“I remember [teachers] would say, ‘The Aztecs and the Mexicas existed once and they spoke Nahuatl … ,’ and you think to yourself, ‘Wait, I have always spoken my native language,’” Cayetano said. “You’re in your own land, your own country, and they are educating you like you don’t exist.”

Constanza Eliana Chinea is a culture journalist, producer and social justice activist living in Los Angeles. She currently co-hosts and produces the video and audio podcast “Stranger Fruit,” a show tackling taboo topics with diverse cultural thinkers. @eliana.chinea

More to Read

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.