How to watch every best picture winner from 1990 through 1999

- Share via

The trend of best picture and best director Oscars going to the same films continued in the 1990s, starting with actor-turned-director Kevin Costner (“Dances With Wolves,” 1990); Jonathan Demme (“The Silence of the Lambs,” 1991); Clint Eastwood (“Unforgiven,” 1992); Steven Spielberg (“Schindler’s List,” 1993); Robert Zemeckis (“Forrest Gump,” 1994); Mel Gibson (“Braveheart,” 1995); Anthony Minghella (“The English Patient,” 1996); James Cameron (“Titanic,” 1997) and Sam Mendes (“American Beauty,” 1999).

All were first-time Oscar winners, and Costner, Eastwood, Spielberg and Gibson had numerous box office hits in their résumés. Spielberg picked up his second directing Oscar in 1998 for “Saving Private Ryan.”

How to watch Oscar best picture winners through the decades

Intro and 1920s | 1930s | 1940s | 1950s | 1960s | 1970s | 1980s | 1990s | 2000s | 2010s | 2020s (and 2020 nominees)

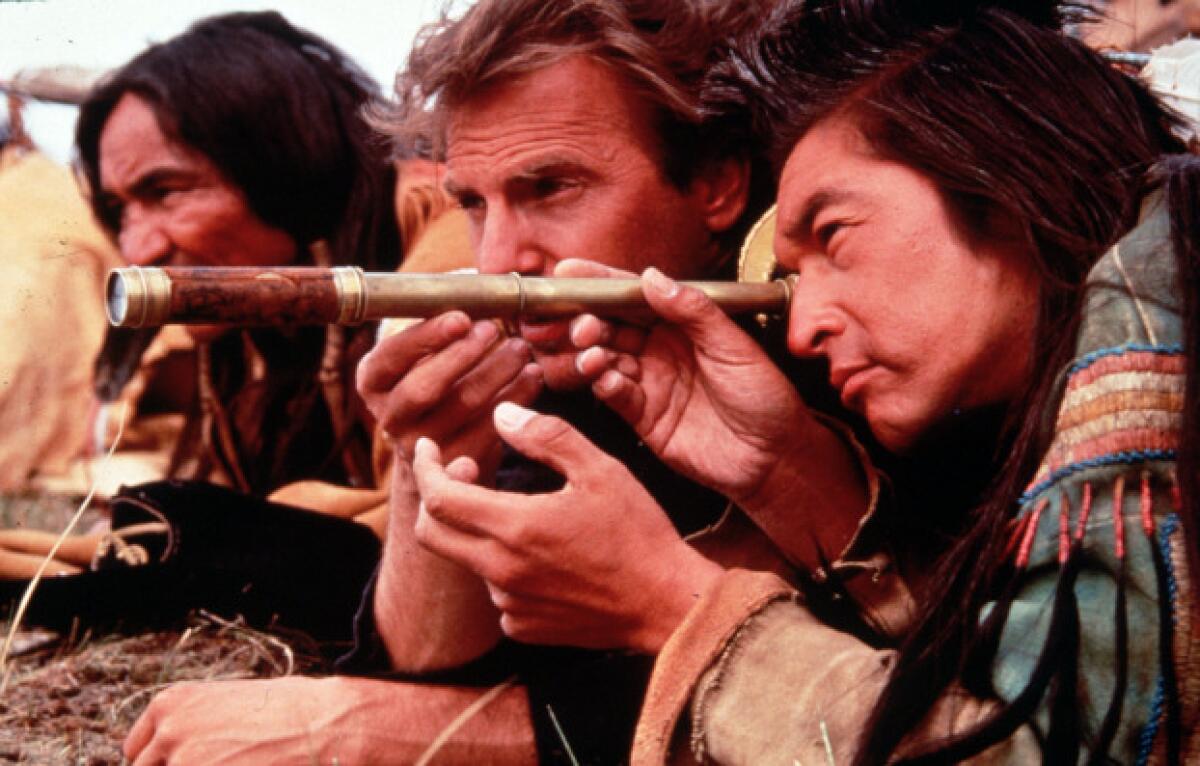

1990: ‘Dances With Wolves’

63rd Academy Awards — March 1991

Rating: PG-13.

Running time: 3 hours, 1 minute.

Streaming: HBO Max: Rent/Buy Prime Video: Rent/Buy | Apple TV+: Buy/Rent

Kevin Costner opens his stirringly fine “Dances With Wolves” by pitching us without prologue or apology into the thick of character and action.

