Newsletter: Can Major League Baseball step up to the plate on climate change?

- Share via

This is the Nov. 18, 2021, edition of Boiling Point, a weekly newsletter about climate change and the environment in California and the American West. Sign up here to get it in your inbox.

I’ll never forget the moment when it finally hit me how serious the pandemic was going to be. I was standing outside a dairy farm in California’s San Joaquin Valley, learning about methane emissions from cow poop, when I saw the news on my phone: Major League Baseball was canceling the remainder of spring training. The start of the regular season would be postponed.

If you follow me on Twitter, you already know I’m a huge Dodgers fan. Not being able to attend games in 2020 was painful, although thank goodness I wasn’t dealing with anything worse. Returning to Dodger Stadium this summer was an absolute joy, and I’m hoping to see some road games again in 2022 — maybe I’ll fly to Atlanta, or Kansas City, or St. Louis.

So it feels strange to say this, but here goes: There was a silver lining to last year’s disruptions to professional sports.

New research from Seth Wynes, a postdoc at Concordia University in Montreal, found that scheduling changes designed to limit the spread of COVID-19 significantly reduced climate pollution from sports air travel. By scheduling more games between teams in the same geographic regions, increasing the number of back-to-back contests between the same teams and canceling overseas games, America’s four major men’s sports leagues slashed emissions by 26% per game in the regular season, Wynes found.

The reductions were biggest in the National Hockey League, which saw planet-warming carbon dioxide emissions from air travel fall by 50% per game in the regular season compared with 2018. Next came MLB with a 22% drop in carbon emissions, followed by the National Basketball Assn. at 15% and the National Football League at 6%.

Here’s the study, published this week in the journal Environmental Science & Technology. It left me feeling torn.

On the one hand, airplanes are a major contributor to climate change, accounting for about 2.5% of global carbon dioxide emissions. And they’re tough to decarbonize, because cleaner fuels are still prohibitively expensive, and electric planes can fly only so far. Maintaining a livable climate will almost certainly require cutting down on air travel, at least for the foreseeable future.

On the other hand ... as a baseball fan, I don’t want future seasons to look anything like 2020. In addition to not having fans in the stands — which is not what Wynes is suggesting — MLB ballclubs played teams only within their own geographic regions, to limit the need for lengthy flights. That means the Dodgers never played the St. Louis Cardinals, for instance, or the New York Mets. It took some of the fun out of the regular season — much as I enjoy Dodgers-Giants games, I only need so many of them.

The NHL also limited regular-season games to teams within the same regions. The NHL and NBA, meanwhile, took a page from MLB’s non-pandemic playbook by scheduling more series with consecutive games between the same teams. The NFL canceled games in London and Mexico City.

If those scheduling changes had been in place in 2018, Wynes estimated, overall emissions would have been 22% lower.

