How to watch every best picture winner from 1950 through 1959

- Share via

In the 1950s, the movie industry was in transition. Following the Great Depression and Second World War, television was becoming a formidable competitor to moviegoing.

Partially in response to that competition, Hollywood studios invested heavily in widescreen technologies, and from 1955 on, best picture winners feature some sort of widescreen format, most notably the spectacles “Around the World in 80 Days” (1956), “The Bridge on the River Kwai” (1957) and “Ben-Hur” (1959).

The widescreen streak was broken with “The Artist” (2011).

How to watch Oscar Best Picture winners through the decades

Intro and 1920s | 1930s | 1940s | 1950s | 1960s | 1970s | 1980s | 1990s | 2000s | 2010s | 2020s (and 2020 nominees)

1950: ‘All About Eve’

23rd Academy Awards — March 1951

Running time: 2 hours, 18 minutes.

Streaming: Prime Video: Rent/Buy | Apple TV+: Rent/Buy

“All About Eve” is one of the smartest pictures of all time. It is about show people, and is preeminently for those who know about show-world people.

That does not mean its audience will be restricted, after all, a lot of people in America have charmed illusion about the men and women of the make-believe, whether it be in New York or Hollywood, and “All About Eve” shears these off with a vengeance. It is the very essence of backstage falderal bitterness and intrigue, and discloses with what foul scheming certain people will proceed to achieve their hour of triumph.

Joseph L. Mankiewicz, who wrote and directed “All About Eve,” elected Anne Baxter to demonstrate how far such scheming may go.

Bette Davis furnishes a sensational caricature. It is less than her greatest performances because it is a caricature, but it is also tremendously interesting on that account. (Read more) —Edwin Schallert

1951: ‘An American in Paris’

24th Academy Awards — March 1952

Running time: 1 hour, 53 minutes.

Streaming: Prime Video: Included | Apple TV+: Rent/Buy

Parisian glamour, albeit studio synthetic, glows resplendently from the screen in “An American in Paris,” which assures enjoyment for the public as few pictures have done thus far this season. It is original, gay and different; it has plenty of entertainment.

It climaxes in a radiant artistic carnival that is indeed unique. It is, in a word, an accomplishment to satisfy practically all beholders, and especially those who consider a splendiferous film musical one of the best reasons for attending a theater.

Gene Kelly stars in this picture — in fact, dominates it. Simultaneously the production introduces Leslie Caron as a singularly talented ballerina, and presents Oscar Levant and Georges Guetary in outstanding musical roles. (Read more) —Edwin Schallert

1952: ‘The Greatest Show on Earth’

25th Academy Awards — March 1953

Running time: 2 hours, 32 minutes.

Streaming: Prime Video: Rent/Buy | Apple TV+: Rent/Buy

The old trite phrase “with full panoply of glory” may well be applied to the way in which Cecil B. DeMille brings the circus to the screen in “The Greatest Show on Earth,” a picture to be reckoned as one of the greatest of this master showman’s shows.

DeMille provides the maximum of entertainment in his production, not to speak of glamour, and above all the spirit that forever lurks under the big top. DeMille himself is the narrator of the picture behind the scenes. His booming voice launches the film on the way with a vivid word impression of what the circus means.

Shining lustrously in the action is Betty Hutton as a trapeze artist, who finds herself in competition with Cornel Wilde in his spectacular role as a performer of the same type. Coolly devoted to Betty and ever authoritative in the circus is Charlton Heston, whose stock soars more than measurably because of his portrayal. James Stewart is concealed behind clown makeup but conveys a peculiarly sensitive interpretation of a fugitive. (Read more) —Edwin Schallert

1953: ‘From Here to Eternity’

26th Academy Awards — March 1954

Running time: 1 hour, 58 minutes.

Streaming: Prime Video: Rent/Buy | Apple TV+: Rent/Buy

“From Here to Eternity” comes to the screen as a supreme mob-inciter. It will wave furiously and long to cause an enormous stir — never too patriotically.

