- Share via

MONTERREY, Mexico — When Yadira Ayala was a child, she walked along one of the many dirt paths on Cerro Loma Larga to her grandmother’s home. She lived on the hill next to Ayala’s house in Colonia Independencia, a working-class neighborhood in northern Mexico.

The industrial city of Monterrey sits at the foot of the vast mountain, and on the other side is San Pedro Garza García, one of the wealthiest municipalities in Latin America. With this privileged view, Ayala’s grandmother warned her as she gazed at the top of the hill: “Cuidado, here comes the rich.”

“I remember my grandmother saying, ‘Ay, mija, they want to remove us from here because they want to build elegant houses,’” Ayala, now 43, recalls.

Her abuelita’s premonition wasn’t too far off from what was to come.

In the last decade, the state government and developers have targeted the Loma Larga, a natural border between Monterrey and San Pedro, to build road links and luxury housing.

La Indepe, in part because of its geographic location, has been persecuted by various actors, from state builders and the church to organized crime and the government. However, beneath the stigma of poverty and violence imposed on La Indepe lies a network of neighborhood solidarity, a model of community life that is under constant threat, and mucha cumbia that keeps arriving from Colombia.

::

On a hot Sunday morning in September, a group of about twenty people gathered in front of the mercado Díaz Ordaz. They arrived for a special baile held in benefit of sonidero Tongo de Valleverde, who is in need of a prosthesis. A sonidero is a combination of a DJ and MC who plays various subgenres of cumbia, salsa and other regional genres.

An old-school sound system blasts porros, gaitas and cumbias colombianas, while residents sell secondhand clothes, tostadas and old records.

1

2

3

1. Attendees watch a dance with sonideros at the Diaz Ordaz market. (Velia de la Cruz / For De Los) 2. Jorge Solis Hernandez, owner of the Discos Viniles LP store inside the Diaz Ordaz Market. (Velia de la Cruz / For De Los) 3. A vendor at the market sells shirts and records. (Velia de la Cruz / For De Los)

José Vázquez takes an album from a box of vinyl records and puts it on the turntable. A tropical rhythm fills the atmosphere. Some of the men wearing colorful sombreros vueltiao move their hips from side to side as they drink beer under the Puente del Papa (named after the visit of Pope John Paul II to the city in 1979), which connects downtown Monterrey to La Indepe.

“La Colonia Independencia is the mother of all the neighborhoods in Monterrey,” Vázquez said.

1

2

3

4

1. Diaz Ordaz Market located in the Independencia neighborhood. (Velia de la Cruz / For De Los) 2. Raul Becerra of Sonido Rena y Hermanos plays vinyl during a dance event. (Velia de la Cruz / For De Los) 3. A couple dances during a sonideros event at the Diaz Ordaz Market. (Velia de la Cruz / For De Los) 4. Two couples dance during a sonideros event at the Diaz Ordaz Market. (Velia de la Cruz/For De Los)

La Indepe was originally called Barrio San Luisito because it was built by domestic rural migrants, mainly from the central state of San Luis Potosí, who came to build the foundations of the city. It is also known as La Colombia Chiquita because of its connection to the barrios in Colombia. The cumbia and vallenato that blare from the speakers in the barrios of Barranquilla or Medellín can also be heard in the streets of La Indepe.

“We even share the mountains with Colombia,” Vázquez said.

Many Salvadorans are raised to believe there are no Black Salvadorans. Afro Salvadorans still face stigma, and even erasure.

To outsiders, La Indepe is a settlement of colorful houses spread over several hills between the Río Santa Catarina, a mostly dry river that runs through the city, and the top of the Loma Larga. It is considered one of the most violent and dangerous neighborhoods in Monterrey. For residents, La Indepe has several barrios: Tanques de Guadalupe, America 2, Ciudad Perdida (La Cima), and dozens of others. They are neighborhoods built from the ground up by their own residents with a strong sense of community ownership.

