L.A.’s Marciano art museum will debut May 25. But first: A sneak peek

- Share via

Artist Jim Shaw has a cold. Curator Philipp Kaiser is jetlagged, having just flown in from Venice, Italy, the night before. And artist Sterling Ruby is a bit frazzled as he rushes into the lobby of the unfinished Marciano Art Foundation on this late spring morning.

A feisty wind blows through the freight entrance of this former Scottish Rite Masonic Temple, kicking up construction dust and rustling plastic tarps while buzz saws shriek in the background. A photographic mural of the artist Cindy Sherman dressed in ritualistic Masonic garb looms over the lobby, her piercing gaze seeming to suggest: Get it together, guys.

The new contemporary art museum from Guess co-founders Paul and Maurice Marciano, set to open May 25, is still in the throes of building renovations, but the installation of inaugural exhibitions is well underway. As crates are pried open and the paintings, sculpture, photography and multimedia installations from the Marcianos’ collection are configured, the scene is a little chaotic — and charged with excitement.

“It’s like a dream,” says Maurice Marciano, leading The Times on an early tour of the space, four years in the making. From the mezzanine, he surveys the lobby below, which is encased in gleaming travertine stone and gold mosaic tiles. “Hopefully people will discover artists here that they’ve never seen before. That’s the idea.”

The Marciano Art Foundation adds to L.A.’s quickly expanding museum landscape. The Broad museum opened in late 2015 in downtown L.A., across the street from the Museum of Contemporary Art. The non-collecting Main Museum made a soft debut in downtown’s Old Bank District in October. The Santa Monica Museum of Art will reopen this fall as the newly renamed Institute of Contemporary Art Los Angeles in the downtown Arts District, where the relatively new Hauser & Wirth gallery shows museum-level ambition. Not far away in Exposition Park, George Lucas’ $1-billion Museum of Narrative Art is planning a 2021 premiere. And the Los Angeles County Museum of Art last month revealed its latest designs for a $600-million makeover, with groundbreaking scheduled for next year.

Like the Broad as well as the Hammer in Westwood, the Marciano Art Foundation, on Wilshire Boulevard near Koreatown, will be free. It aims to distinguish itself with a collection of about 1,500 artworks, created in the 1990s or later, that juxtapose young and emerging artists with more established names.

On the day of the sneak peek, L.A. artist Alex Israel’s mural “Valet Parking” is being installed. Across four walls, it depicts leafy palms, giant cactuses, parking meters and other images from the streets of L.A. The piece showed at the Consortium, an art center in Dijon, France, in 2013, and Marciano bought it that year; now, however, the re-staging of the work is still a stretch of charcoal outlines, with loose artist’s sketches and open buckets of paint scattered on the floor as a scenic designer working with Israel adds color between the lines.

This sort of tumult is a theme, says Kaiser, who organized the inaugural exhibition. “Unpacking: The Marciano Collection” was inspired by a 1931 essay by German writer Walter Benjamin, “Unpacking My Library.” The piece explores the creativity unleashed in the messiness of unpacking, the chaos sparking new meaning among the objects. It’s a journey Kaiser embarked on when whittling the Marcianos’ collection down to about 120 works for viewing.

“The exhibition is threads that make sense, but it’s also loose and I’m not afraid of the loose,” says Kaiser, formerly senior curator at MOCA. “The title of the show, ‘Unpacking,’ is kind of nice because it’s conceptualizing randomness in a way.”

Kulapat Yantrasast, founder of the design firm wHY, preserved some original features of the 1961 Millard Sheets building, including exterior stone sculptures of pharaohs, saints and other historical figures as well as three of Sheets’ mosaics and one of his painted murals. The soaring ceilings and Masonic touches give the 110,000-square-foot space a temple-like feel. That’s appropriate, Marciano says, because more than anything, the Marciano Art Foundation is a house of worship, as he describes it, to the artists and to the last decade’s explosion of art production in Los Angeles.

Marciano says he feels a visceral connection to the art and artists here. There’s a relative youth and immediacy to the collection. While expanding it, Marciano visited artists’ studios to view works in progress, he says, while also serving on the board of the Museum of Contemporary Art, where he is board co-chair.