This film is sensationalism gone rampant with sex, cruelty and all the ruddy elements which make for what is known as rough, rugged, brutal appeal. It has to do with soldiering, but it dallies preeminently with sex, and is only in minor degree concerned with war. The picture assumes to delineate peacetime troop conditions, especially the conditions that existed in Pearl Harbor before Dec. 7, 1941. To say that it is rich in compassion would be false. There is far more of bitterness about the story as it is told. Take or leave it, “From Here to Eternity” goes all out in making the military situation look its worst.

Burt Lancaster and Montgomery Clift head the cast, though theirs are not the most unusual, even though important, assignments.

Deborah Kerr portrays the wife of Capt. Holmes, who leads her own love life where she can best find it, while her officer husband industriously adventures elsewhere. She and Lancaster, the top sergeant, join forces to become a red-hot romantic team, their scene on the beach being one to cause the screen to sizzle, and almost going overboard. (Read more) —Edwin Schallert

1954: ‘On the Waterfront’

27th Academy Awards — March 1955

Running time: 1 hour, 47 minutes.

Streaming: Prime Video: Rent/Buy | Apple TV+: Rent/Buy | HBO Max: Included

The leading antagonists in “On the Waterfront” are gangsters — members of the shape-up and shakedown racket which has terrorized the eastern seaboard for years — and still does, though in reduced degree. “Shape-up” is the term for preferential hiring of stevedores and other dockworkers; “shakedown” means exactly what it says, and it took — and takes — the form of kickbacks in “dues” to a “union” ruled by thugs.

The leading protagonists are a priest who fights back, the New York State Crime Commission, a punchy ex-pug (Marlon Brando) who is shamed and goaded into standing up to “the system,” and the girl (Eva Marie Saint) who believes in him. (Read more) —Philip K. Scheuer

1955: ‘Marty’

28th Academy Awards — March 1956

Running time: 1 hour, 29 minutes.

Streaming: Prime Video: Rent/Buy | Apple TV+: Rent/Buy

The simple story of a guy and a girl — neither regarded as very impressive per worldly estimates — is told with a sort of overwhelming humanness in “Marty.”

Undoubtedly the public will find themselves amazingly captivated by a production that has no cliches or gimmicks, but which instead sets forth feelingly an impression of the life led by Americans of Italian descent and other homely and quite understandable people that make up the solid foundations of life in this country.

The arresting thing is the casting of Ernest Borgnine and Betsy Blair in the starring parts.

Borgnine will henceforward be recalled as the good, honest, 100% human fellow, trying to discover a romantic life for himself, with plenty of handicaps, in a picture that may well be remembered as long as pictures themselves are remembered. And what will cause it to be remembered is its intrinsic and inspiring spell of the goodness that is to be found in unostentatious and sincere people. (Read more) —Edwin Schallert

1956: ‘Around the World in 80 Days’

29th Academy Awards — March 1957

Rating: G (1983 reissue).

Running time: 3 hours, 1 minute.

Streaming: Prime Video: Rent/Buy | Apple TV+: Rent/Buy

When Phileas Fogg and his servant Passepartout, their around-the-world journey begun, are sailing over the mountains that separate France and Spain, their balloon basket swoops close enough to a crag to enable Passepartout to scoop up a pailful of snow. He then produces a bottle of champagne from nowhere and places it in the pail to cool. In another jiffy, he and his master, sky high, are toasting one another and the success of their venture.

This is as good a scene as any with which to attempt to convey something of the antic spirit of “Around the World in 80 Days.”

Mike (Michael) Todd created it for his own amazement and now a sizable portion of that same world can share its assorted delights. The three things that make Todd’s picturization of Jules Verne’s prophetic novel of 1872 seem so fresh and different are the way in which it has been approached, the blown-up technical attractions and the surprises in the casting of the 40-odd “cameos” who pop up where and when you least expect them.

David Niven as Phileas Fogg and Mexico’s Cantinflas as Passepartout have made a triumphant virtue (always a risky business) of the cliché, and in techniques as far apart as their training — Niven as the apotheosis of the Englishman who understates it in words, Cantinflas as the sad eternal clown who pantomimes it in actions. (Read more) —Philip K. Scheuer

1957: ‘The Bridge on the River Kwai’

30th Academy Awards — March 1958

Rating: PG (1991 reissue).