Yasodari Sánchez, a researcher from La Indepe, has continued the tradition of the sonideros as a space to strengthen the community. Once a month, she tries to organize charity dances to support someone in the community. While people listen to the sounds of the various sonideros, Sánchez collects money in a water jug.

“It may be something exceptional in other places, but here sonideros have always been part of community building,” Sánchez said. “The sonideros have always been an axis in supporting health contingencies, but also in other actions such as when we discussed the tunnel project.”

Years ago, the government proposed a link between San Pedro and downtown Monterrey without consulting residents. United under the slogan “La Indepe is not for sale,” residents blocked main avenues and protested in front of the government palace. Ramiro Gámez of Sonido Gámez said that when they realized many residents would be evicted, the sonideros joined, bringing along their most precious compañera: la cumbia colombiana.

For speakers of some of the most commonly spoken native languages like Quechua, Nahuatl or Guarani, the conversation is less about whether you speak Spanish but rather how Indigenous languages are left out of the discussion.

“All of Monterrey knows that the Colonia Independencia is the cradle of the sonideros,” Medrano said. “So since the Independencia was protesting, we brought the sound system and the cumbia. This is our tradition.”

The project was stopped by a judicial action and a government environmental study that determined that the Cerro Loma Larga has areas of flora and fauna at risk. Ericka Charles, one of the organizers and spokesperson of the neighborhood council, said that in a place like La Indepe, coming together for a common cause was the natural thing to do since almost everyone knows one another.

“I believe that the most valuable thing here in this neighborhood is the unity that exists among the people,” Charles said. “There is a lot of cariño between people.”

::

On the San Pedro side, luxury residential towers and gated communities are moving closer to Ciudad Perdida, one of the neighborhoods at the top of the city’s hill. Once the roads leading to these complexes finish, the pavement ends and the dirt road begins. The water and power supply also end there.

The poor infrastructure in the higher elevated neighborhoods is mainly due to negligence, according to residents.

Laura Marín, who lives in one of the last houses on the hill, is surprised that the buildings she sees from her porch have these services.

“How do they have [these services] and we don’t? Every time we ask [authorities] to regularize our services, they tell us that we live too high up,” Marín said.

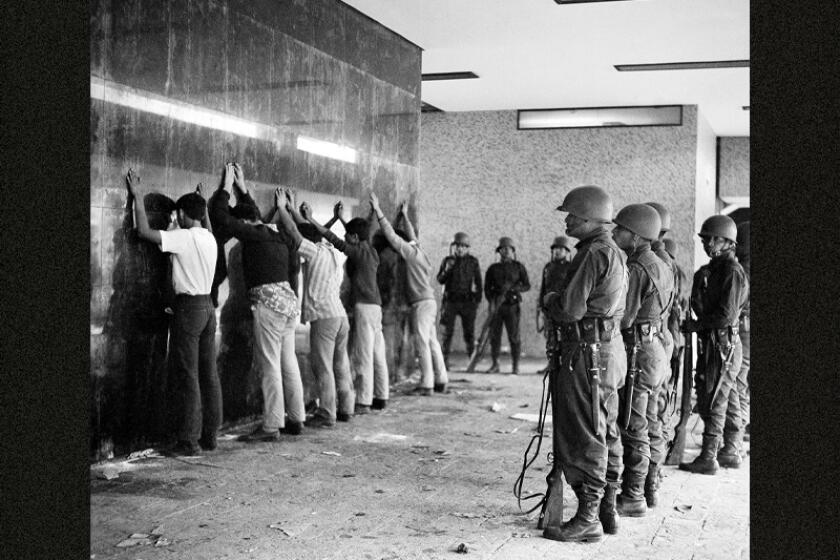

Fifty-five years ago, Mexico’s authoritarian government killed students during a peaceful demonstration. It would later become known as the Tlatelolco massacre.

However, the elevation of the neighborhood was not an obstacle when it came to erecting a sculpture of the Virgen de Guadalupe, 12 meters high and weighing four tons. This was the beginning of a religious tourism project, led by the Archdiocese of Monterrey and supported by the state government, that mobilized Marín at the risk of being displaced. Most of the houses in the community are considered irregular settlements, and most families do not have title deeds.

