From 125th Street in Harlem, Thelma Golden has changed the face of art all over the U.S.

- Share via

If you were to describe the Studio Museum in Harlem by its physical size, you’d have to say it’s small.

Its home is unassuming — a turn-of-the-20th century commercial building on 125th Street in New York City whose Beaux-Arts design is dressed up with a modern entrance. And its collection is modest: 2,200 objects focused on art by African American artists over two centuries. (As a point of comparison, the Whitney Museum of American Art, also in Manhattan, has 23,000.)

This intimate scale can be surprising to the first-time visitor.

“Often, it makes me laugh when people who have never been to the museum would come visit,” says Thelma Golden, the museum’s director. “The two things people would often say is that they thought I’d be taller and that the museum would be much bigger.”

She grins.

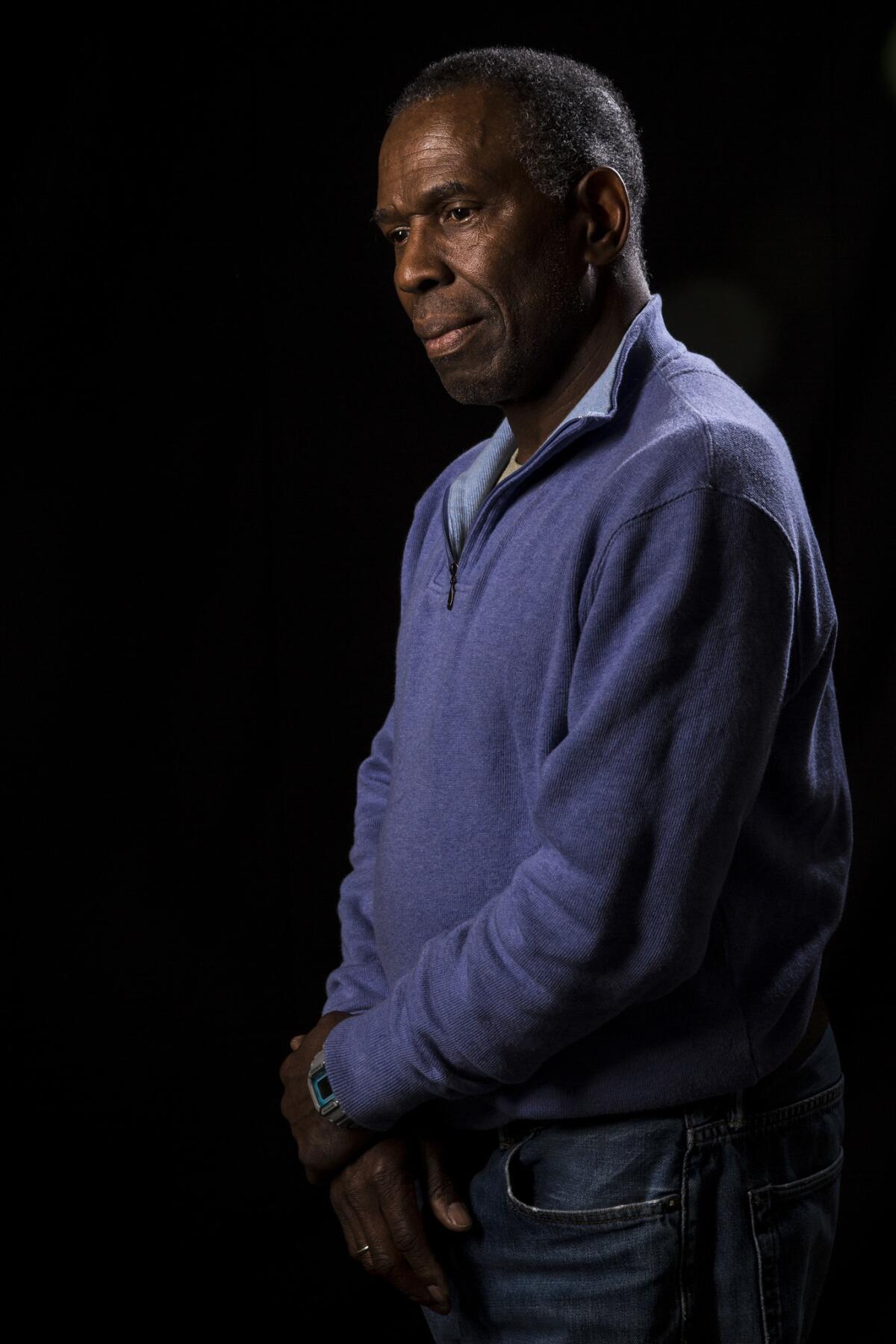

Golden is small, barely cracking 5 feet, a fact that is prominently noted in just about every profile ever written about her — profiles that also never fail to mention her meticulous fashion sense. (For our interview, she materializes in a bright floral jacket and a pair of sculptural animal print sandals.)