Costner’s Lt. John Dunbar, a wounded Union officer, is next in line to have his foot sawed off at a Tennessee field hospital; preferring to die intact rather than mutilated, he steals back to his men. Nearly hallucinating, he chooses death by galloping between the stalemated Union and Confederate troops, drawing rebel fire and ending his pain.

During his final, full-tilt charge, muttering, “Father, forgive me,” Dunbar drops his reins and throws his arms up and out, looking like a circus rider or a Christ figure, or both. It’s a marvelous moment of cinema, but a dangerously risky one when the star is also the director, and a first-time director at that. It practically invites the professionally cool in the audience to drawl, “Well, who does he think he is?”

Quite clearly, Costner knows exactly who he is, what he is doing, and how to do it.

“Dances With Wolves” is a clear-eyed vision. Authentic as an Edward Curtis photograph, lyrical as a George Catlin oil or a Karl Bodmer landscape, this is a film with a pure ring to it. It’s impossible to call it anything but epic. (Read more) —Sheila Benson

Doris Leader Charge earned more money working for Kevin Costner for six months than she does in a year teaching Lakota, a Sioux dialect, on the Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota.

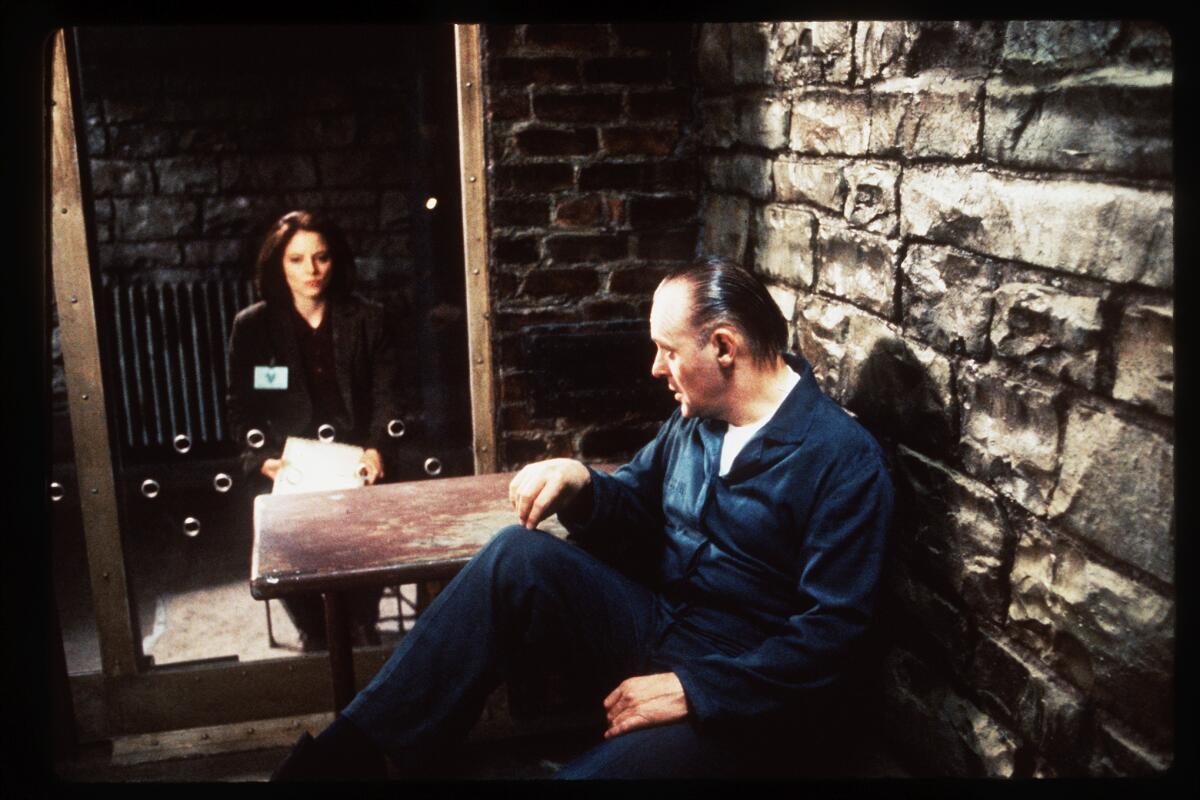

1991: ‘The Silence of the Lambs’

64th Academy Awards — March 1992

Rating: R.

Running time: 1 hour, 58 minutes.

