San Francisco’s Presidio faces challenges over development

- Share via

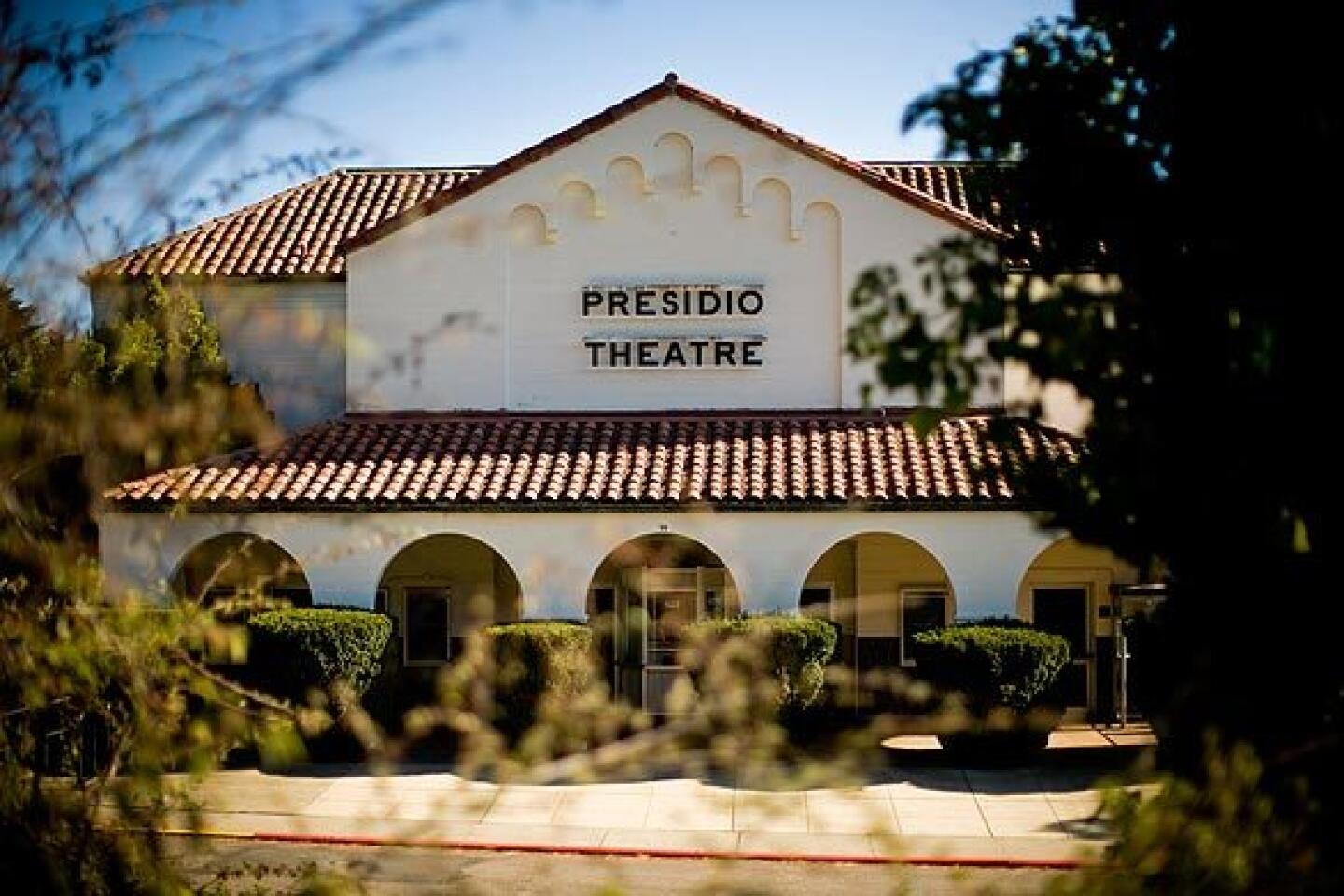

SAN FRANCISCO — Even in a city where public meetings can become a contact sport, few places generate as much passion as the Presidio, site of the city’s birthplace and one of its most beloved public spaces.

So there was little surprise when public outrage erupted after the trust that operates the sprawling former military post announced this year that it planned to build an upscale hotel and massive art museum at the heart of the Presidio.

The loud public bickering has underscored a predicament for the Presidio, which was transferred to the national park system in 1994 with a mandate that it be financially self-sufficient by 2012.

Getting there has required an uncommon commercialization plan that discomfits those who prefer their national parks without the branding. It means that history buffs who stroll among the Presidio’s grand buildings also pass coffee shops, yoga studios and other storefronts.