Being small, however, doesn’t mean lacking power. The Studio Museum’s reach extends far beyond the walls of its former bank building in Harlem. And Golden’s hand has been present in trailblazing exhibitions that have traveled all over the country and in the careers of countless artists and curators who have had their work nurtured by her institution at critical moments in their development.

These achievements are why Golden will be one of three prominent cultural figures, along with philanthropist Agnes Gund and sculptor Richard Serra, who will receive a 2018 J. Paul Getty Medal in a special event at the Getty Center on Monday evening.

“I don’t think you can say ‘African American art’ without saying ‘Thelma Golden,’” says James Cuno, president and chief executive of the J. Paul Getty Trust. “You can’t say ‘contemporary art’ without saying ‘Thelma Golden.’ You can’t say ‘Harlem’ without saying ‘Thelma Golden.’

“There isn’t a museum director who has done more for her institution than Thelma has done for hers.”

Seated poolside at the Standard Hotel in West Hollywood, where she has landed in advance of the medal ceremony, Golden is both humbled and proud as she considers her three decade-long career in the arts and her nearly two-decade stint at the Studio Museum, where she has served both as curator and director.

“If you look at the collection of the publications of the Studio Museum,” she says, “one would imagine that the Studio Museum is a much bigger, much richer institution.”

She pauses.

“I correct myself: The Studio Museum is big, and it’s always had an incredibly big ambition.”

The ripples of that ambition can be felt throughout the art world, where it is practically impossible to go a few feet without running into someone who has a connection to the museum.

Studio Museum exhibitions have appeared in Chicago, Boston, Philadelphia, Houston and Toronto. In Los Angeles, Studio Museum artist retrospectives and groups shows have landed at the Hammer Museum and the Santa Monica Museum of Art (now the Institute of Contemporary Art Los Angeles, or ICA LA).

The latter showcased the defining 2001 exhibition “Freestyle,” which explored how some black artists in the post-civil-rights era were moving away from direct representations of identity — a show that Times art critic Christopher Knight described as “engaging” and “provocative.”

“Freestyle” not only broke ground in the way in which it presented ideas of the “post-Black” but it also helped ignite careers, including those of installation artist Eric Wesley and painter Mark Bradford, both of whom are from Los Angeles.

I don’t think you can say ‘African American art’ without saying ‘Thelma Golden.’ You can’t say ‘contemporary art’ without saying ‘Thelma Golden.’

— James Cuno, president and chief executive, J. Paul Getty Trust

Bradford, who has skyrocketed to international fame for stormy, abstracted works that layer paint and old bits of signage, and who represented the U.S. at the 2017 Venice Biennale, says that Golden’s support has been critical to so many artists.

“For me what has always been special and important about Thelma is her passion to connect people, places and things,” says Bradford via email. “It’s very important for an artist to connect with people who are willing to help develop the whole practice.”

Certainly, to go to a Los Angeles museum this year has been to encounter Golden’s handiwork in some form.

At the Hammer Museum, artists Lauren Halsey and EJ Hill, both of whom completed residencies at the Studio Museum, were prominently featured in the “Made in L.A.” biennial, and both went on to win important awards in connection with that show. Across town at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Halsey had a simultaneous exhibition, in which she transformed a hallway into a psychedelic grotto that riffed on black mysticism and drew critical accolades.

Down in Exposition Park, at the California African American Museum (CAAM), Los Angeles painter Gary Simmons currently has a series of large-scale murals on long-term view that explore the early history of black film. Golden first worked with Simmons in the ’90s, when she was organizing exhibitions for a branch of the Whitney Museum near Grand Central Station, when he was an emerging artist and she a budding curator.

Her connections to L.A. reveal an engagement that extends well beyond the New York art world, which often seems to regard the Hudson River as some insurmountable border.

“There was never a time that I wasn’t here, thinking about artists here, and thinking about this city,” she says of Los Angeles. “My first professional experience with Los Angeles was when I was working on the 1993 [Whitney] biennial, which was led by Elisabeth Sussman and Lisa Phillips and John Hanhardt and myself. It was my involvement in that exhibition, and Lisa and John and Elisabeth’s commitment then to L.A. artists, that made me understand what were then these narrow ideas of primacy of the New York art world.”

