- Share via

This story is part of our issue on Remembrance, a time-traveling journey through the L.A. experience — past, present and future. See the full package here.

You never forget your first heartbreak. It was February 2007. I was 15, a high school sophomore. I’d been burned before, but not like this. This was “Gossip Girl.”

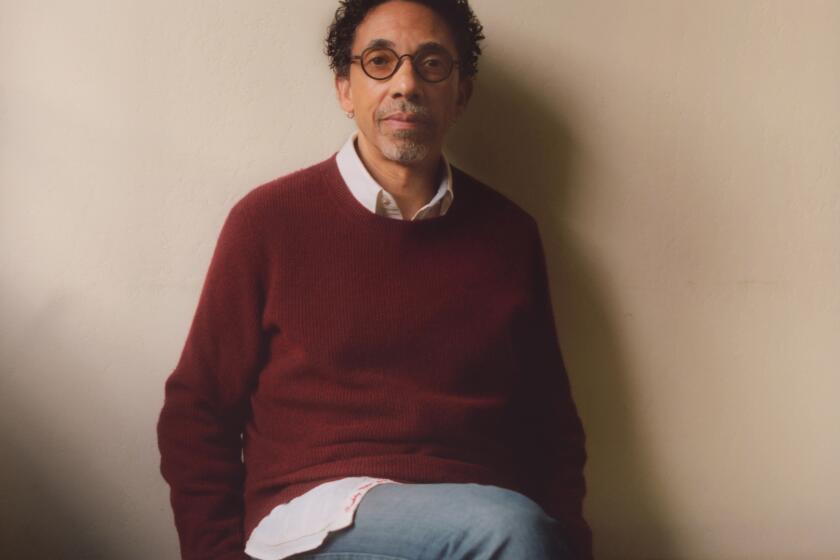

I spent the month auditioning, again and again, to play Jenny Humphrey on the iconic show. For weeks, I was the favorite. Then I didn’t get the role.