He purchased the foundation’s building for $8 million in 2013. Israel, a childhood friend of foundation deputy director Jamie G. Manné, suggested the location. The property is meant not only to showcase the collection but also to spark dialogue among the artists through exhibitions and events. Although Marciano declined to reveal the cost of building renovations, the value of the collection or the size of future acquisitions, commissioning site-specific works responding to the storied building will be central to the foundation’s mission.

The inaugural exhibition will feature several of these commissions. A sculpture garden in the entranceway will feature a 12-foot-high abstract piece made of found metal by New York artist Carol Bove, along with works by Thomas Houseago and Franz West. The foundation also will show Ryan Trecartin and Lizzie Fitch’s 49-minute, six-screen video, “Ledge,” which depicts the building prior to demolition and will be projected inside a sculptural tent.

The third floor of the foundation, more than any other area, highlights relationships between artists — connections that provided a map of sorts for Kaiser. Three bright galleries on one side showcase the more established artists in the collection. Abstract paintings by Christopher Wool and Albert Oehlen hang side by side. “They were good friends,” Marciano says. An adjacent gallery features paintings and sculptures by the late Mike Kelley and Ruby, who was Kelley’s student and teaching assistant.

“My God, a lot of this work I’m seeing here for the first time,” Marciano says, looking around. “Amazing.”

Ruby, in white painter’s pants and a baseball cap, walks in. Marciano slaps a hand on his shoulder as Ruby surveys the room. “Heeey. Do you like this?” Marciano says, like a proud papa. “Yeah, yeah,” says Ruby, darting his eyes around at his abstract, graffiti-inspired spray-paint landscapes hanging alongside Kelley’s work.

“It feels familiar, and that’s a good thing,” Ruby says of showing with Kelley. “But also, I remember a lot of our conversations, which were not always in agreement. And it makes me very aware that even though my work can hang in context with Mike, we are and were and will always be extremely different artists. And that’s a good thing too.”

In the distance is a giant baby-blue balloon dog sculpture. But it’s not one of the famous works by Jeff Koons. The piece is artist Paul McCarthy’s response to Koons’ balloon dog sculpture at the Broad museum. Whereas Koons’ sculpture is polished steel riffing on inflatable balloons, McCarthy’s work is a plastic, inflatable inversion; whereas the Broad holds the deepest collection of Koons’ work among U.S. museums and doesn’t own any McCarthy works, the Maricano Art Foundation owns six McCarthy works and isn’t featuring Koons in “Unpacking.”

As if on cue, McCarthy strolls in, stroking his bushy, snowy white beard while looking around. His sculptures are on view with works by Louise Lawler and Takashi Murakami, the latter a friend and colleague of McCarthy’s. Both of their work depicts pop culture, McCarthy addressing American icon Walt Disney and Murakami riffing on Japanese anime.

“It’s my belief that art is a discussion, that we talk to each other,” McCarthy says. “It’s kind of like, where [some artists] make pieces about a tree or nature or human beings, I make pieces about art — because it’s part of who I am and what I obsess on every day.”

The other side of the third floor, previously the Masons’ banquet hall, provides a vast 13,000-square-foot exhibition space showing younger and emerging artists in the center of the room, with more established artists along the periphery. Towering glass doors open to a lengthy balcony overlooking Hancock Park treetops.