That 1993 biennial, with its controversial explorations of race, identity and gender, remains a heated topic of debate (some of which centered on Los Angeles artist Daniel Joseph Martinez, who created a conceptual piece for that show that consisted of a series of museum admission badges that came together to read: “I can’t imagine ever wanting to be white.”)

Golden calls the exhibition a “transformative experience in my career” because it revolved around “thinking of the ways in which art and artists can exist in a museum space in a way that is radical and powerful and can create change because of the work.”

Golden’s influence, however, stretches beyond art, into the hard wiring of the art world itself.

Over the years, she has worked with, hired and nurtured curators who have gone on to shape institutions all over the country. In Los Angeles, that includes Naima Keith, who serves as deputy director of the newly ascendant CAAM; Christine Y. Kim, an associate curator at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, who was Golden’s collaborator on “Freestyle” during her time at the Studio Museum; Amanda Hunt, who oversees the education and public programs division at the Museum of Contemporary Art; and Jamillah James, who was tapped as curator at the ICA LA in 2016.

Keith worked as an associate curator at the Studio Museum for five years until 2016, and during her time there, she organized a retrospective of the works of California conceptual artist Charles Gaines — a show that ultimately landed at the Hammer and that was praised by Knight as the sort of experience that took a viewer to “unexpected places.”

“If you look at most job listings for an assistant curator, you’re assisting,” says Keith. “But at the Studio Museum, we’d be doing full-blown shows. It’s [Golden’s] realization that she can give us a level of experience that we wouldn’t otherwise have, and if we want to go on to work at larger institutions, we need that experience.

“When I approached her about Charles’ show, I was a young whippersnapper. And that it ended up being a huge success is a testament to her confidence in us.”

Golden sees in her own experience the importance of being afforded an opportunity to learn and to grow.

As an undergraduate student at Smith College in Massachusetts in the ’80s, she interned at the campus museum and got to work on an exhibition about Dorothy Miller, the pioneering female curator who helped make the case for a generation of Modern artists at New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

While in college, she also served as a summer fellow at the Studio Museum when it was under the direction of Mary Schmidt Campbell, an important African American scholar and art historian who is now the president of Spelman College. There, Golden cataloged the papers of 20th century painter and collagist Benny Andrews, who had kept diligent record of the black art milieu.

This was followed by various institutional positions, including a stint working at an arts center in Queens for curator and historian Kellie Jones who would later be named a MacArthur Fellow and organize the Pacific Standard Time exhibition “Now Dig This! Art and Black Los Angeles, 1960-1980” at the Hammer.

“Kellie taught me what it meant to do the work,” says Golden. “She had incredible ideas and amazingly ambitious vision. And she had few resources, but it never stopped her from doing the best work.”

It’s a formation she is trying to give another generation of curators — at a time in which museums are actively working to diversify their ranks.

“What I work hard to do is continue to offer that sense of possibility to young professionals in this field,” she says. “The field needs all of our voices.”

Beyond the Getty Medal, 2018 is a significant year for Golden as well as her institution. This year, the Studio Museum marks its 50th anniversary. Next year, she expects to break ground on a new museum building designed by David Adjaye (the architect behind the acclaimed National Museum of African American History & Culture in Washington, D.C.).

“We had long outgrown our building,” she says. “It served us so well. I have lots of nostalgia for the physical space. But this is also about what institution-building means, about permanence, about what it has meant to live in Harlem for 50 years.”

Early last year, Thomas Campbell, director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, abruptly resigned under pressure over financial issues. Among the names bandied about for his replacement was Golden. The news got art circles chattering over the possibility that one of the country’s most storied encyclopedic museums might be led by an African American woman.

When I ask her if she considered the job, Golden politely declines to discuss it, and deftly turns the discussion right back to her ambitions for the Studio Museum.

“What I can say is that I am in awe that I get the privilege of stewarding this institution,” she says. “I don’t know if I will see the results of some of the actions that are happening at this moment, but I have to commit to them deeply.”

Having power isn’t always about being big. It’s about wielding it wisely.

ALSO

Naima Keith’s Electric Vision: Giving the California African American Museum a Jolt of Energy

D.C.’s new African American museum is a bold challenge to traditional Washington architecture

How the dense grids of artist Charles Gaines took the ego out of art

His art centers on African American actors whose film titles ‘Fade to Black’

Cultural Evolution in ‘Freestyle’

Sign up for our weekly Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

[email protected] | Twitter: @cmonstah

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.