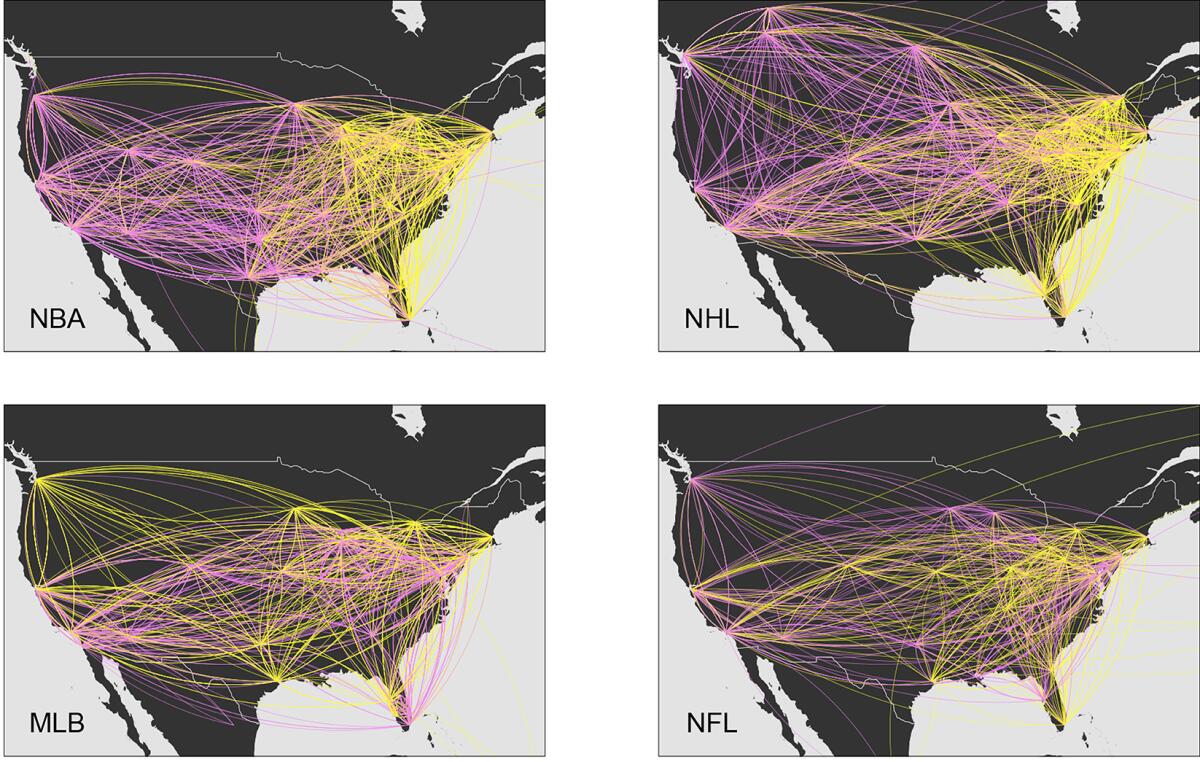

Here are some maps that Wynes created, showing all flights taken by NBA, NFL, NHL and MLB teams during the 2018 season, including for preseason and postseason games. The different colors represent trips taken by teams in different conferences:

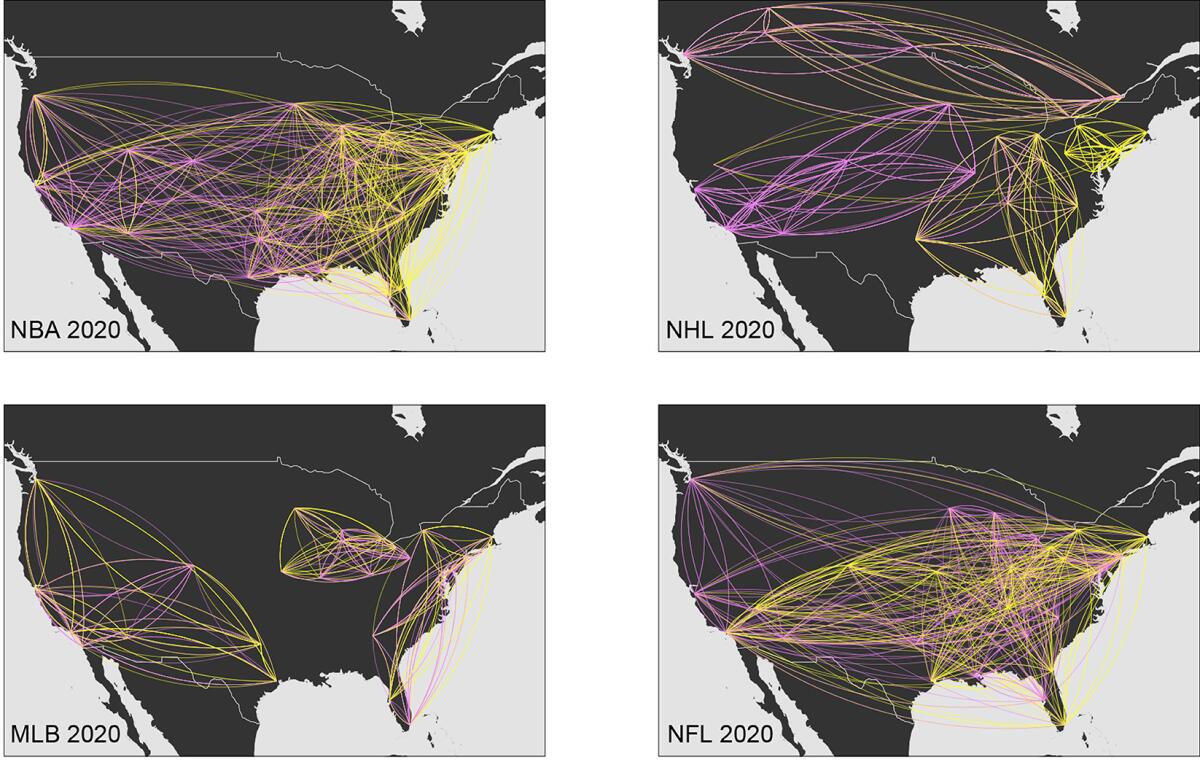

That’s a ton of flights. Here are the same maps for 2020:

There are a lot fewer flights, largely because the NBA, NHL and MLB played shortened seasons. But you can see the impact of regional scheduling for baseball and hockey — far fewer lines stretching across the map (with the exception of some lengthy flights across Canada in the NHL, since Canadian teams were grouped together to limit border crossings).

To be clear, all those trips are a drop in the bucket of global air-travel emissions. But Wynes thinks the leagues could have an outsize impact on the climate crisis. He said professional sports teams have a powerful opportunity to lead by example.

“Athletes are important role models. What they do matters,” Wynes said.

I asked him if he thought people would fly less if their favorite players did the same. He suggested I think about it differently.

“If you picture a world where our culture shifts quickly and we actually tackle climate change, and manage to amazingly do this rapid decarbonization and achieve 1.5 degrees — in that vision of the world, do you see celebrities and major league sports and other elites and role models just continuing in their status quo?” he asked. “That’s really unlikely. And so I would see it as being a meaningful part of a cultural shift that would need to take place.”

I also reached out to representatives of the NBA, NFL, NHL and MLB, asking them if they’d like to comment on Wynes’ study and what steps, if any, their leagues have taken to reduce climate pollution from air travel.

NBA spokesman Mike Bass told me teams will travel an estimated 43,000 miles on average this season, down from an expected 46,000 miles last season (before COVID-19 got in the way). He said the NBA had scheduled more series, fewer single-game road trips and more teams playing both the Clippers and Lakers when they come to L.A. (and both the Knicks and Nets in New York).

“Environmental sustainability is a priority for the NBA and our teams, and we continue to proactively explore ways to reduce our carbon footprint,” Bass said in an email. “For the 2021-22 season schedule, we were able to make adjustments that resulted in reducing the estimated average miles traveled per team to the lowest ever for an 82-game season.”

Disappointingly, none of the other leagues got back to me with responses.

