Editorial: Bring back the lost children of Los Angeles Unified

- Share via

Some 10,000 to 20,000 Los Angeles area kids are missing — not in the picture-on-a-milk-carton sense, but vanished from Los Angeles Unified School District enrollment rosters and unaccounted for as schools plan the start of classes on Aug. 15. It’s hard to determine exactly where they are.

The district’s enrollment appears to be down by about 80,000 since fall of 2019, shortly before the COVID-19 pandemic, to this fall. Many students switched to charter schools or other school districts or moved out of state. Others were home-schooled as a response to the pandemic and remote learning, and parents haven’t filed their paperwork with the district. And enrollment was always expected to drop, as it has for years, because of demographic shifts. There are now close to 400,000 students, a huge diminishment from the nearly 750,000 or so LAUSD had 20 years ago.

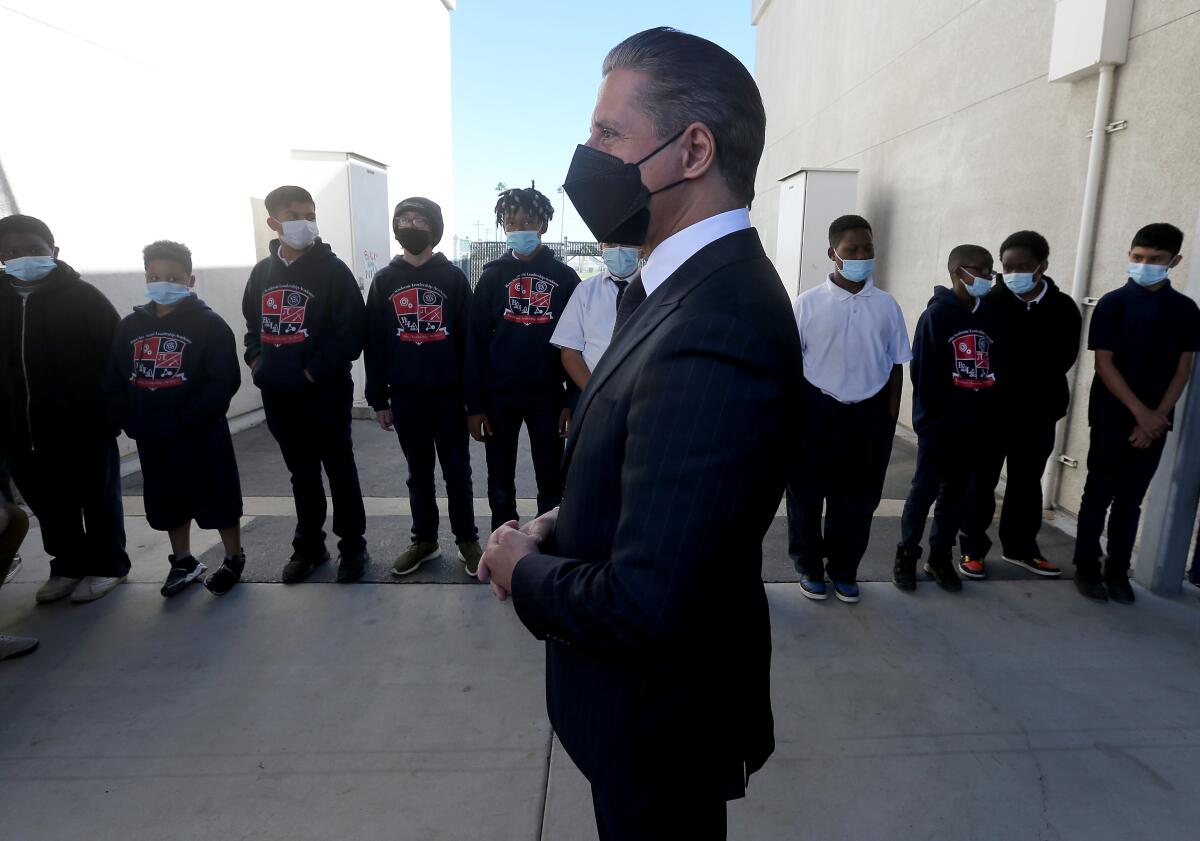

But Supt. Alberto Carvalho says that even after accounting for the transfers and demographic changes, the numbers aren’t adding up. There still are those 10,000-plus lost kids out there. They’re concentrated in the earliest grades and in high school, he said.

The school district is dropping toward 400,000 students. There aren’t enough teachers, counselors or nurses for hire. It’s time to envision a smaller school district.

The district has attempted to understand why there are so many unenrolled kids. Carvalho said parents who are home-schooling might be late filing their paperwork with the district. Others might have moved out of state without notifying the district. But the district has also discovered deeper problems.

By contacting a sampling of the families, officials found that some students are working and taking care of younger siblings, especially in homes where the parents might have personal and health issues that result in their not supporting their families, Carvalho said. At the younger end, from transitional kindergarten through first grade, he said some very new immigrants appear not to realize that they have to enroll their children. They’re unfamiliar with the education system, wary of public officials, and may not understand that if they wait until a child is age 7 or older, the child already is almost hopelessly behind. For younger and older kids, just getting to school is a problem without transportation.

It’s easy to complain about parents and say there’s nothing to be done if they don’t get on board. But that’s not only unproductive, it’s unfair. These kids didn’t ask for their situations. They deserve a decent start in life, and some of the teens are taking on responsibilities that would swamp the average adult.

LAUSD has a history of not following through with its grand plans, such as the goal to help students make up pandemic learning loss with ‘high-dosage’ tutoring.

Where possible, the district needs to get kids into school. That starts with something as simple as school buses. In New York state, transportation is covered even when students attend private school. California needs to step up its game. In L.A. Unified, most students have to live at least five miles from their school to qualify for busing. This year the state budget will add more than $600 million for school busing. Though it will be a big boost, it’s not enough to transport all the students in the state who need a ride. L.A. Unified must do what it can to fund more buses, and find bus drivers, who are in short supply.

To get the youngest students started on their education, the district plans an enrollment campaign in immigrant communities, where significant numbers of families don’t speak Spanish but rather regional languages.

But at the high school level, the district needs more drastic action. That includes beefing up vocational education programs that can help graduates immediately earn at least twice as much as the minimum wage, and that’s a value working teens can appreciate right now. With a diploma and more financial stability, they might decide in the future to start college to better their futures. But if the district doesn’t make substantial efforts to bring older students back by offering the kinds of classes they want, these students will have neither a decently paid career nor much possibility of college.

L.A. Unified is already planning a more organized and robust remote education program for 2022-23, with several specialized “academies.” But the program is not heavy on vocational education and a significant portion isn’t flexible enough to meet the needs of teens who need to work right now. The district should be assuring teens that it will meet their scheduling requirements and give them the options they need to graduate. That won’t be easy, but it’s crucial.

Carvalho says he’ll unveil plans this week for more vocational education and independent study. If L.A. Unified is willing to invest the money and expertise, these programs could be the answer not just to recapturing the current lost kids of L.A., but engaging future students in studies that will prove relevant and rewarding.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.