Streaming: Prime Video: Rent/Buy | Apple TV+: Rent/Buy

The Jonathan Demme of “Something Wild” or “Melvin and Howard’ or “Stop Making Sense” might not be the first director one would think of for suspense or bloody terror; his touch has always seemed lighter, his interests more quirky and off the mainstream. So much for pigeonholing. Demme’s vision of “The Silence of the Lambs,” Thomas Harris’ truly terrifying novel, is stunning. It is also unusual — as the FBI races to save a kidnapped young woman from a serial killer, Demme concentrates on the hypnotic duel between his two strong central characters, an FBI trainee and a brilliant sociopath, rather than on easy effects calculated to make an audience jump.

They may jump anyway, since “The Silence of the Lambs” is marked by the second appearance of Dr. Hannibal Lecter — Hannibal the Cannibal — and Anthony Hopkins’ insinuating performance puts him right up there with the screen’s great bogymen.

Here in Ted Tally’s screenplay he very nearly owns the film. Only nearly — he would have to be superhuman to wrest this film away from Jodie Foster, and Lecter is only super-deviant.

Foster’s Clarice Starling is a promising FBI trainee in her last year, brought in by Jack Crawford (Scott Glenn), chief of the Bureau’s Behavioral Science Section, to do a psychological profile of Lecter. (Read more) —Sheila Benson

Here are the nominees for the 2023 Academy Awards in all categories, announced live Tuesday from the Samuel Goldwyn Theatre in Beverly Hills.

1992: ’Unforgiven’

65th Academy Awards — March 1993

Rating: R, for language, violence and for a scene of sexuality.

Running time: 2 hours, 11 minutes.

Streaming: HBO Max: Included | Prime Video: Rent/Buy | Apple TV+: Rent/Buy

The western is back. With a vengeance. Saddle up or get out of the way.

“Unforgiven” is not just any western either. Simultaneously heroic and nihilistic, reeking of myth but modern as they come, it is a western for those who know and cherish the form, a film that resonates with the spirit of films past while staking out a territory quite its own.

Produced, directed by and starring Clint Eastwood, “Unforgiven” is hard to imagine in anyone else’s hands. No other active player has made as many westerns, no one else has the connection with and feeling for the genre that only working in it for more than 30 years can provide. And starting as far back as Sergio Leone’s “A Fistful of Dollars,” Eastwood has delighted in bending boundaries, in pushing the western to areas outside the accepted canon.

So it’s not surprising that the producer-director in Eastwood recognized the strengths of David Webb Peoples’ exceptional screenplay, the unexpected turns its plot takes, the power of its idiosyncratic characters, the adroit way it mixes modern and traditional elements. More than that, Eastwood the actor was shrewd enough to hold onto the script for more than a decade until, just past his 60th birthday, he felt he had aged enough to do the role properly.

For “Unforgiven,” the story of a reformed killer who re-confronts his past, is very definitely an old-guy western, as elegiac in its own way as such classics as “The Wild Bunch” and “Ride the High Country.” As “True Grit” was for John Wayne, this is also something of a last hurrah for Eastwood’s “man-with-no-name” persona, but because Eastwood is who he is, it is a dark and ominous goodbye, brooding and stormy. (Read more) —Kenneth Turan

1993: ’Schindler’s List’

66th Academy Awards — April 1994

Rating: R, for language, some sexuality and actuality violence.

Running time: 3 hours, 15 minutes.

Streaming: Peacock: Included | Prime Video: Rent/Buy | Apple TV+: Rent/Buy

The more we know about the Holocaust, the more unknowable it seems to become. Like the mythological fruit of Tantalus, always just out of reach, its essence eludes us, too awful to fully comprehend no matter how passionately we seek to know and understand it.

One thing that does become clear, however, is that to approach the Holocaust from a dramatic point of view, detachment and self-control almost to the point of coldness are essential. The most memorable films about the period, from Alain Resnais’ 30-minute “Night and Fog” to Claude Lanzmann’s nine-hour-plus “Shoah,” share this reserve with such memoirs as Primo Levi’s “Survival in Auschwitz.” Only through the lens of restraint can those days be effectively seen, as Steven Spielberg, of all people, persuasively demonstrates with the quietly devastating “Schindler’s List.”