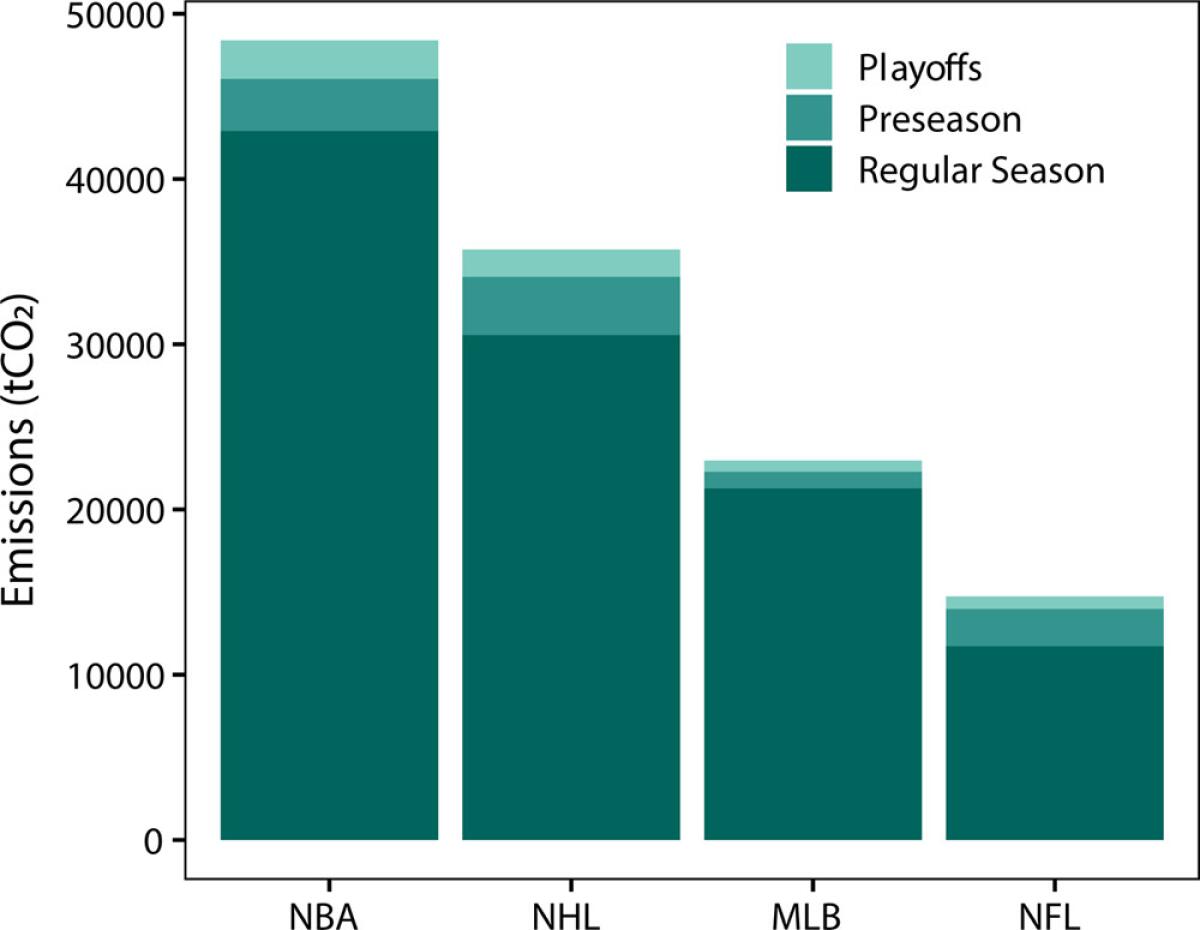

I was, however, struck by this chart from Wynes’ study, estimating overall air travel emissions from each league in 2018:

It’s not surprising to see the NFL with the fewest emissions, because football teams play so few games. MLB has the second-lowest total because despite having the longest schedule, teams typically play three-game series before flying to their next destination.

One reason the NBA is the top polluter, Wynes wrote, is because basketball teams “travel in larger aircraft with higher rates of fuel burn” — part of a trend in which some sports franchises are buying more luxurious jets to entice free agents to sign with them.

Switching basketball teams to smaller aircraft could slash the NBA’s air-travel emissions by 26%, Wynes estimated. He also found that reducing the length of the regular season by 10 games — which the NBA has considered — could cut emissions by 11%.

I’ll leave it to basketball fans to assess whether that’s a good idea. But as a baseball fan, I’m still not sure how I feel about all this.

The 162-game schedule isn’t necessarily sacrosanct — my grandfather grew up with 154 games — but I wouldn’t want to see it shortened too much. I also want to watch the Dodgers compete against teams from across the country, and not just during the playoffs. Maybe they could play three games each against the Cardinals and Mets during the regular season, rather than six.

One way or another, professional sports will have to get serious about reducing emissions, and not just out of a sense of goodwill. Higher outdoor temperatures, less reliable snowpack, more pervasive wildfire smoke, bigger storms and other global warming impacts are already hampering athletes around the world. Personally, I’ll never forget attending the hottest game in World Series history. On a late-October day in L.A., the temperature was 103 degrees Fahrenheit at 5:11 p.m. for first pitch.

That was in 2017. The world is even hotter now, and yet this year is likely to be one of the coldest for the rest of my lifetime and yours.