Although most people have adjusted to the commercial hum in the background, the question now is how far is too far, and whether self-sufficiency requires bowing to influential philanthropists and private development companies.

At issue is a plan to transform the Main Post -- a blend of 19th-century buildings and twin parade grounds that sit on a rise -- so it sweeps down to the foot of the Golden Gate Bridge. The former officers’ club and barracks were once the busy hub of the Army’s 150-year presence here. A grassy parade ground long since gave way to an asphalt parking lot, nearly empty on most days.

Few argue with plans that would bring the grass back and “re-animate” the post. But critics say four of the five alternative proposals are little more than show. The Presidio Trust, they say, is trying to railroad through a 100,000-square-foot contemporary art museum and a 95,000-square-foot hotel. A host of smaller projects are included in the plan.

The debate has been public and acrimonious. The fire marshal was called when more than 700 people crowded into an overflowing public meeting in July, where Mayor Gavin Newsom was roundly booed for supporting the project. For six hours, the trust’s board members listened to a parade of citizens excoriating the favored proposal as “an insult to the Main Post” and telling them “you will suffocate history.”

Another speaker, a retired attorney, echoed what many others said that night, suggesting that because a wealthy and influential couple were behind the proposed museum, “the fix was in.”

“This whole process seems to me to have an inevitability about it,” said Robert Laws, who attended the meeting and identified himself as a lifelong San Franciscan. “I don’t wish to be offensive, but I must be frank. Externally, it has the appearance of something that’s going to happen no matter what. I see this whole process marching to a courtroom and legally over a cliff.”

Craig Middleton, the trust’s executive director, is accustomed to great scrutiny over Presidio projects, but noted dryly, “There has been a particular vehemence to the opposition.” Regarding charges that the planning process has been less than transparent, Middleton said, “I can guarantee you that the fix is not in. I know there is a lot of that feeling in the public.”

The Contemporary Art Museum at the Presidio is the pet project of Don and Doris Fisher, the billionaire founders of the San Francisco-based Gap stores. The Fishers approached the Presidio Trust a year ago and offered to build a museum to house their world-class collection of modern art.

The trust’s plans had always included a museum. But members thought such a large structure would be sited less ostentatiously at the bottom of the hill from the Main Post, near Crissy Field, where it also would be close to public transportation.

The Fishers have made it clear that they want their building to sit on the promontory at the top of the parade ground, and those familiar with the negotiations said there is a chance that if the museum’s site, size and design are not approved, the Fishers would retract their offer.

“What started almost a year ago as a generous gift has become a flash point,” said Amy Meyer, a former board member who opposes the Main Post site for the museum.

“Essentially, the parade ground will become the front lawn for his museum. That is utterly unacceptable,” she said. “We’re dealing with someone who doesn’t want to bend. He wants the center stage. He can’t have it.”

Don Fisher, through a spokesman, declined to be interviewed for this story.

The trust is in the unenviable position of wanting to accept the Fishers’ gift but to keep it from derailing the planning process and degrading the Presidio’s historic integrity.

“My perspective is that we have an incredible opportunity that doesn’t come along very often,” Middleton said. “Does he get the final word? In some respects he does; in some respects he doesn’t. It’s really a dance. Our responsibility is not to create a museum at the Presidio. Our responsibility is to take care of the Presidio for the American public. If it turns out that having that building in that spot is the only way we can go, and we determine that it’s not good for the Presidio, we won’t go forward.”

Already, two usually sober agencies, the National Park Service and the National Trust for Historic Preservation, have told the trust that the project could cause the Presidio to lose its cherished status as a National Historic Landmark District. Such a de-listing rarely occurs, more often than not after a natural disaster damages or destroys a site.

In a letter to the trust, California’s Historic Preservation Officer described the museum as so “radically out of place in terms of design, materials and scale that it is difficult to imagine how it could be made to conform to its setting.”

And the trust’s own federal preservation officer wrote in a report that the museum plan would cause 10 “adverse effects” to the Main Post’s historic sites.

The trust did not release the document in time for public debate over the location. Then, the report was systematically toned down through 16 drafts, prompting the resignation of the historian who prepared the analysis.

The Presidio, established as a military post by the Spanish in 1776, was used as a base for the Army from 1848 until 1994. The post then became part of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area, operated by the National Park Service.

Some say damage has been done to the trust’s reputation as steward for the Presidio.

“They are kind of setting themselves up for failure,” said Neal Desai of the National Parks Conservation Assn., a parks advocacy group that generally maintains friendly relations with the trust.

“The longer-term problem is they are called the Presidio Trust, but they are going to move down the path to lose the public trust,” he said. “You are compromising goodwill here.”

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.