Ross May / Los Angeles Times; photo by Ryan Chen

- Share via

I press play, and the voice of my waipo, my maternal grandmother, comes tumbling out of my computer’s speaker; it sounds like she’s in the room with me.

“I came to Tainan when I was 18 years old. Now I’m 75 years old,” my waipo says.

A long and drawn-out silence. The sound of her eating. I scrub through the recording. “What did your mom cook for you?” I hear my own voice, shrill and awkward, trying to fill in the gaps.

“I don’t remember. Back then it was tough. When I was a kid, we just ate everything.”

“What was it like when the Nationalist government came from China and took over Taiwan?”

“I don’t know. I have never paid attention to politics.”

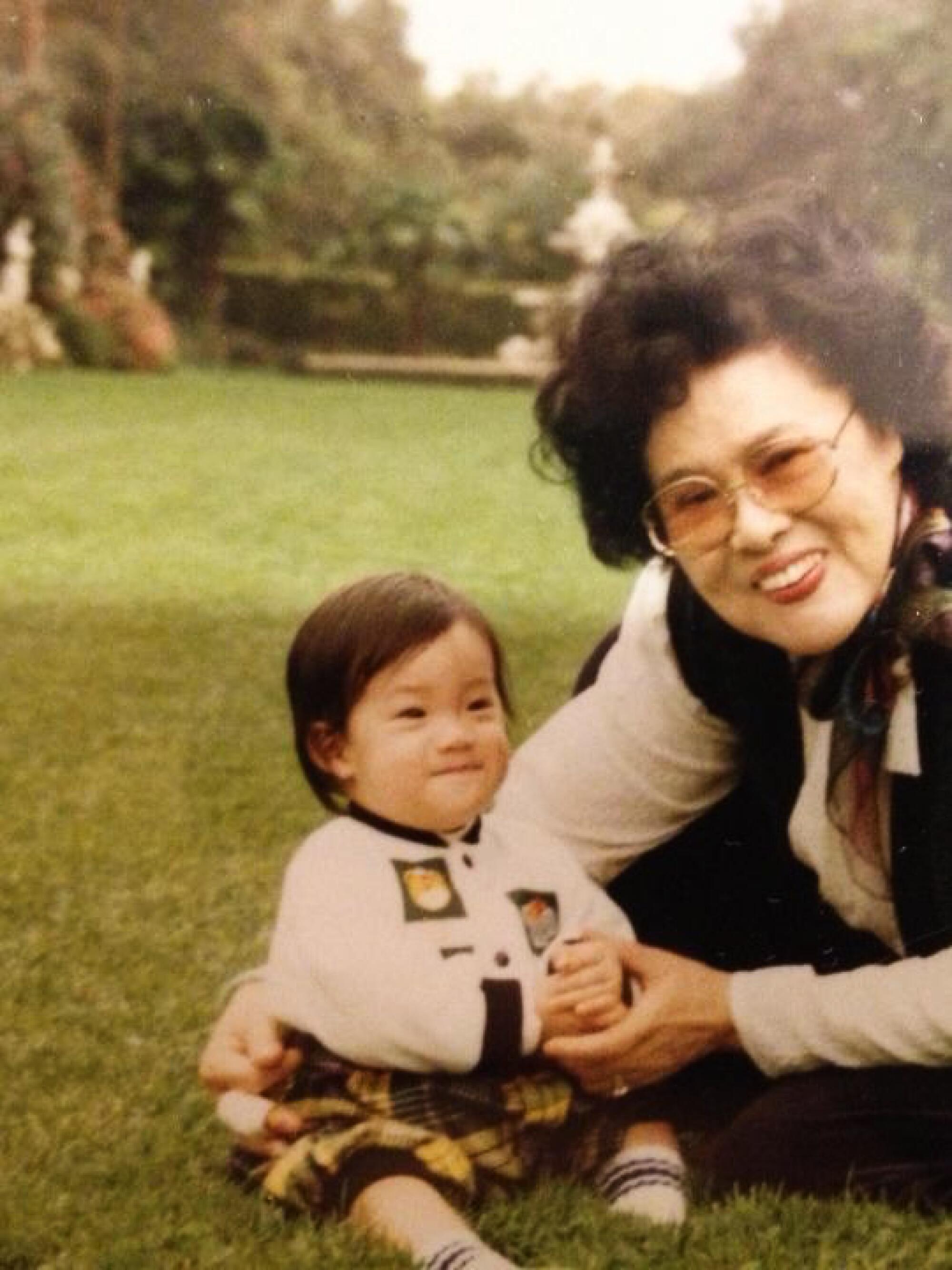

I can count the number of interactions I’ve had with my waipo on two hands. Several times when I was a kid visiting Taiwan from California, once on a family vacation to China a couple years back, and the most recent two times at her home in southern Taiwan when I was recording her and her recipe for zongzi — a pyramid-shaped rice dumpling wrapped in bamboo leaves — for my upcoming cookbook on Taiwanese cuisine.

I haven’t seen her since.

All my interactions with her had been stilted and klutzy, in part because my family never had much of a relationship with her. My grandmother was in her early 20s when she was forced to give up her children — my mother and my aunt — to her ex-husband’s family as a condition for divorce. He was an absent and terrible husband; she did not want to live her young life on his terms. But because his parents were rich, they had leverage, and my waipo was quickly cast out of her own daughters’ lives. My mom was raised by her paternal grandparents — wealthy doctors who spoke fluent Japanese, Hokkien and Mandarin and owned their own clinic. Trilingualism was a mark of affluence in their era. By contrast, my waipo was a barber and cut people’s hair for a living. She mostly spoke Hokkien and only learned Mandarin later in life.