Here’s what else is happening around the West:

TOP STORIES

A first-of-its-kind analysis from the L.A. Times shows how freeway construction projects continue to tear up Black and Latino communities. My colleagues Liam Dillon and Ben Poston tracked highway expansions from California to Florida, finding that more than 200,000 people have lost their homes to federal road projects over the last three decades, with some of the largest projects disproportionately displacing people of color, including in Los Angeles County. Here’s a detailed explainer from Ben and Liam on how they did the analysis, as well as a brief history of racist freeway construction and redlining. These highway projects not only displace families but also spew hazardous air pollution and lock in our dependence on cars, trucks and sprawl.

There’s a good chance the next pandemic will emerge from the Amazon, as Brazil allows the rainforest to be slashed and burned to make room for more farms and cities. Read this powerful story by The Times’ Kate Linthicum, Emily Baumgaertner and Ana Ionova, told through the eyes of a 10-year-old girl, and keep in mind that deforestation is terrible for climate too, releasing huge amounts of carbon. Also check out these moving photos by Luis Sinco showing what life is like at the edge of the Amazon and why, in some cases, people are burning down the rainforest because they see it as their best shot at a better life.

For years, people have talked about extracting lithium at the Salton Sea — and now it’s finally close to happening, along with the first new geothermal power plant in a decade. Here’s my story from California’s Imperial Valley about a project backed by General Motors that could produce round-the-clock clean electricity for California and loads of lithium for electric car batteries. The project’s few environmental drawbacks stand in stark contract to the planned Thacker Pass lithium mine in Nevada, which faces intense opposition from tribes and conservationists, as Cayte Bosler chronicles for Inside Climate News. And it’s not just lithium mining causing controversy; the clean energy transition will require lots of copper. Rural New Mexico residents worry that proposals to expand copper mining could poison their groundwater, as Gitanjali Poonia reports for New Mexico In Depth.

DROUGHT, HEAT AND FIRE

California, Arizona and Nevada are negotiating a $100-million plan to keep more Colorado River water in Lake Mead. The goal is for farms, cities and tribes to use less water and thus avoid the need for painful mandatory cutbacks if the reservoir drops too low, my colleague Ian James reports. Paying people to conserve will hopefully work better than asking them nicely; Ian also reports that Californians reduced their water consumption just 3.9% in September, down from 5% in August and far short of Gov. Gavin Newsom’s 15% goal. With California facing the prospect of a major reservoir, Lake Mendocino, running dry for the first time, as Kurtis Alexander reports for the San Francisco Chronicle, aggressive water conservation is more vital than ever.

California lawmakers want to rank heat waves like hurricanes, in hopes of encouraging people and local governments to take them more seriously. You might remember I wrote about this idea last year; it’s now the subject of legislation following The Times’ investigation into extreme heat, my colleague Alex Wigglesworth reports. Finding ways to protect people from worsening heat waves is especially needed in the 47 L.A. County communities identified in a new report as most imperiled by climate change, Hayley Smith writes. More public parks offering shade and green space would help those neighborhoods and others cope with heat. If you want to help, Rachel Schnalzer has a great explainer on what you can do to get a public park built in Los Angeles.

Sequoia National Park has partially reopened after a fire, but some sequoia groves are still burning. “Realistically, some of these pockets could burn all winter long, even with snow,” one official tells my colleague Lila Seidman. In other wildfire news, I’d recommend this powerful documentary by The Times’ Claire Hannah Collins and Erik Himmelsbach-Weinstein, on formerly incarcerated Californians learning to fight fires because they want to serve — and all the hurdles society throws in front of them.

AROUND THE WEST

The National Park Service conducted an extensive study of widespread harassment within the agency after a damning investigation by High Country News — then buried it for years. The findings are only now coming out thanks to reporting by Lyndsey Gilpin, who writes that the study’s authors heard from hundreds of Park Service employees about workplace harassment and retaliation, with many “citing racism, sexism and discrimination against those with disabilities and LGBTQ+ employees.”

