In the U.S., geography is fate. A new book on poverty seeks to change that

- Share via

On the Shelf

The Injustice of Place: Uncovering the Legacy of Poverty in America

By Kathryn J. Edin, H. Luke Shaefer and Timonthy J. Nelson

Mariner: 352 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

“Where you live should not decide/ Whether you live or whether you die.” In U2’s “Crumbs From Your Table,” Bono castigates the wealthy West, especially the U.S., for its miserly and neglectful treatment of African countries long harmed by colonization.

A new book, “The Injustice of Place,” argues that America has been as bad, or worse, about perpetuating geographic inequality at home. U2’s lyrics resonate with the book’s depiction of “internal colonies” that perpetuate economic and social injustices against Black and Latino residents throughout the rural South as well as poor whites in Appalachia.

The authors posit that much of this nation has been built on a never-ending cycle of extraction and exploitation. And the book lays bare the truth about the unfairness of unregulated capitalism, says Timothy J. Nelson, director of undergraduate studies in sociology at Princeton. He co-wrote the book with Kathryn J. Edin, a professor of sociology and public affairs at Princeton, and H. Luke Shaefer, a public policy professor at the University of Michigan, where he directs Poverty Solutions. For their collaboration, the authors, who spoke by video in a joint interview, drove around the country visiting places left behind.

Matthew Desmond’s ‘Evicted’ changed the conversation about housing insecurity. He explains why his new book, ‘Poverty, by America,’ is even more ambitious.

“There has been a pillage-and-burn approach, and the government just turned a blind eye to this for generations if not centuries,” Edin says. “... These places have no middle class — there are haves and have-nots and nothing in the middle.”

The trio created an Index of Deep Disadvantage, measuring not just income and wealth but other markers including health and education. Perhaps not surprisingly, a map of those suffering the most largely overlaps with a map of the Confederacy (plus Native American reservations in the North and West). It’s another marker of white supremacist attitudes as the driver for much of the suffering in Black and Brown communities. (Sixty percent of African Americans live in the South again, and 40% of Latinos live in border states.)

And rural areas suffered the most, lacking the resources — public libraries, mass transit, accessible healthcare — that even the poorest, most segregated neighborhoods in large cities afforded their residents.

The co-authors chose communities to study in Appalachia, South Texas and the southern Cotton Belt that were representative from the bottom 200 of their list. The book presents a mix of qualitative and quantitative data, from statistics to interviews out in the field. According to Edin, their researchers had to spend months volunteering at soup kitchens or historical societies and going to community events before people would open up to them.

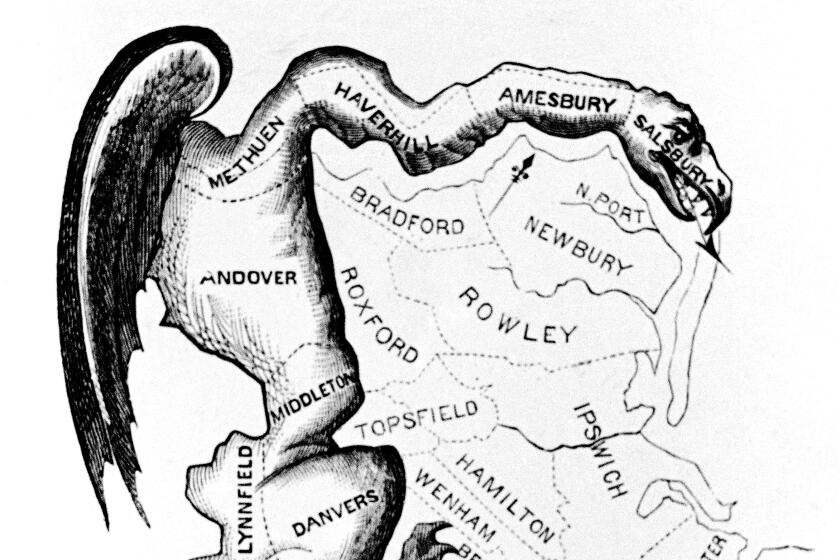

Nick Seabrook explains his new history, “One Person, One Vote,” and the way gerrymandering stymies everything from gun reform to democracy itself.

When the pandemic shut down field research, the trio filled their homes with manuscripts, dissertations and primary sources, studying the history of these communities, which deepened their understanding of the problems so present today. “It was a life-changing experience,” Edin says.

The authors know some readers may have a knee-jerk reaction to polarizing terms — structural racism, white supremacy — so they focus on the details of unfairness in America.

“When it comes to understanding structural racism, I hope one of our contributions is to show the nuts and bolts of how it works,” Shaefer explains. “In South Texas, they purposely held elections when migrant workers were out of town so they couldn’t vote. Is that fair?”