“When your mom was at school, I’d wait outside to give her candy,” she says with sadness. Her voice gets louder as I edge the recorder closer to her. “But they wouldn’t let me see her for long.”

From comedy to art to film, you can celebrate Asian Pacific American Heritage Month in Los Angeles with these fun events.

This 25-minute-long recording of my conversation with my waipo now lives in my external hard drive, mostly populated with mundane small talk and long silences. I was recording her voice under the guise of work — I wanted her recipe and backstory for my book — but really, I was doing it for posterity’s sake.

When I left her house after my interview with her, I made a note to myself to go and visit her more often. And over the next couple of days, she began to send me a flood of photos and videos of her cooking that her partner had taken of her. Her standing over the stove, browning pork belly in a large, rusty brown carbon steel wok, a ceramic mustard-yellow jar of lard, with pink flower flourishes, by her side. Her sitting at a table, cutting up a pile of vibrant purple shallots. Her holding up a fresh slab of pork belly, proud and beaming at the camera. Although she did not express it outright, I could tell she was glad to have connected with me.

Soon, the messages stopped. A couple months after my conversation with her, she died.

It was an aggressive cancer that had started in her liver and eventually engulfed her whole body. I could not make it to the hospital because of COVID-19 restrictions. I did not go to the funeral because no one told me about it.

“I regret not asking more questions. I regret not visiting again before it was too late.”

Replaying her voice and our conversation together remains an extremely uncomfortable experience, not because of its contents but because it is a visceral reminder of the first, last and only real connection I had with her. I regret not asking more questions. I regret not visiting again before it was too late.

As a journalist, I have spent many hours in front of other people’s grandparents recording their stories for work. Usually the offspring are there with me and express a fascination at all the previously untold and hidden stories that come tumbling out of their elders when the right questions are asked.

This was the first time I had recorded my own.

“What did your parents do for work?” I hear myself asking my waipo.

“They owned a rice factory,” she says.

“Did you help?”

“Yeah.”

“Did you grow rice?” I was excited at this moment; I had spent the last year researching rice for my book and had no idea anyone in my family knew anything about it.

“No. We didn’t grow it. They took in the rice and processed it.”

“What types?”

“All types.”

Although blood ties are not a prerequisite for family, and although we ourselves are responsible for shaping and creating our own destinies, it is a moving experience nonetheless to hear about our lineage directly from our ancestors, no matter how distant, estranged or fraught the relationship is. Because whether we like it or not, the decisions they made in their lives — however mundane or insignificant — have had a direct impact on our existence.

Because of this, over the years I’ve made a more conscious effort to get to know my family history despite my parents’ apathy toward their past. From the little that I’ve gleaned, I know that I am descended from a pair of stubborn, single Taiwanese mothers. Both my maternal and paternal grandmothers were impoverished, uneducated women who grew up at the cusp of a regime change in Taiwan, when the island was handed over from Japan to the Republic of China. They spent the majority of their youth under martial law. They saw Taiwan transition from an impoverished war-torn country to an East Asia economic powerhouse.

When my waipo first learned how to cut hair as a teenager, her starting salary was just $1 a month. When she was 18, a charismatic, handsome young man came to her salon to get his hair cut. They got to know each other; she fell pregnant with his child. That child turned out to be my mom. If he did not go into her barbershop, if she did not meet him, I would not exist.

“Your aunt reminds me of him,” her voice says in the recording. “Bad temper.”

A couple of neighborhoods away in the same city, my paternal grandmother was single-handedly responsible for raising five young children. To make ends meet, she operated a secret beauty clinic on the upper floor of her house, where she’d administer cosmetic injectables to rich housewives and eventually saved enough money to send her children — my father and his siblings — to the United States to live. I also interviewed her before she died a couple of years ago, but back then I lacked the foresight to record her voice. “We were so poor we could not afford shoes. We had to borrow shoes,” she had told me. “Most schoolchildren did not have shoes.”

If she did not open that secret beauty clinic and make as much money as she did, I would not have been born in America. I would not be writing in English.

These two women, with all their flaws and strengths, are the reason I’m here, along with a constellation of other ancestors whose stories I’ll never know or hear.

I grew up with my paternal grandmother and have years of memories, photos and videos of her. Unfortunately, I did not have that luxury with my maternal grandmother. Instead, I have her recipe and this audio recording — a digital replica of her voice that might outlast even me. Although it is not a replacement for a lifetime of memories, it is a priceless heirloom nonetheless.

So the next time you see your grandparents or aging loved ones, take out your phone recorder. In a world where almost everything can be recorded, documented and photographed instantaneously, sometimes we forget to record the very people and noises we take for granted because we assume we’ll always have more time.

Do marijuana and motherhood mix? ‘Cannamoms’ share their experiences with stigma, stress and pot parenting.

When my waipo passed away, I asked my relatives if I could keep her rusty large wok and the mustard-yellow jar of lard. She had shown me how to make zongzi with these tools, though when I had asked her about them, she didn’t find them extraordinary at all.

Despite cooking with the wok for over 20 years, I don’t think she ever learned how to properly season it. As its new owner, I scrubbed it clean and reseasoned it and baptized it over high flames to give it life. Glistening and with a brand-new patina, it now sits behind me in my apartment in Taipei, nestled on the shelf above her ceramic lard jar as the audio recording of her voice plays on my speakers — her sound waves bouncing off the same objects that were there with us when I first made the recording, a physical and auditory snippet of her life that I will pass down through the generations.

Clarissa Wei is a freelance journalist based in Taipei. Born in Los Angeles but raised on the food of Taiwan, she is currently writing her first cookbook, Made in Taiwan (Simon Element), due out in fall 2023.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.