The Biden administration plans to ban new oil and gas leases within 10 miles of Chaco Canyon National Historical Park in New Mexico, to protect Ancestral Puebloan sites scattered across the region. Here’s the story from Theresa Davis at the Albuquerque Journal, who writes that tribal activists and conservationists had pushed for the leasing ban. At the same time, the Biden administration held the largest offshore oil and gas lease sale in U.S. history this week, opening up 80 million acres in the Gulf of Mexico, Chris D’Angelo reports for HuffPost. More than 1.7 million acres sold — still a big number, D’Angelo writes.

It seems Utah lawmakers are trying to impede L.A.’s ability to switch from coal to natural gas (and eventually hydrogen) at Intermountain Power Plant. Details here from Brian Maffly at the Salt Lake Tribune, who notes that the surprise last-minute bill sailed through the Legislature right as Intermountain Power Agency prepared to issue $2 billion in bonds to finance the coal plant conversion. To get up to speed, see my latest coverage of the coal plant. I’m told by folks at Intermountain Power Agency and the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power that they’re figuring out how to move forward. I’ll continue to track this.

POLITICAL CLIMATE

While some of the side deals at the Glasgow, Scotland, climate summit represented progress, the overall agreement produced by the nations of the world was a disappointment. That’s the final judgment of The Times’ Anna M. Phillips, who writes that we are still headed for a dangerous level of warming. (For a somewhat more optimistic assessment, see this piece by David Roberts.) A major reason the summit wasn’t more successful was continued tension between the U.S. and China. Chris Megerian notes that the countries did, at least, announce a climate agreement at the last minute, although details were scarce.

President Biden signed the $1.2-trillion infrastructure bill, which includes a whole lot of climate funding. Biden planned to visit General Motors’ electric vehicle assembly plant in Detroit to highlight the bill’s $7.5-billion investment in EV charging stations, my colleagues Arit John and Erin B. Logan report. California is expected to get $384 million of that funding, along with $80 million to mitigate wildfires and other disasters, $9.45 billion for public transit and $3.5 billion for cleaner drinking water, Erin reports. The state’s long-awaited bullet train might get a few billion dollars, Ralph Vartabedian reports — helpful, but not a game-changer.

As director of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Martha Williams would oversee 8,000 employees, 560-plus national wildlife refuges and implementation of the Endangered Species Act. Michael Doyle wrote an interesting story for E&E News on Biden’s nominee to lead the wildlife agency, focused on Williams’ history of consensus-building in Montana and Washington, D.C.

ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE

The awful stench in Carson is finally starting to diminish, although it sounds like officials still don’t have much idea what’s going on. Here’s the latest from my colleague Andrew J. Campa. And even after the smell subsides, Carson will still be plagued by air pollution from oil refineries, trucks and the nearby ports. As Times columnist Steve Lopez writes, “Most of the environmental hazards in the Carson area are tied in one way or another to fossil fuel consumption and to catastrophic climate change.”

Clean air activists say a recent spell of especially bad air pollution in Los Angeles may have been caused by the backlog of cargo ships idling off the coast. My colleague Nathan Solis explores whether congestion at the ports is to blame for the hazy skies that blotted out the sun earlier this month. An inversion layer was at least partially to blame too, Paul Duginski writes.

Tight oil supplies, high demand and rainfall that disrupted refinery operations are to blame for record-high gasoline prices in California. So writes The Times’ Hayley Smith. Most importantly for this newsletter, an energy economist told Hayley that the only long-term solution is to drive down demand for oil. Also relevant: President Biden asked the Federal Trade Commission to investigate high gas prices, citing what he called “mounting evidence of anti-consumer behavior by oil and gas companies.”

ONE MORE THING

A follow-up to the last few editions of Boiling Point: If you don’t subscribe to The Times and couldn’t read my story on the fierce battle over the future of rooftop solar in California, you’re now in luck: We’ve taken the piece out from behind the paywall. So go ahead and read it here. If you decide afterward that you want to support this kind of journalism, please do subscribe.

Still not convinced? Then listen to my wonderful colleagues Ron Lin, Alex Wigglesworth and Rosanna Xia talk drought, fire and floods — and debate the proper use of the term “mudslide” — on our daily podcast, The Times, with host Gustavo Arellano.

We’ll be back in your inbox next week. If you enjoyed this newsletter, please consider forwarding it to your friends and colleagues.