Running time: 2 hours, 41 minutes.

Streaming: Prime Video: Rent/Buy | Apple TV+: Rent/Buy

When you see “The Bridge on the River Kwai” — and see it you surely will — you may be reminded, as I was for the first time in too long, that the potential of the cinema is practically limitless.

“The Bridge on the River Kwai” is an Anglo-American creation, though more Anglo than American. It was produced by “On the Waterfront’s” Sam Spiegel and bills William Holden above his co-stars, Alec Guinness and Jack Hawkins, but its primary power lies in the direction by England’s David Lean and the acting of Guinness as a typical Indian army colonel of the old Kipling school.

Japan’s indestructible Sessue Hayakawa is not far behind him as the commander, equally inflexible, of a jungle prison camp in World War II.

Lean’s brilliant realization of the novel and screenplay by Pierre Boulle may well become the stiff-upper-lip classic of its time, like “Beau Geste” before it. It was photographed in Ceylon (by Britain’s ace, Jack Hildyard) amid natural scenery of unearthly beauty, making greater the ironic contrast between it and the tragedy of men bogged down in a war stalemate. (Read more) —Philip K. Scheuer

1958: ‘Gigi’

31st Academy Awards — April 1959

Rating: G (1975 reissue).

Running time: 1 hour, 55 minutes.

Streaming: Prime Video: Rent/Buy | Apple TV+: Rent/Buy

Hollywood, which so often doesn’t, beats the French at their own game in “Gigi.” Mais oui! — the game of love (what else?).

You have a treat in store. It is a breathlessly lovely thing to look at, with exteriors filmed in Paris and interiors to match, as designed and dressed by Cecil Beaton; and the French have really extended themselves in providing traditionally great landmarks to meet the big-screen promise — the Bois on a Sunday afternoon, Maxim’s of “Merry Widow” fame, a restored Palais de Glace for skaters. And beautiful women!

“Gigi” is also enchanting aurally. Successively — and successfully — a novel by Colette, a French film of 1950, with Daniele Delorme, and an international stage hit (Leslie Caron in London, Audrey Hepburn in New York), it is now a movie with music ... and what music! Lyrics as well as screenplay are by Alan Jay Lerner and the melodies are by Frederick Loewe; and, in an entirely different milieu, gay Paree at its gayest, they have done as delightful a service as they performed for Shaw’s London in “My Fair Lady.”

Miss Caron is top-starred as Gigi. With her are Maurice Chevalier, the perennial spirit of the boulevard himself, as Honore Lachaille; Louis Jourdan as his nephew, Gaston; and Isabel Jeans and Hermione Gingold as Gigi’s aunt and grandmamma, respectively. Plus Eva Gabor, the gloriously unfaithful mistress of Jourdan. (Read more) —Philip K. Scheuer

1959: ‘Ben-Hur’

32nd Academy Awards — April 1960

Rating: G.

Running time: 3 hours, 42 minutes.