“Schindler’s List,” based on Thomas Keneally’s remarkable retelling of a true story, is itself a different kind of Holocaust narrative. For if the pressure of overwhelming death and even the release of miraculous rescue have become standard fare, the dramatic, contradictory personality of Oskar Schindler has never ceased to baffle and astonish observers from his time to ours. (Read more) —Kenneth Turan

“Schindler’s List” won seven Academy Awards, including best picture and director, and turned Steven Spielberg from a popular filmmaker (whose “Jurassic Park” was released the same year) into a more serious one.

1994: ’Forrest Gump’

67th Academy Awards — March 1995

Rating: PG-13, for drug content, some sensuality and war violence.

Running time: 2 hours, 22 minutes.

Streaming: Netflix: Included | Prime Video: Rent/Buy | Apple TV+: Rent/Buy

Forrest Gump may have an IQ of 75, but don’t be telling him he’s slow. “What does normal mean anyway?” his mama always used to say, among other things. “Stupid is as stupid does.” A kind of holy fool who succeeds brilliantly in life while nominally wiser folk get all bollixed up, Forrest’s story offers a bemused chance to view the most turbulent decades of recent American history through a particularly harebrained lens.

There is magic in “Forrest Gump,” but almost by definition magic can’t last and it doesn’t here. In many ways a sweet piece of work with a gentle and eccentric sensibility, this Robert Zemeckis-directed film stumbles whenever it attempts what Forrest never did — forcing its charm in search of obvious sentimentality and grander points about society. Forrest would have been horrified, and, as usual, he would have been right.

Convincingly played by Tom Hanks, Gump comes into view at his ease on a bus bench in Savannah, Ga., in 1981, talking away to whoever’s handy, oblivious as usual to the fact that some people are not in a mood to listen. His deliberate but charming Southern-accented voice-over (scripted by Eric Roth from a novel by Winston Groom) runs throughout the entire film, telling his story and, not quite coincidentally, the story of America from the 1950s through the 1980s. (Read more) —Kenneth Turan

In 1994, moviegoers flocked to “The Flintstones” and “Maverick” in May, and “Speed” and “The Lion King” in June.

1995: ’Braveheart’

68th Academy Awards — March 1996

Rating: R, for brutal medieval warfare.

Times guidelines: It includes lots of graphic warfare not for the squeamish.

Running time: 2 hours, 57 minutes.

Streaming: Prime Video: Rent/Buy | Apple TV+: Rent/Buy

In “Braveheart,” Mel Gibson plays 13th century Scottish freedom fighter William Wallace, and, boy, is his heart ever brave. So are his eyes, his mane, his pecs, his knuckles. But he’s not just brave — he’s smart too. As the young William’s father tells the boy just before the British slaughter him, “It’s our wits that make us men.”

At close to three hours, “Braveheart” is a great big chunk of brogues and pillaging and whooping. Gibson, who also directed, is priming us for an epic experience — “Spartacus” in kilts. As a filmmaker, he lacks the epic gift, but the movie, scripted by Randall (no relation) Wallace, works on a fairly basic level as a hiss-the-English medieval western. Gibson’s calisthenic efforts are clunky but they’re not boring, at least not until the film moves into battle overkill in the third hour and the soundtrack turns into one big aaarrgh.

Wallace, who leads a rebellion against the tyrannical English King Edward the Longshanks (Patrick McGoohan) after his wife (Catherine McCormack) is tragically sundered, is a celebrated Scottish hero about whom very little that isn’t legendary is known.

Gibson plunges straight into the folklore. Just before the Battle of Stirling, where his men are hopelessly outnumbered against the British, Wallace rouses his troops with a speech that plays like a Classics Illustrated version of the St. Crispin’s Day speech from Shakespeare’s “Henry V.” (Read more) —Peter Rainer

1996: ’The English Patient’

69th Academy Awards — March 1997

Rating: R, for sexuality, some violence and language.

Times guidelines: several scenes of notable sensuality.

Running time: 2 hours, 42 minutes.

Streaming: HBO Max: Included | Prime Video: Rent/Buy | Apple TV+: Rent/Buy

Love in the extremes of wartime. Love in a dangerous, unstable universe where questions of nationality and betrayal predominate. Love that sears and scars, like the pitiless expanses of the Sahara. Love that heals, like the verdant countryside of Italy. “The English Patient” explores it all, surely, grandly, operatically.

A mesmerizing romantic epic taken from Michael Ondaatje’s Booker Prize-winning novel, “The English Patient” stars Ralph Fiennes, Juliette Binoche and a radiant Kristin Scott Thomas in a story that spans two continents and a single world war. “The heart is an organ of fire” is its theorem, and it’s proved with absolute assurance.