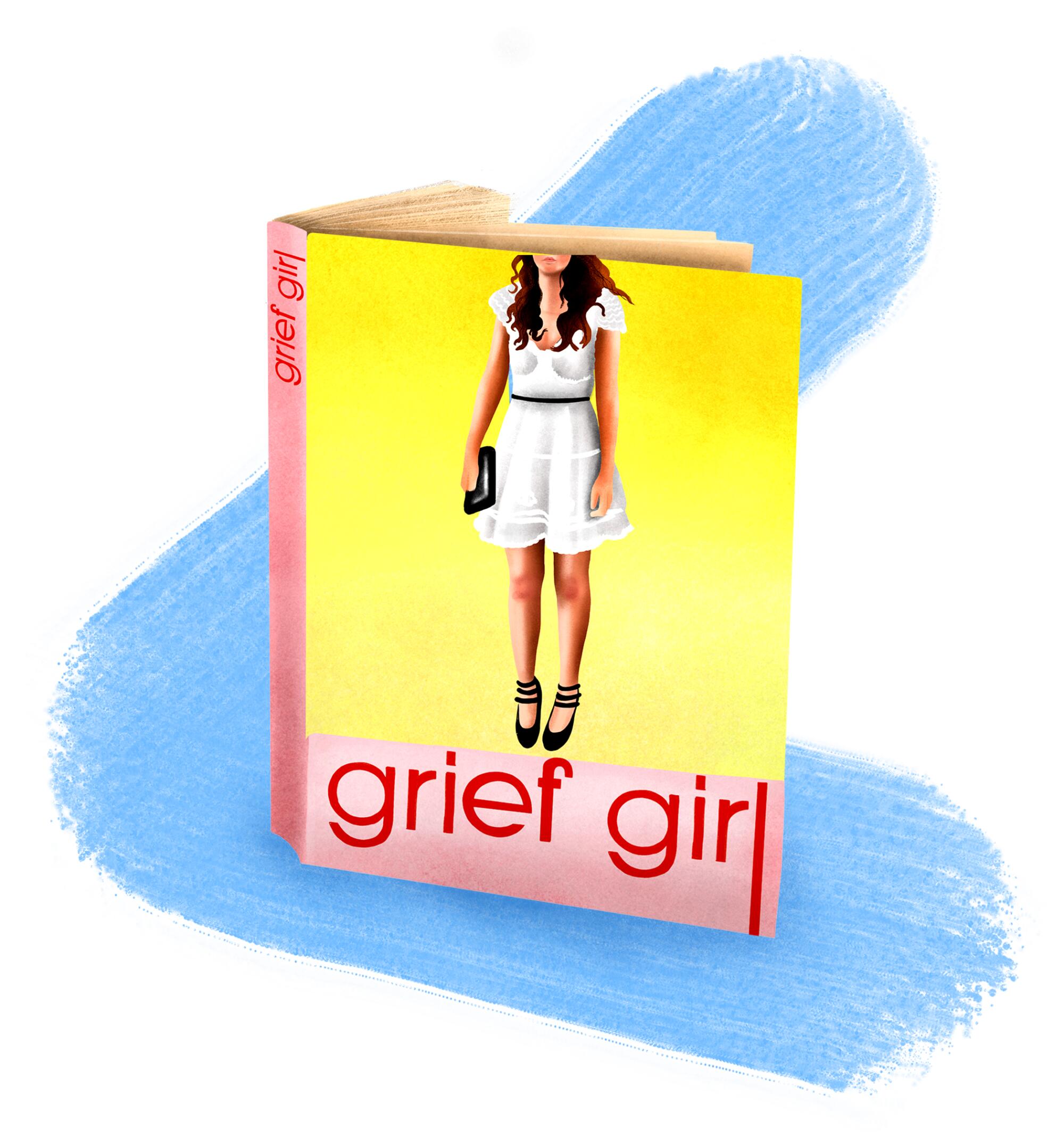

My love affair with Hollywood began in 2001, after my family paid to go on a Caribbean cruise hosted by the Olsen twins (long story). Throughout middle school, I acted on TV, attended film premieres, accepted free swag and, in my downtime, curled up with the rich, hot, traitorous Upper East Siders from the “Gossip Girl” books. If it were possible to overdose on materialistic teen fantasy, I’d be dead.

Not getting “Gossip Girl” sucked in a very specific way that’s since been encapsulated in a viral tweet: “If you live in LA long enough you’ll see someone who hurt your feelings on a billboard.” It sucked so much I wrote about it the following year, for my college admissions essay. Maybe I wanted to clarify that my value as an artist isn’t only defined by the work people end up seeing. Maybe I wanted to show off that I’d gotten so close to a shiny job.

Either way, I’ve always remembered the essay as a symbol of a transitional life moment: when not getting cast in “Gossip Girl” inspired me to disown my former celebrity-obsessed self and take on a pretentious intellectual persona who liked only Bob Dylan (and sounded like someone badmouthing an ex they can’t admit they’re still in love with).

It wasn’t until I started piecing it all together below — my college essay (in italics) along with journal entries and old emails my mom never deleted — that I learned the real reason February 2007 was so pivotal for me.

C-Double-Who?

I don’t worship the scandalous fiction that The CW pumps into its viewers’ minds, but as a young actress, I audition to be part of it.

Jan. 29, 2007: After school, I go on my first audition for “Jenny,” which I have low expectations for because I don’t look like the character in the book, who has huge boobs. I have long, scraggly curly hair that I either flat-iron or don’t brush, one blue flowy Free People top I feel pretty in and horrifying body insecurity due to some fresh stretch marks on my ass, which has never been touched by another human being despite my obsessive crush on a junior stoner drummer with long hair. Finding out “Gossip Girl” wants to see me again makes up for all of this.