He also points out how Southern whites created “segregation academies” in the wake of “Brown vs. the Board of Education,” and how racist Citizens’ Councils arranged for these private schools to get preferential tax treatment that continues today. Meanwhile, when Black students do get to attend desegregated schools, their grades demonstrably improve (thanks partly to better resources). When hurricanes hit, Black communities end up poorer while white communities end up more affluent because longstanding property ownership laws impact government aid. “By pointing to these specifics,” Shaefer says, “we can make for a different conversation.”

Pouring money into these communities is tricky, Edin, says, because of the “extreme risk of elite capture,” where the wealthy — who, the book argues, view themselves as morally superior — siphon off grant money for local projects. “We need to rethink the way we give money away.”

The third installment of the United We Read series explores stories from Maryland to Oklahoma in advance of the 2020 election.

When I ask about universal basic income as one possible shift, Shaefer says he’s glad that conversation is progressing but there are still many details to work out. He and Edin previously wrote “$2.00 a Day: Living on Almost Nothing in America,” which helped lay the groundwork for the expanded child tax credit President Biden pushed into effect in 2021.

That credit directly and significantly lowered the poverty rate for children, especially Black and brown children, but Congress refused to renew it. Shaefer says making it permanent would be the simplest way to create dramatic positive change.

“We want to get money to families directly but also to target the systems themselves,” he says; one way to accomplish the latter would be increasing pay for new teachers in these communities. While Republican governors and state legislatures are unlikely to tackle that, he adds, “it’s pretty straightforward for the federal government to say, ‘We’ll boost the pay for new teachers in districts with poverty rates above X percent.’”

While these ills are deeply entrenched, Shaefer sees hope for improvement because some major problems — social isolation, political corruption — are not partisan. “These are issues that can appeal to a broad base of people, and you can bring people together and increase trust.”

There is a limit, however, to what the federal government can do. “Biden did increase federal spending on libraries but it’s a drop in the bucket,” says Edin.

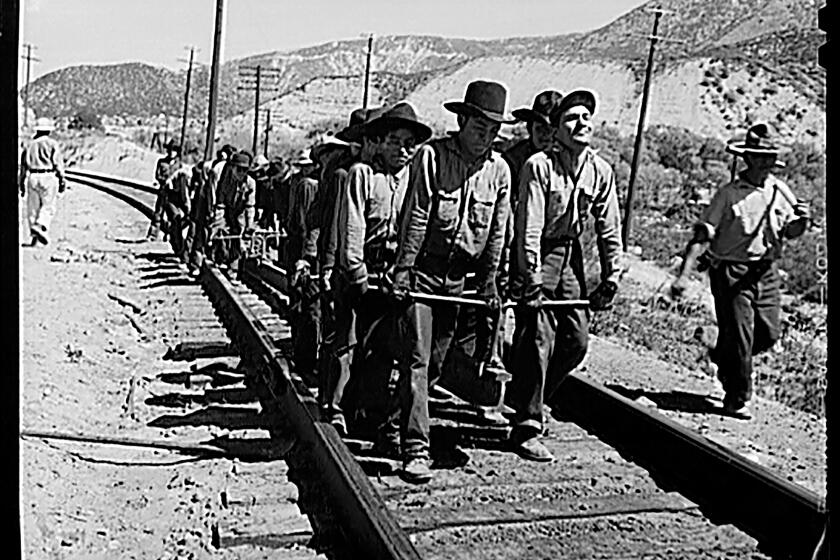

Jean Pfaelzer discusses recasting history in ‘California, a Slave State,’ which tracks the record of racism and forced labor that drove the state’s ‘startup’ culture.

Ultimately, they see a major opportunity for what Edin calls “focused philanthropy” to re-establish downtowns and social infrastructure, funding community centers, playgrounds, outdoor recreation programs, even local arcades and movie theaters — places where a community can come together and connect. “This is a perfect time for philanthropy to partner with local organizations and government,” she says.

Ferreting out local corruption — witness the massive Mississippi scandal in which former quarterback Brett Favre and others pocketed welfare money — requires a strong local press. Now that much of it has been decimated by the internet, Edin says journalistic nonprofits were essential to their research “and we need to add that to our arsenal of thinking.”

Edin says major change like school desegregation requires “a relentless march and is more of a long-term target,” but that shining the spotlight on the ways the government is failing its people often prompts change.

Additionally, Nelson says, public policy programs like the ones where they teach should take responsibility. “We train people to fulfill jobs at the federal level but not a lot at the state and local level of government, so that’s somewhere we can really step up.”

Local is key; just as poverty and need are geographically segregated, so should solutions be geographically targeted. But first and foremost, attention must be paid. Edin calls the book an “urgent clarion call” to break with the past. “Change is possible at the community level and national level,” Shaefer adds, “and we have to do both.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.