“The land belongs to those who work it,” said Marín, quoting Mexican revolutionary Emiliano Zapata. “We have been here for years since our families came.”

Marín contacted Charles to join the protests against the church project, but the community didn’t respond in the same way. La Indepe is home to the Basílica of the Virgen de Guadalupe, which every Dec. 12 receives thousands of parishioners who come to sing her the mañanitas. Marín joined a couple of protests but was afraid of becoming too visible.

“It wasn’t for me. I saw that in the newspaper they generalized a lot,” Marín said about the attention the protests were receiving. “I felt like they were trampling on one’s dignity.”

To get to Ciudad Perdida, visitors can walk up long staircases, or take a taxi — also called piratas — which travel through the narrow and steep streets. On the way up, at the various lookout points, there are young boys with walkie-talkies — called halcones — who have been recruited as organized crime spotters to warn of intruders.

Men in bulletproof vests roam the streets carrying military-grade weapons, while children play and residents make their way to the bus stop to get to work.

This led Marín to believe there was another way to connect with her community besides protests. Every Tuesday and Thursday afternoon, she hosts a small group of children, ages 6 to 13, to teach them music, arts and crafts, “or whatever they feel like doing.”

On a Tuesday in September, three girls and two boys sat on the porch of Marín’s house and traced animal drawings from an old coloring book.

In Jessie Fuentes’ hometown of Eagle Pass, he sees concertina wire and a floating barrier outfitted with serrated blades on the river where he grew up.

“I want to give all the options to the children so that they can see. And from now on they can start thinking: ‘I want to do this, I want to do that,’” Marín said.

For years, Marín made and sold cakes. In addition to cleaning houses, she dedicated herself to creating the best cake designs for birthdays, quinces and weddings. Together with her husband who works in construction, they have focused on giving their two daughters a college education.

::

With her grandmothers’ words echoing in her head, Ayala joined the art collective Desde el río hasta la loma, where her children participated in a workshop called “Lxs Niñxs de la Resistencia.” Created by local artists Julio Cisneros, Daniel Hernández and professor Luz Verónica Gallegos, this workshop teaches the richness of the hill’s habitat.

“The workshops were about feeling proud of the neighborhood, knowing that we have the right to be here, to stay here,” Hernández said.

Ayala, Hernández and other members of the collective organize cultural activities every month such as craft workshops and mural painting. Sometimes the community supports them with materials, or they organize dances to raise funds.

1

2

3

1. Libertad Chavez prepares glue that will be used in the design of the mural by the collective Desde el rio hasta la loma. (Velia de la Cruz / For De Los) 2. Daniel Hernandez participates in the creation of a mural in the Tanques de Guadalupe. (Velia de la Cruz / For De Los) 3. Mural made by the Desde el rio hasta la loma collective. (Velia de la Cruz / For De Los)

“It’s a constant struggle,” Ayala said. “But our idea is to transmit this to the new generation. That is the answer.”

From above, the Loma Larga looks like a safe haven. The presence of armed people in some parts is the loudest silence for residents, and a reminder that the so-called war on drugs has crept into the daily lives of the most impoverished. It’s also the only security in the neighborhood.

“The ones before were worse,” Marín said. “At least these ones don’t mess with us.”

Collective actions, Marín claims, have regained a greater voice. While some go to work or pick up the children from school, others wearily go up the hill, carrying market bags or materials for the next kids’ workshop.

Some people rest outside the corner store and drink a Coca-Cola or a caguama with the panoramic view spread out before them. The cumbia, like an anthem that renews, starts to play. Tomorrow they will go back down to the city and do the same thing again.

Chantal Flores is an independent journalist based in Monterrey, Mexico. She covers the issue of enforced disappearance in Latin America and the Balkans, as well as gender, violence and social justice.

More to Read

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.