I don’t want a cult following of adolescents but I invest effort and emotion into every one of my auditions. The closer I get to being cast, the more it hurts when the carpet is ripped from beneath me, regardless of the project.

Jan. 31, 2007: My grandma — my mom’s mom — dies at 84, after declining to be put on life support in a big brown brick building on La Brea, which looms over my route to my favorite West Hollywood lunch spot for overpriced salads. As a Holocaust survivor, she instilled in our family a method for coping with life’s harsher blows: Some things are just too painful to talk about.

When I absolutely, necessarily, obligatorily had to watch the pilot episode of “Gossip Girl” on TV, it was for a different reason than that of my peers. As I watched it explode into my generation’s pop culture and trickle into kids’ brains throughout the country, I remembered all of the auditions I’d had for the Jenny character and all of the executives I’d met.

Feb. 5, 2007: I leave a bungalow on a studio lot to learn that my dog, who I refer to in my journal as “my puggy Teddy Bear,” died. I’d been doing a callback for the Patricia Arquette show “Medium,” and my mom didn’t want this news to affect my performance.

Feb. 6, 2007: On the way home from my “Gossip Girl” “work session” with the director and creator (to prep me to perform for studio executives), I journal that I have a “really tight feeling inside my chest.” My dad tells me it’s anxiety and to try meditation. So I meditate, a.k.a. obsess over why the sexually active drummer I’m in love with isn’t throwing himself at my Uggs after months of my prolonged, ignoring-him-based flirting.

I’d known that the show would be as shallow and unfulfilling as it would be popular but I auditioned because I’d read the books and idolized its unrealistic characters. Jenny was the only one rooted in reality; in a world glorifying the unattainable, she was someone real whom girls could look up to and not change themselves to emulate. My creativity was built up, and my encouraging message needed to be spread.

Feb. 8, 2007: I audition for the “Gossip Girl” studio executives. My mom writes in her notes that casting “let 3 other girls go,” making me the “favorite for Gossip Girls.” A brief hit of bliss. Then, on THE SAME DAY, I journal: “I still have this feeling inside of me and I just want it to go away. My mom says she has it too but it goes away when she exercises so we’ve been going to the gym and I thought it was working for me but I could still feel it while I was on the elliptical today.”

Feb. 10-21, 2007: In addition to four “Gossip Girl” appointments, high school, multiple DEATHS and SEVEN OTHER AUDITIONS, my mom and I also FLY ACROSS THE COUNTRY TO FILM “LAW & ORDER.” I play a Christian girl whose dad burns down a church after she gets chlamydia from her teacher.

But it wasn’t. My only competition left after two months of weeding out hopefuls was the beautiful, heavily made-up, blond antichrist Taylor Momsen. She was cast as Jenny, and my agents sent me on other auditions as if nothing noteworthy had happened. Objectively, “Gossip Girl” had been just another audition. Personally, it had been an opportunity to embody a character different from any other on the show, to reassure ordinary, insecure viewers of their worth.

Feb. 22, 2007: I’m in a parking structure at LAX after returning from “Law & Order,” watching my mom cry out in a primal wail as she collapses to her knees. She’s just gotten the call that her brother is dead at 50. After years of drug abuse, his heart gave out.

March 1, 2007: I journal about my uncle’s funeral: “My cousin, after years of begging her father to stop taking drugs, wore an expression of utter defeat and heartbrokenness. At dinner, she did not eat anything. She turned to cry in my mother’s arms and begged my alcoholic uncle to not repeat the mistakes of his brother, her dead father.”

I don’t remember this. Not the funeral, not this brutal exchange, not how I felt about it, nothing.

My friends make fun of “Gossip Girl” and send me pictures of Taylor Momsen supposedly on drugs, but that’s not what I want.

What I remember is the “Gossip Girl” network test on March 2, 2007: Before the final audition, I’m asked to schedule another work session, and I SAY NO. I’m probably just exhausted but I feel overconfidently, exasperatedly like, “No, I DON’T need the creator of this show’s help. I’m good, bitch.”