Streaming: Prime Video: Rent/Buy | Apple TV+: Rent/Buy

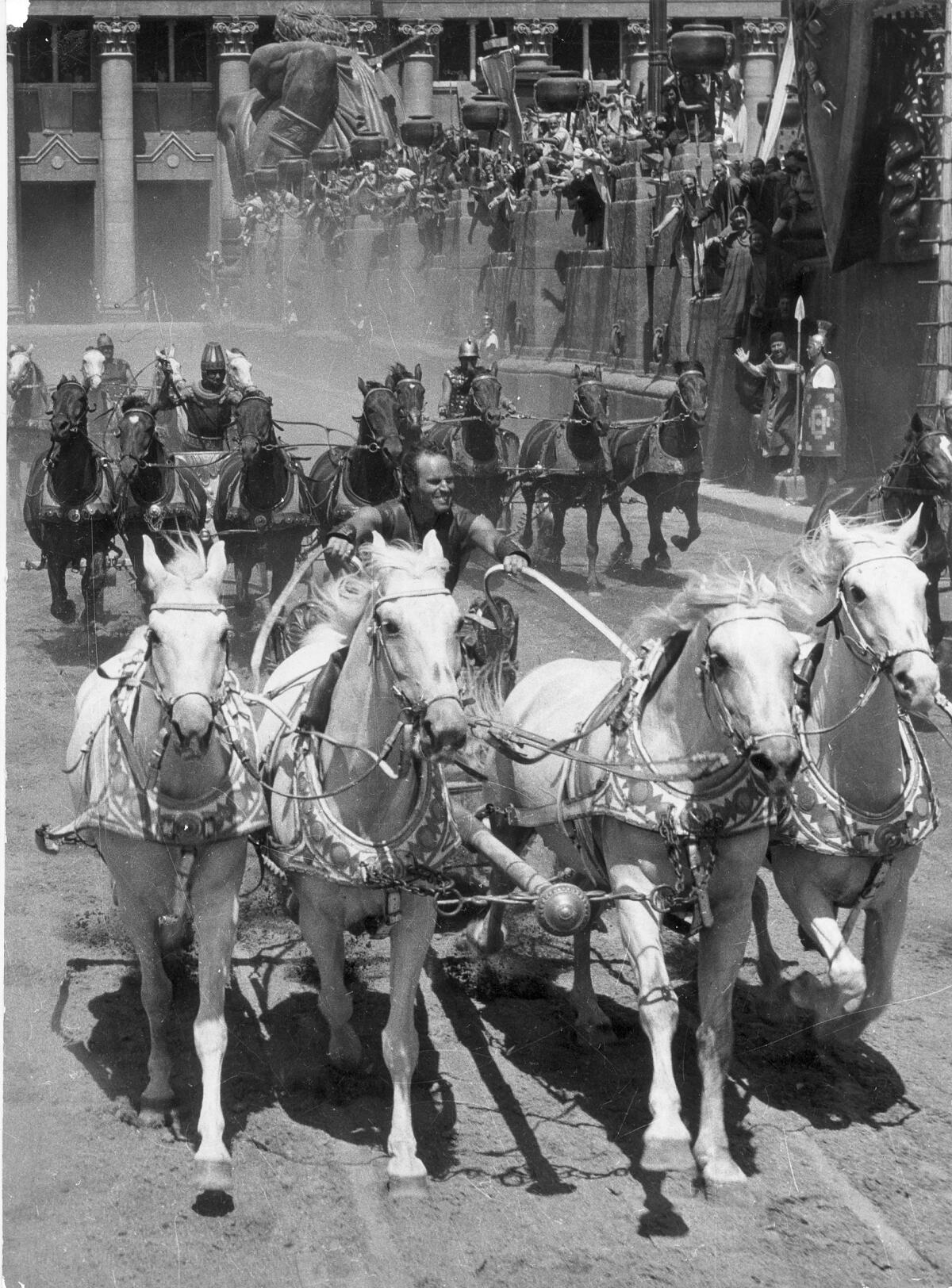

MGM has delivered the “Ben-Hur” it promised. It is, whatever the minor pros and cons that will rage over it, magnificent, inspiring, awesome, enthralling and all the other adjectives you have been reading about it.

Its race marks an all-time peak in action attained by any camera anywhere — 10 minutes of hurtling chariots, flying horses and berserk supermen. I doubt if old Jerusalem ever saw anything like this, but what would “Ben-Hur” be without it?

It is an epic saga of Judah Ben-Hur, the Jewish prince banished to Roman serfdom who after many vicissitudes returns to his people and is converted to Christianity. Charlton Heston is required to run an almost impossible gamut and just about does. (Read more) —Philip K. Scheuer

How to watch Oscar best picture winners through the decades

Intro and 1920s | 1930s | 1940s | 1950s | 1960s | 1970s | 1980s | 1990s | 2000s | 2010s | 2020s (and 2020 nominees)

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.