Opinion: Here’s what celebrations of Juneteenth shouldn’t be missing

- Share via

America has reached the third anniversary of Juneteenth becoming a federally recognized holiday, after a tough first two years. In 2021, with Americans on high alert over COVID-19, many celebrations were limited to Zoom. Last year, companies drew controversy for Juneteenth merchandise, including products with perplexing use of slogans in African American English such as “It’s the freedom for me” and Walmart’s poorly received and reportedly appropriated Juneteenth ice cream.

What’s most needed to celebrate Juneteenth is a history lesson. Instead, people including Donald Trump and Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis have led the charge to diminish African American history in public education. Toward the end of Trump’s presidency, his administration pushed propagandistic “patriotic” education to minimize slavery’s legacy. Under DeSantis, Florida’s government has restricted how race is taught in schools.

It is impossible to celebrate a national holiday that marks the emancipation of Black people in Galveston, Texas, on June 19, 1865, without confronting the history of slavery and the role of education in freedom.

What is Juneteenth and who helped make it a federal holiday? When did the last enslaved people in the United States learn they were free?

Educating Black people, women and poor communities has historically been a direct threat to white supremacy. After the Stono Rebellion failed in South Carolina, state officials created the Slave Code of 1740. Enslaved people were forbidden from earning a living, growing their own food, assembling in groups, moving about freely or learning to read or write, tethering literacy to criminality. An enslaved person could be violently harmed for attempting to read and even sold away from their families.

Other colonies followed South Carolina’s example, even up North. In 1835, George Kimball, a white abolitionist, created the interracial Noyes Academy in Canaan, N.H. The first class had 28 white students and 14 Black students. Outraged by integrated learning, a 300-resident mob wrapped chains around the school and pledged to “drag the n— school off its foundation and through town.” They did, using more than 90 oxen to drag the school into the river. Some of them set the building’s remnants on fire — a reminder that although the North continues to look down on the South as backward, its residents can’t quite sit on a moral high horse.

When the Civil War ended and slavery was abolished, one of the first things formerly enslaved people sought, in addition to family members and land ownership, was an education. A great benefit of Reconstruction was the universal public school system established during the 1860s.

Northerners sent teachers akin to missionaries to the South with the goal of educating formerly enslaved people. Those teachers included Black abolitionist Charlotte Forten Grimke, who traveled from Philadelphia to South Carolina’s Sea Islands to teach newly freed African Americans at the Penn School. Grimke declared, “The long, dark night of the Past, with all its sorrows and its fears, was forgotten; and for the Future — the eyes of these freed children see no clouds in it. It is full of sunlight, they think, and they trust in it, perfectly.” Grimke identified the hope that came with education, the promise that the future of freedom could finally take any form Black children imagined for themselves.

Decades of crucial work by Black researchers get left out of the American story when “historians” are classified solely by their degrees.

Two things happened incredibly fast in this period. First, Black people used their liberation to advance the country. Within a few years, formerly enslaved individuals became elected officials; over 1,500 Black men served in office during Reconstruction. For the first time Black people had freedom, citizenship, voting rights — and political influence. Second, the white backlash to Black progress was immediate.

Restrictions on Black freedom were revived via the Black Codes as early as 1865. Not long after, General Nathan Bedford Forrest created the Ku Klux Klan in Tennessee. The terror the Klan inflicted on Black communities compelled President Ulysses S. Grant to enact the Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871, outlawing the group’s violence and political intimidation. But the law was not enough to stop the country’s regression.

This is part of America’s legacy, and efforts to ban books or remove state funding for diversity, equity and inclusion cannot change the truth. Policies to marginalize and erase Black history also weaken our democracy by diminishing freedom, replicating the anti-education ideology employed during slavery.

Summer has a way of reminding the nation what is at stake. The season’s federal holidays — Memorial Day, Juneteenth, the Fourth of July and Labor Day — call us to remember fallen soldiers, the last enslaved people to gain emancipation, the birth of a nation, and our county’s reliance on laborers.

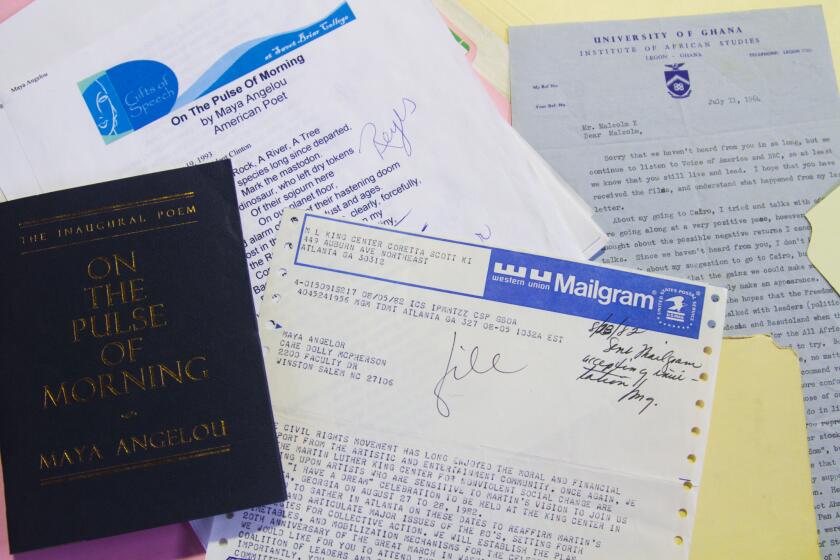

For Juneteenth, we should also remember that Black communities’ celebrations include dreams and delight. At Emancipation Day gatherings, nothing has given Black families more pride than their children standing up to read a proclamation, poem or scripture that affirmed their humanity. Older community members might offer up their testimony on what it has meant to survive and be free — to live lives completely antithetical to slavery, controlling your own personhood, mobility and education.

The more politicians and parents stray from these ideals by limiting what students can learn, the further backward we go in a direction reminiscent of slavery.

Kellie Carter Jackson is an associate professor of Africana Studies at Wellesley College and the award-winning author of “Force and Freedom: Black Abolitionists and the Politics of Violence.” @kcarterjackson

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.