At some point, I fight with my mom about my hair and makeup. Parents are usually telling teenage girls to wear less makeup but I feel ready for my close-up — bare-faced and scraggly-haired, baby. I’m shocked when a blond 13-year-old with a smoky eye walks into the audition waiting room.

But I know the part is mine. It has to be. Because the high of “Gossip Girl” will make up for all of my loss, terror, confusion and pain.

We get the call on our drive home. It’s not going my way. My mom — who has been shuttling me around Southern California and New York like she didn’t just lose her mom and brother — snaps, “Next time, you’re going to the work session,” and my confidence shrivels into nothing as I try and fail to understand what’s wrong with me so I can make sense of all of this.

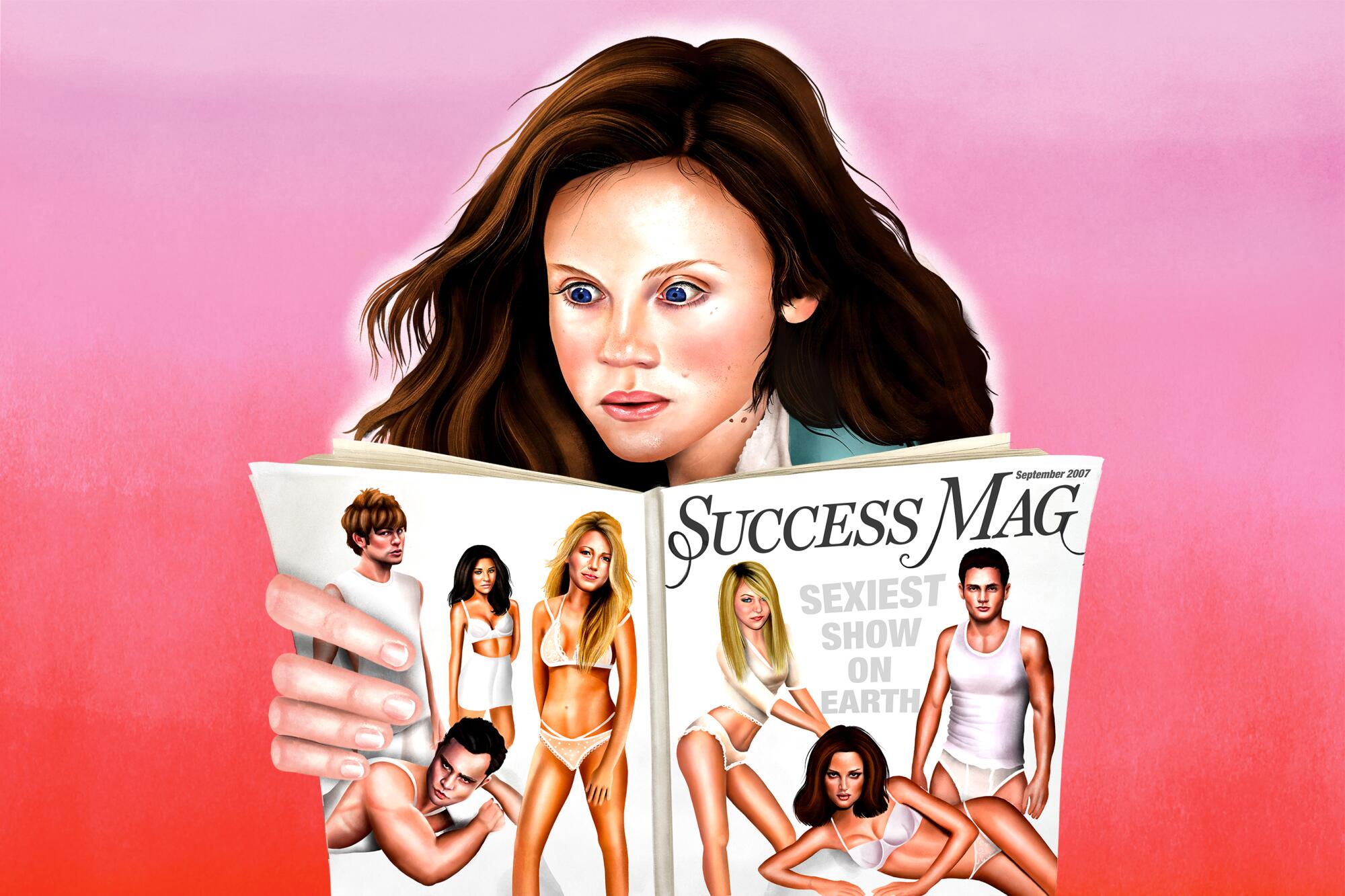

I want to have not seen the New York Magazine cover on which 14-year-old Momsen was clad only in underwear.

September 2007: It isn’t until months later when I see the New York Magazine cover of the smoking-hot cast lying in bed wearing LINGERIE that it dawns on me: I WASN’T HOT ENOUGH.

THAT’S what’s wrong with me. THAT’S what’s stopping me from having a perfect life. At some point, everyone around me started banging while I’m still reading about banging in YA books.

I’m still petrified of sex, but after “Gossip Girl” I follow the rules and wear makeup and heels to auditions. But trying to look sexy for TV executives when I don’t even know what sexy feels like makes me want to cry and vomit and murder. You can see this struggle in my expression whenever my mom takes a photo of me in outfits we hope will get me a job. (They don’t.)

I need to gain some control, so I pivot. Instead of pretending to fit in at school, I stay home alone pretending to understand “Mulholland Drive.” I swap Cecily Von Ziegesar for Albert Camus and get into ironic comedy. You can’t hurt me. I’m highbrow now.