Created by writer-director Anthony Minghella, the film echoes the Ondaatje book by being poetic at the core. While it inevitably picks and chooses among the novel’s plot elements, “The English Patient” retains the original’s elusive, evanescent soul.

It does so especially in the way it reveals itself. Nothing is straightforward, no story moves purposefully from Point A to B. Delicately calibrated between the present of Italy in 1944 and the past of North Africa in the late 1930s, the film’s John Seale-photographed images create a nonlinear dream-time sensibility, mysterious, exotic, not quite of this world. (Read more) —Kenneth Turan

1997: ’Titanic’

70th Academy Awards — March 1998

Rating: PG-13, for disaster-related peril and violence, nudity, sensuality and brief language.

Times guidelines: Too intense for small children.

Running time: 3 hours, 14 minutes.

Streaming: Netflix: Included | Paramount: Included | Prime Video: Rent/Buy | Apple TV+: Rent/Buy

To the question of the day — what does $200 million buy? — the 3-hour-and-14-minute “Titanic” unhesitatingly answers: not enough.

Note that despite the hopes of skeptics, aghast at the largest film budget of modern times, money enough to run a full-dress presidential campaign or put a serious dent in illiteracy, the answer is not nothing. When you are willing to build a 775-foot, 90% scale model of the doomed ship and sink it in a 17-million-gallon tank specially constructed for the purpose, you are going to get a heck of a lot of production value for your money. Especially if your name is James Cameron.

More than that, at “Titanic’s” two-hour mark, when most films have sense enough to be winding down, this behemoth does stir to a kind of life. With writer-director Cameron, a virtuoso at large-scale action-adventure extravaganzas, serving as ringmaster, the detailing of the ship’s agonies (compressed here from a real-life two hours and 40 minutes to a bit more than an hour) compels our interest absolutely.

But Cameron, there can be no doubt, is after more than oohs and aahs. He’s already made “The Terminator” and “Terminator 2”; with “Titanic” he has his eye on “Doctor Zhivago” / “Lawrence of Arabia” territory. But while his intentions are clear, Cameron lacks the skills necessary to pull off his coup. Just as the hubris of headstrong shipbuilders who insisted that the Titanic was unsinkable led to an unparalleled maritime disaster, so Cameron’s overweening pride has come unnecessarily close to capsizing this project.

For seeing “Titanic” almost makes you weep in frustration. Not because of the excessive budget, not even because it recalls the unnecessary loss of life in the real 1912 catastrophe, which saw more than 1,500 of the 2,200-plus passengers dying when an iceberg sliced the ship open like a can opener. What really brings on the tears is Cameron’s insistence that writing this kind of movie is within his abilities. Not only isn’t it, it isn’t even close. (Read more) —Kenneth Turan

Why are we still so fascinated with the Titanic?

1998: ’Shakespeare in Love’

71st Academy Awards — March 1999

Rating: R, for sexuality.

Times guidelines: Genteel nude love scenes.

Running time: 2 hours, 2 minutes.

Streaming: Hulu: Included | Prime Video: Included | Apple TV+: Rent/Buy

As the title more than hints, “Shakespeare in Love” is a romance (and one played by the irresistible pairing of Gwyneth Paltrow and Joseph Fiennes), but that is not the limit of its attractions. Part knockabout farce, part witty amusement, “Shakespeare” has the drollness we associate with playwright (and co-writer) Tom Stoppard, but it has the rare ability to wear its cleverness with grace and ease.

The idea is shrewder than merely transporting us back to London in 1593, just in time to see young Will Shakespeare (Fiennes) fall in love with Viola de Lesseps (Paltrow), the woman who is to become his “heroine for all time,” though that is certainly pleasant.

The trick is rather that we see Will’s relationship with Viola have a transforming effect on the play he’s writing, tentatively titled “Romeo and Ethel, the Pirate’s Daughter.” As this duo live through the real-life passions and tragedies of a widescreen romance, that play in rehearsal gradually but inevitably becomes (of course) “Romeo and Juliet.” (Those hoping for “Titus Andronicus” might want to stay home.) (Read more) —Kenneth Turan