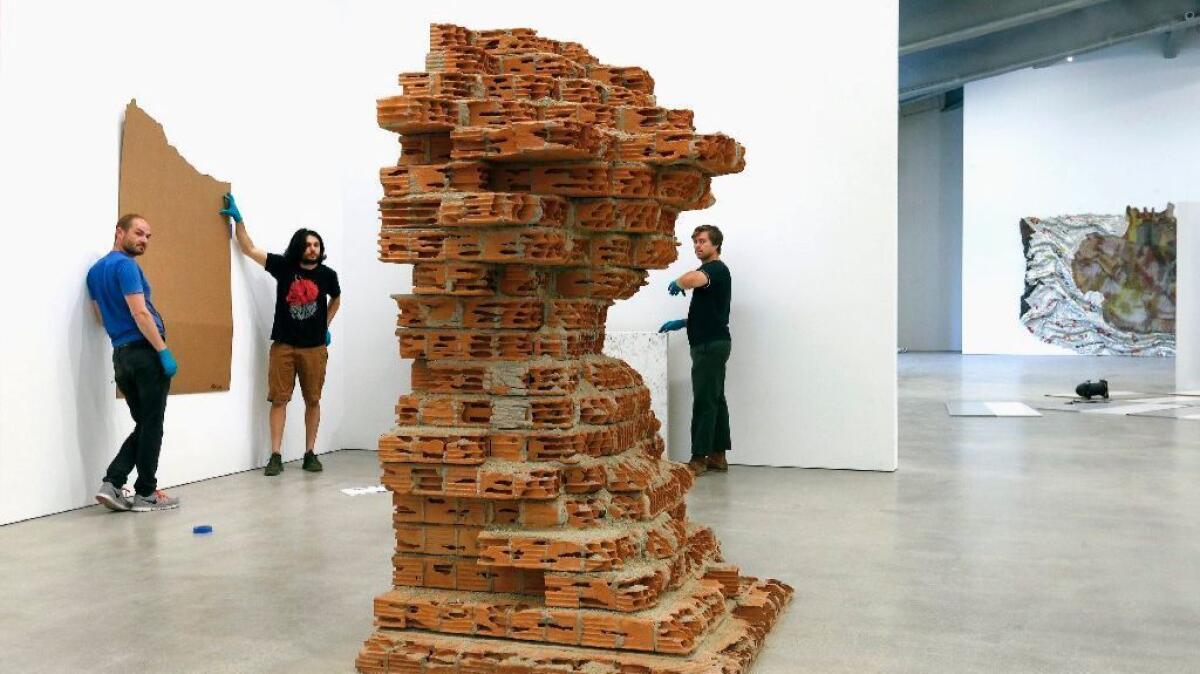

There are personal connections here as well. One area features works by Jonas Wood opposite those of his friend Mark Grotjahn, but the art in this part of the building is bound more by themes of dystopian architecture, entropy and ruin, as well as the visualization of process. Wall pieces — 300 pounds and architecturally inspired — by Oscar Tuazon hang near Damián Ortega’s sculpture of the corner of a dilapidated brick house and Jennifer Allora and Guillermo Calzadilla’s fossil-like gas pump. Elsewhere, Adrián Villar Rojas’ version of Michelangelo’s “David” lays on its side, as if deteriorating.

“It’s the ruin of a lost culture,” Kaiser says.

A small library on the mezzanine has a sampling of Mason relics left behind. Bard College art historian Susan L. Aberth curated this exhibit. The room’s original shelving now displays Masonic costumes — wigs, robes, hats and fake beards — along with old photographs, membership ledgers and tattered publications.

By the time the tour winds back downstairs to where “Jim Shaw: The Wig Museum” will be displayed in what had been the Masons’ 2,000-seat theater, Shaw has gone home to nurse his cold. But his presence is felt: Strewn all around are unopened crates and his artworks covered in tarps.

The L.A. artist’s first solo West Coast museum show is among the most site-specific work in the building. One installation in the exhibition, “The Wig Museum,” is inside a specially built structure incorporating wigs from Shaw’s collection along with those the Masons left behind. Elsewhere in his exhibition, Shaw will display painted plywood cutouts of figures conflating humans and technology, like a man-electrical tower hybrid, placed in front of hand-painted, fantastical backdrops that the Masons used in ritual performances.

The exhibition puts a fine point on the theatricality of the space.

“The building just inspired me,” Shaw says later by phone. “When someone gives you some money and a giant space and says ‘fill it up’ — and with the Masonic backdrops, I had the use of this already crazy imagery — it feeds upon itself and makes for a magical-thinking mirror land. You can extrapolate ideas and add to them. The possibilities are endless.”

Follow me on Twitter: @debvankin

ALSO

Jessie Homer French at Various Small Fires: In death, she finds life

Pippa Garner at Redling Fine Art: Vehicles for clever satire

‘The 14th Factory,’ despite all the hype, is just an $18 ticket to spectacle

Hollywood and art world stars turn out to honor Jeff Koons

At LACMA, the horror of 9/11 through the eyes of a Muslim artist

Beverly Center as art gallery? Big-name artists behind those construction barricades

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.