This experience has not deluded me about the show’s quality; its purpose, at best, is to tantalize common people with glamour and riches, like “The Great Gatsby” of this coming generation, just substituting superfluous sex scandals for meticulous symbolism. Still, during commercial breaks in the pilot’s airing, I was not poised or satisfied that I was not part of the unfolding mindless mania. I was and am distressed because I want the show to give at least one reminder to its impressionable viewers that it’s mere entertainment, not something to which they should aspire. The CW got its Lolita. I get text messages with links to mean celebrity gossip sites and “Gossip Girl” gets viewers searching for role models. With this rejection comes both the bitterness toward this Jenny’s unrealistic effect on girls’ perceptions and also the determination to always have the opposite.

I’d always remembered this essay as Teenage Sarah overcompensating for professional disappointment by rebranding herself from “Mary-Kate and Ashley Fan” to “Intellectual Who References ‘The Great Gatsby.’” I was shocked to realize I might have obsessed so much about “Gossip Girl” because it was actually easier to accept than my uncle doing so many drugs his heart stopped working. I could cosplay as “Artiste Who’d Always Hated The CW Anyway.” “Teen Dealing With Addiction & Intergenerational Trauma in a Healthy Way” was out of my grasp.

I wish I could tell Teenage Sarah: “What you could still feel on the elliptical a.k.a. that ‘really tight feeling inside my chest’ a.k.a. GRIEF is human, natural, painful and scary. You cannot escape it no matter which job hires you, which guy likes you, which college accepts you, what you look like or what type of media you base your identity on. You can’t numb the bad feelings without cutting off the good ones too. You can either face your feelings now or carry them around for 14 years until one day you find yourself piecing together old essays, emails and diary entries without knowing why.”

I’m grateful to finally see the truth but I’d be lying if I didn’t say a part of me, when I put it all together, wasn’t like, “Maybe I should just call off this article and never tell anyone so they don’t think I’m a freak.”

Then I remembered that what I learned from my family — to not talk about the pain — doesn’t work for me. Neither does pretending to be above it all. Actually, in addiction recovery, they live by the exact opposite idea: You’re only as sick as your secrets.