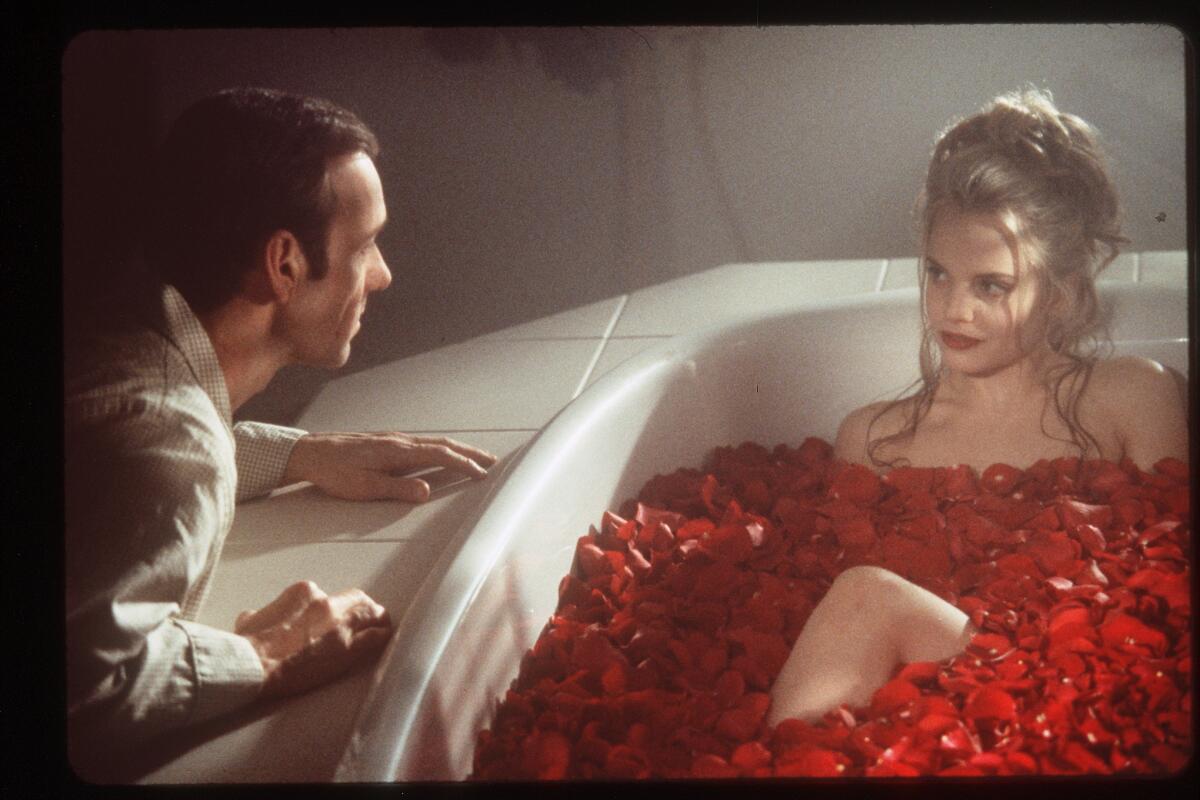

1999: ’American Beauty’

72nd Academy Awards — March 2000

Rating: R, for strong sexuality, language, violence and drug content.

Times guidelines: Some brief nudity, one scene of bloody violence, adult subject matter and considerable talk about sex. May be too disturbing for young teens.

Running time: 1 hour, 58 minutes.

Streaming: Prime Video: Rent/Buy| Apple TV+: Rent/Buy

Unsettling, unnerving, undefinable, “American Beauty” avoids quick and easy categorization. A quirky and disturbing take on modern American life energized by bravura performances from Kevin Spacey and Annette Bening, “Beauty” is a blood-chilling dark comedy with unexpected moments of both fury and warmth, a strange, brooding and very accomplished film that sets us back on our heels from its opening frames.

“This is my neighborhood, this is my street, this is my life,” Lester Burnham (Spacey) says in neutral voice-over as the camera narrows in from an aerial perspective to his red suburban front door as he delivers shock No. 1: “I’m 42 years old. In less than a year, I’ll be dead. Of course, I don’t know that yet. In a way, I’m dead already.”

To inform us that, as in “Sunset Boulevard,” we’re watching a film narrated by a corpse is a quick way to get everyone’s attention, but “Beauty,” the provocative debut for director Sam Mendes, goes further. Layered with surprises, at home in unfamiliar territory, this film more than doesn’t let on what it’s thinking or where it’s going; it intentionally misleads with dramatic dodges and feints calculated to throw everyone off balance and keep them there. (Read more) —Kenneth Turan

How to watch Oscar best picture winners through the decades

Intro and 1920s | 1930s | 1940s | 1950s | 1960s | 1970s | 1980s | 1990s | 2000s | 2010s | 2020s (and 2020 nominees)

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.